Luigiemanuele Amabile in conversation with Niall McLaughlin.

What distance, or what proximity, exists between the tangible conditions that architecture must address and the possibilities for speculation within a design studio? This question forms the basis of the interview with Níall McLaughlin, which explores the ways in which a project emerges at the intersection of materials, techniques, social expectations and imaginative possibilities. At the same time, it considers the relationship between professional practice, which is characterised by constraints, responsibilities and tight deadlines, and the academic studio, where one can broaden their perspective and explore hypotheses that have not yet found a place in everyday work. McLaughlin presents these two spheres as interdependent parts of a single formation process, in which technical precision and speculative openness coexist to contribute to the development of a project-based community.

LA: In your opinion, how should a contemporary architectural design studio be structured in terms of its work over an academic semester and its day-to-day practices? Which tools should it prioritise? In particular, I am curious to know whether physical models, hand-drawn sketches, digital renderings, immersive simulations, data-driven parametric analyses, or some combination of these, should predominate. Could you illustrate your stance by describing concrete routines within your own practice and teaching, noting how each chosen medium either reveals or conceals specific dimensions of architectural enquiry?

NM: I certainly would not restrict myself to any single medium. Whatever one is using at a given moment – whether making a model, drawing by hand or working digitally – is simply a window through which the proposal is observed. Each window reveals some things and screens others. The aim of the studio is to sustain a constructive, critical conversation with every student about which medium he or she is employing and what is expected from it, so that no-one slips into the lazy habit of supposing that one medium will always do the same job. What matters is to cultivate an informed understanding of what each tool can offer at that precise stage of the project. Contemporary students – and indeed colleagues in my office – gravitate toward digital platforms, yet even there we continually move in and out of different techniques, asking ourselves what we are seeking and which instrument will serve the investigation best. While recognising the advantages of screen-based representation, I press back and remind everyone of the haptic, corporeal character of design: the eye, the mind and the hand operate in a feedback loop, so that drawing – especially drawing together – is as bodily as it is mental. The critical attitude, not a dogmatic preference, must govern our engagement with whatever media are at hand.

LA: Building upon this premise and considering the accelerating temporal, economic and regulatory pressures shaping contemporary practice, I would like to examine the issue of pace and depth in studio work. To what extent should slower, more contemplative modes of production, such as extended material model-making, iterative hand-sketching, lengthy peer critiques and other forms of deliberate reflection, be preserved and protected within the academic studio environment? Or should architectural pedagogy embrace the brisker tempo and data-rich workflows imposed by twenty-first-century professional life, thereby preparing students to work fluently within the constraints and deadlines they will face after graduation?

NM: One must reject the cliché that digital media inhibit reflection whereas analogue media guarantee it. Reflection depends on how we use a medium, not on the medium itself. In our office we move constantly between media but always in response to the question: “What are we trying to discover right now?”. The same conversation underpins our teaching. It is true that commercial, legal and temporal pressures leave little space for speculation in practice, which is why an office has to carve out such space deliberately. Designing together, for me, is a way of establishing a small society within the practice – a collegiate culture in which each member feels an intellectual, emotional and creative responsibility toward the others. We draw together in order to think, work and create together, thereby building the community our projects require. One cannot expect those benefits to arise passively; they must be planned for – just as one should model the relationship between education and practice so that each continually reinforces the other, rather than allowing an unhealthy separation to develop between “idealistic” education and “compromised” practice. Students begin being architects in the first year, and practising architects should continue educating themselves throughout their careers.

LA: Your remarks naturally invite a closer examination of the relationship between academic speculation and professional constraints. In light of the competing pedagogical philosophies – some of which advocate rigorous immersion in the pragmatic realities of legislation, budgeting, construction feasibility, and site-specificity, while others champion unbridled conceptual exploration – how far should the material exigencies of architecture, in your judgment, permeate the university studio? Conversely, to what extent should academic settings protect students from immediate economic or regulatory pressures, thus allowing for speculative freedoms that could subsequently enter practice as innovative paradigms?

NM: Posing the issue as though “reality” leaks into an otherwise sealed vessel – the studio – is itself misleading. The studio is already a form of reality, albeit one that ought to be examined critically for the ways in which it resembles and differs from other realities. In both education and practice an architect is continually required to acquire new skills, assimilate new knowledge and think flexibly and speculatively about new ways of operating, all the while remaining grounded in architecture’s vocation as a social-material practice. The unfortunate division that has arisen over the past half-century – whereby architectural education in universities is often recast as a branch of the humanities – obscures that vocation. I am not opposed to educating architects within universities, but I oppose the uncritical adoption of an academic template that fails to recognise architecture’s particular modes of teaching and learning.

LA: Even accepting that critique, might one nonetheless posit that the university studio affords a distinctive formation of freedoms – temporal, conceptual, ethical – less readily available within commercial practice? Or does your model of continuous dialogue between education and practice render such a dichotomy obsolete, implying that both realms should be understood instead as mutually corrective and mutually enriching arenas within a single lifelong process of architectural formation?

NM: In my model of continuity every stage of an architect’s life, whether as student or practitioner, offers distinct freedoms and imposes distinct obligations. The idea that university life is pure freedom and professional life pure obligation is a deeply unhealthy misconception. Education should produce work that challenges professional norms and values while simultaneously engaging with the realities that practitioners confront daily. I am equally critical of the notion that graduates should be “oven-ready” for practice and of the converse tendency for academia to alienate itself from practice; both extremes are counter-productive. Skills and values are interdependent – indeed inseparable – and both must be cultivated throughout one’s career.

LA: A recurring theme in your previous answers is the idea of the studio as a small, cooperative society, where drawing serves as both a cognitive tool and a social bond. Could you elaborate on how individual authorship is balanced against collective endeavour within that society, with reference to specific pedagogical exercises you have devised? In other words, how do you reconcile each student’s freedom to chart a unique intellectual and creative path with the need to participate empathetically, and even critically, in collaborative design?

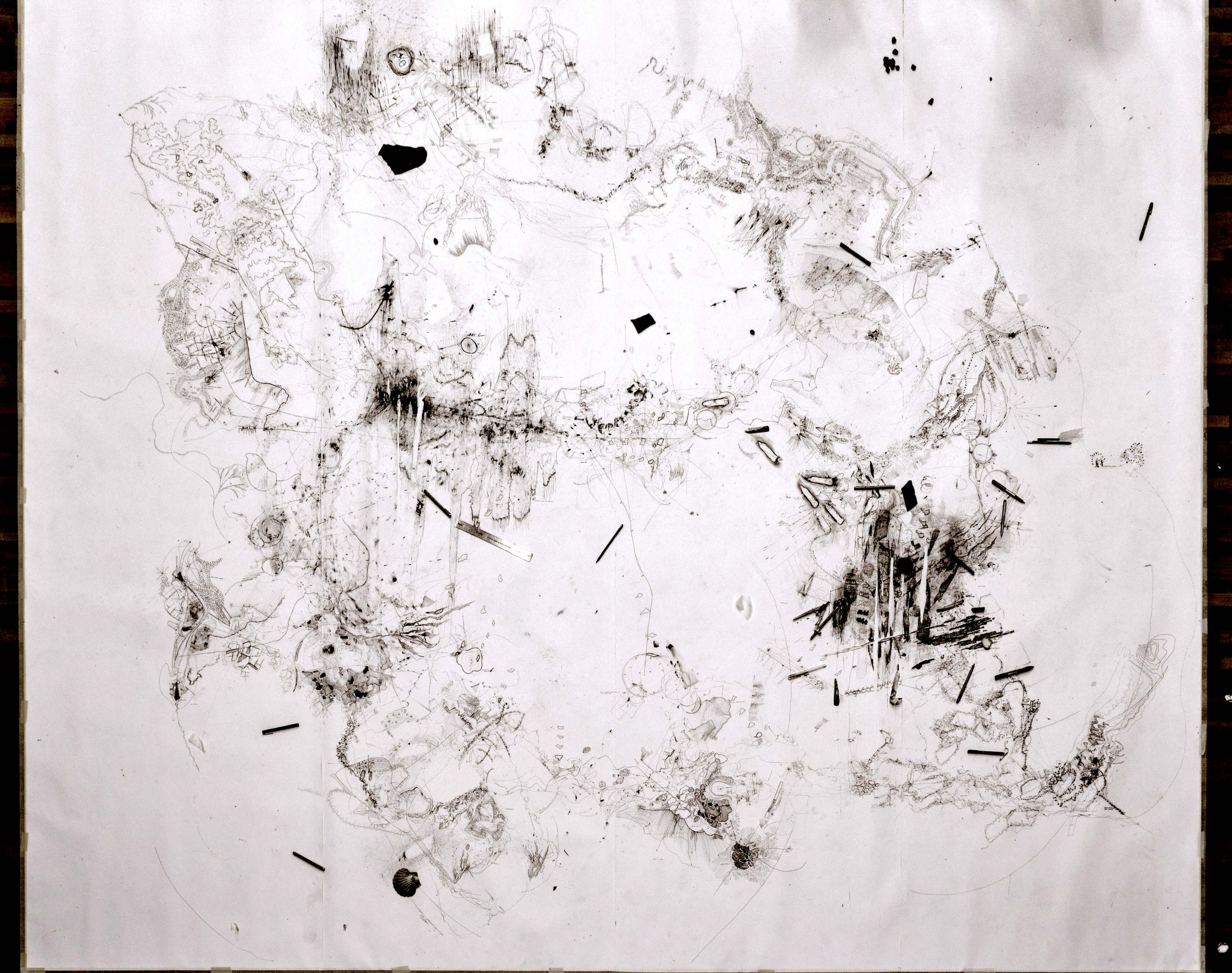

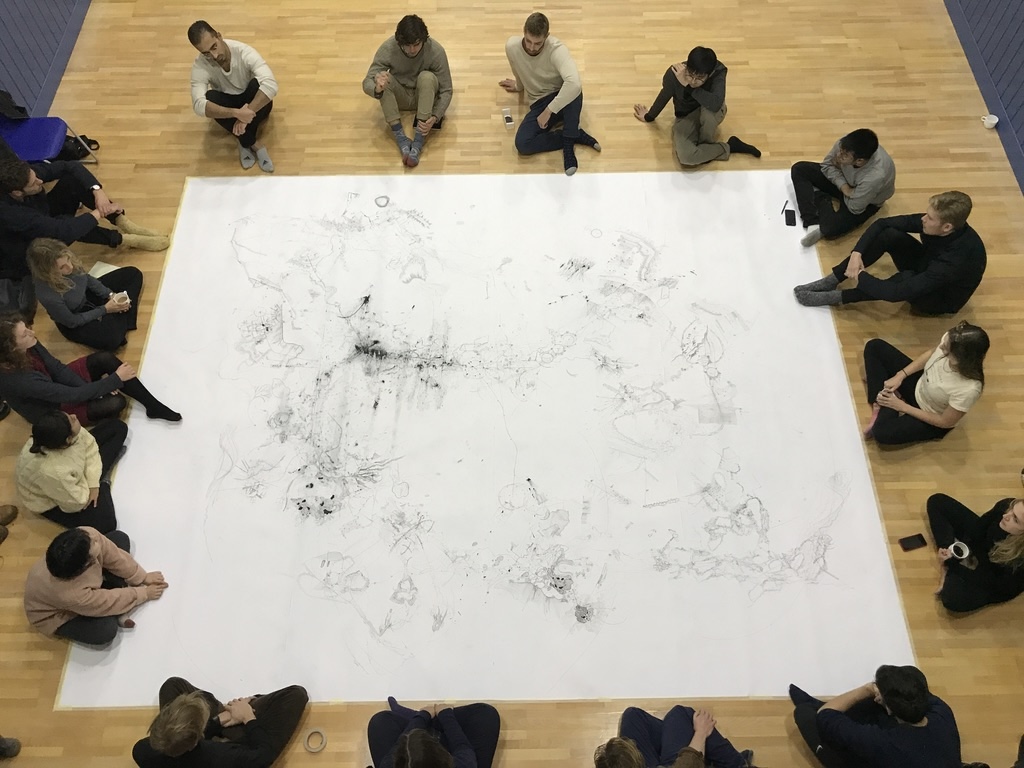

NM: Throughout my teaching career I have set collective projects whose primary purpose is to teach students to rely on one another. We may work with cohorts of sixteen or eighteen students; the opening exercise obliges them to communicate and depend upon one another, and if, at a certain point, they begin teaching each other, I half-jokingly say that I could sit back and smoke a cigar, because the enterprise has achieved its goal of mutual education. One such project, Drawing Together, developed with Yeoryia Manoloupoulou, with whom I taught Unit 17 at the Bartlett School of Architecture at University College London between 1999 and 2019, is documented in Jonathan Hill’s Designs on History: The Architect as a Physical Historian. In that workshop we walked an island every day and drew together every evening in an open, collaborative process; the experience rewired how the students perceived one another. Within any studio cohort every student is seeking an individual voice yet does so in the company of friends, colleagues, critics and competitors, with teachers conducting the ensemble. Ideally the hierarchy evolves into an ecosystem in which roles differ, but no-one is deprived of agency – rather like musicians improvising together. That, for me, is a good teaching studio.

LA: Within this ecosystem, the question arises as to whether it is more important to transmit concrete skills (drawing, model making, structural reasoning, specification writing) or to instil broader dispositions – critical curiosity, ethical judgement, collaborative empathy – towards architectural problems.

NM: I resist separating the two. As one acquires skills one simultaneously acquires values; to uphold those values with genuine integrity one must possess the requisite skills. I am particularly concerned with the architect’s authority within the construction process, for it is part of the architect’s duty to bind the project team together. Builders can read drawings like X-rays: they see what you know and what you do not. A good construction drawing tells them not only how the building will look but how it will be made and what problems might arise during assembly. If those matters have been thought through, the builder feels in safe hands. Such integrated skills ought to be taught to every architect, yet they are too often neglected.

______________________________________________________________________________________________

L’architettura come pratica sociale-materiale

Luigiemanuele Amabile in conversazione con Niall McLaughlin.

Quale distanza, o quale prossimità, esiste tra la concretezza delle condizioni di realtà che l’architettura si trova ad affrontare e la speculazione che può svilupparsi all’interno di un laboratorio? L’intervista a Níall McLaughlin prende forma attorno a questo interrogativo, seguendo il modo in cui il progetto si costruisce nell’incontro tra materiali, tecniche, aspettative sociali e possibilità immaginative. In parallelo emerge il rapporto fra la pratica professionale, segnata da vincoli, responsabilità e tempi serrati, e il laboratorio di progettazione, dove lo sguardo può dilatarsi e mettere alla prova ipotesi che ancora non trovano posto nel lavoro quotidiano. McLaughlin descrive questi due ambiti come parti interdipendenti di una stessa formazione, in cui precisione tecnica e apertura speculativa convivono e contribuiscono insieme alla costruzione di una comunità di progetto.

LA: In che modo dovrebbe essere strutturato oggi un laboratorio di progettazione? Qual è il rapporto tra l’organizzazione del lavoro lungo il semestre e le pratiche quotidiane che ne definiscono il funzionamento? Che strumenti utilizzare, e quali far prevalere tra modelli fisici, schizzi a mano, render digitali, simulazioni, analisi parametriche? E come questi, all’interno delle routine consolidate della tua pratica professionale e della tua attività didattica hanno rivelato, oppure occultato, dimensioni specifiche dell’investigazione architettonica?

NM: Nella mia pratica didattica e professionale non mi sono mai limitato a un solo medium, perché qualunque strumento utilizzato in uno specifico momento – che si tratti di un modello, di un disegno a mano o di un prodotto digitale – costituisce, in ogni caso, una finestra attraverso cui osserviamo la proposta di progetto. Una finestra che mette in luce alcuni aspetti ma che ne oscura inevitabilmente altri. Il punto essenziale del lavoro lungo il semestre laboratoriale consiste nel mantenere con ogni studente una conversazione critica, costruttiva, attraverso gli strumenti utilizzati e sulle aspettative che essi portano con sé, in modo da evitare che si formi l’illusione per cui si crede che uno stesso strumento assuma, ogni volta, la stessa funzione conoscitiva. Ciò che conta davvero è sviluppare una comprensione informata e consapevole di ciò che i mezzi disponibili all’architetto possono offrire rispetto alle specifiche fasi del progetto. Gli studenti più giovani, come del resto anche i miei colleghi, tendono naturalmente a preferire gli strumenti di produzione digitale. Ma anche in quegli ambienti ci muoviamo continuamente tra tecniche diverse, interrogandoci sugli obiettivi della nostra ricerca e su quale strumento possa sostenere al meglio l’indagine. Pur riconoscendo i vantaggi della rappresentazione su schermo, insisto spesso nel richiamare l’attenzione sul carattere aptico e corporeo del progetto di architettura, perché l’occhio, la mente e la mano operano sempre insieme in un circuito di reciproca influenza. Il disegno, soprattutto quando viene svolto collettivamente, è un’azione che opera sul piano sia fisico che mentale, e questa dimensione non può essere trascurata. È dunque una postura critica, e non una preferenza dogmatica per un particolare strumenti, a guidare il nostro rapporto con gli strumenti che abbiamo a disposizione.

LA: Considerate le pressioni economiche e normative e le continue emergenze che caratterizzano la pratica professionale odierna, fino a che punto è opportuno mantenere e tutelare all’interno del laboratorio universitario modalità di lavoro più lente e riflessive? Ad esempio, la costruzione di modelli, lo schizzo, le revisioni collettive e altre forme di riflessione e discussione? Oppure la didattica dell’architettura dovrebbe adeguarsi al ritmo più serrato e ai flussi di lavoro imposti dalla professione contemporanea, preparando gli studenti ad affrontare con naturalezza i vincoli e le restrizioni che incontreranno dopo la laurea?

NM: A mio avviso, è necessario respingere l’idea secondo cui gli strumenti digitali ostacolerebbero la riflessione, mentre quelli analogici la favorirebbero. La riflessione, infatti, non dipende dallo strumento in sé, ma dal modo in cui lo si utilizza. Nel mio ufficio passiamo continuamente da uno strumento all’altro e la scelta dipende sempre dalla domanda che ci poniamo in quel momento, ovvero da ciò che stiamo cercando di scoprire e capire. La stessa impostazione guida il mio modo di insegnare. È vero che le pressioni commerciali, normative ed emergenziali della pratica professionale riducono lo spazio per la speculazione, ed è proprio per questo che un ufficio deve ritagliarsi intenzionalmente tale spazio. Per me, progettare insieme significa costruire, all’interno della pratica professionale, una piccola società, una cultura collegiale in cui ciascuno si sente responsabile, dal punto di vista intellettuale, emotivo e creativo, nei confronti degli altri membri del gruppo. Disegnare insieme significa pensare insieme, lavorare insieme e creare insieme, dando forma alla comunità che ogni progetto richiede. Nulla di tutto ciò accade spontaneamente: questo processo va progettato con attenzione, così come va progettata la relazione tra insegnamento e pratica professionale, affinché si rafforzino a vicenda. È dannoso alimentare una frattura tra una formazione percepita come idealistica e una pratica percepita come compromessa. Gli studenti iniziano a essere architetti già dal primo anno e gli architetti praticanti devono continuare a formarsi per tutta la vita professionale.

LA: Restiamo sul rapporto tra speculazione accademica e vincoli derivanti dalla realtà. Alla luce delle molteplici modalità con cui si insegna il progetto, notiamo che alcune sono orientate a un’immersione rigorosa nelle realtà pragmatiche della legislazione, dei budget, della fattibilità costruttiva e della specificità dei siti, mentre altre sono rivolte a un’esplorazione concettuale più libera. Secondo te, fino a che punto le esigenze concrete dell’architettura dovrebbero permeare il laboratorio di progettazione? Inoltre, in che misura l’ambiente accademico dovrebbe proteggere gli studenti dalle pressioni economiche e normative immediate, consentendo forme di speculazione che potrebbero poi entrare a far parte della pratica professionale sotto forma di paradigmi innovativi?

NM: Formulare la questione come se la “realtà” filtrasse dentro un contenitore altrimenti sigillato, il laboratorio, è già fuorviante. Il laboratorio è infatti una forma di realtà che richiede però di essere esaminata criticamente per capire in che modo assomigli o differisca da altre realtà. Nella formazione e nella pratica, un architetto è continuamente chiamato ad acquisire nuove competenze, ad assimilare nuovi saperi e a pensare in modo flessibile e speculativo su possibili nuove modalità operative, rimanendo però ancorato alla vocazione dell’architettura come pratica sociale e con ricadute materiali. La divisione che si è prodotta negli ultimi cinquant’anni, piuttosto infelice, per cui l’educazione architettonica nelle università è stata spesso ripensata come una branca delle discipline umanistiche, oscura questa sua natura. Non sono contrario alla formazione degli architetti all’interno delle università, ma mi oppongo all’adozione acritica di un modello accademico che non riconosce le modalità di insegnamento e apprendimento proprie dell’architettura.

LA: Ammessi i limiti imposti dalla distinzione che hai appena criticato, si può comunque sostenere che il laboratorio di progettazione offra un insieme di libertà – temporali, concettuali ed etiche – difficilmente reperibili nella pratica professionale? Oppure il modello di continuità che proponi tra formazione ed esercizio rende irrilevante questa dicotomia, suggerendo che entrambi gli ambiti debbano essere intesi come spazi reciprocamente correttivi e complementari all’interno di un unico percorso formativo che accompagna l’architetto per tutta la vita?

NM: Nel modello di continuità che ho descritto, ogni fase della vita di un architetto, sia da studente che da professionista, offre libertà specifiche e impone obblighi specifici. L’idea che la vita universitaria sia associata esclusivamente alla libertà e quella professionale esclusivamente all’obbligo è un fraintendimento dannoso. La formazione dovrebbe produrre lavori capaci di mettere in discussione norme e valori professionali, ma anche di confrontarsi con le realtà che i progettisti affrontano quotidianamente. Sono critico sia verso l’idea che i laureati debbano essere immediatamente “pronti all’uso” nel mondo del lavoro, sia verso la tendenza opposta dell’accademia a isolarsi dalla pratica professionale, perché entrambi gli estremi sono controproducenti. Competenze e valori sono interdipendenti e, anzi, inseparabili, e devono essere coltivati lungo l’intero arco della carriera.

LA: Nelle tue risposte ricorre l’idea del laboratorio come una comunità in vitro, in cui il progetto funziona sia come strumento cognitivo sia come legame sociale. In questo contesto, come si bilancia l’autorialità individuale con l’impegno collettivo? Come hai sperimentato questa tensione negli esercizi di progetto? Pensi sia possibile conciliare la libertà di ciascuno di seguire un proprio percorso intellettuale e creativo con la necessità di partecipare in modo empatico e critico a un processo di progettazione condiviso?

NM: Nel corso della mia attività didattica, ho spesso proposto progetti collettivi pensati per insegnare agli studenti a fare affidamento gli uni sugli altri. Quando lavoro con gruppi di sedici o diciotto studenti, l’esercizio iniziale li costringe a comunicare e a dipendere gli uni dagli altri. Spesso, iniziano a darsi lezioni a vicenda e io scherzosamente dico che potrei sedermi e fumare un sigaro, perché l’obiettivo dell’impresa, ovvero l’educazione reciproca, è stato raggiunto. Un esempio è il progetto Drawing Together, sviluppato con Yeoryia Manoloupoulou e presentato nel volume di Jonathan Hill, Designs on History: The Architect as a Physical Historian, in cui ho insegnato la Unit 17 alla Bartlett School of Architecture dell’University College London dal 1999 al 2019. In quel workshop, abbiamo esplorato un’isola diversa ogni giorno e abbiamo disegnato insieme ogni sera, in un processo aperto e collaborativo che ha trasformato il modo in cui gli studenti percepivano gli altri membri del gruppo. In ogni coorte del laboratorio, ogni studente cerca la propria autonomia espressiva, ma lo fa sempre in compagnia di amici, colleghi, critici e concorrenti, con i docenti che guidano il processo. L’assetto ideale è un ecosistema in cui i ruoli sono diversi, ma nessuno è privato della propria agency, in una dinamica simile a quella dei musicisti che improvvisano insieme. Per me, questo è ciò che definisce un buon laboratorio di progettazione.

LA: All’interno di questo ecosistema, emerge la questione del rapporto tra competenze concrete, come il disegno, la costruzione e le competenze strutturali, e disposizioni più ampie quali la curiosità, il giudizio etico e l’empatia collaborativa nell’affrontare i problemi dell’architettura. Qual è il loro equilibrio ideale nella formazione? NM: Preferisco non separare questi due ambiti. Acquisendo competenze, si acquisiscono simultaneamente anche valori e, per sostenerli con autentica integrità, è necessario possedere le competenze che li rendono operativi. Mi interessa in particolare che gli studenti sviluppino l’autorevolezza che l’architetto deve possedere nel processo costruttivo, perché è suo compito tenere insieme la squadra di progetto. Gli esecutori leggono i disegni come se fossero delle radiografie: vedono ciò che sai e ciò che non sai. Un buon disegno costruttivo non solo comunica l’aspetto finale dell’edificio, ma anche il processo di costruzione e i possibili problemi che potrebbero verificarsi durante il montaggio. Se queste questioni sono state affrontate e comprese, chi costruisce si sente in buone mani. Competenze di questo tipo dovrebbero essere insegnate a ogni architetto, eppure sono troppo spesso trascurate.

______________________________________________________________________________________________

Luigiemanuele Amabile – Architect and PhD, research fellow of the project DT2 (UdR Università degli Studi di Napoli “Federico II”).

Niall McLaughlin – founder of Níall McLaughlin Architects and Professor of Architectural Practice at the Bartlett School of Architecture, University College London.