Section

Design Toolkit for

Design Teaching

The Recovery Demand

and the Educational Supply

-

about_en

DT2 – The Recovery Demand and the Educational Supply: A Design Toolkit for Design Teaching is a research project, an exchange platform, and a repository of knowledge on the role of architectural education in a time marked by multiple crises, which specifically focuses on the pedagogical model of the design studio.

Its aim is to understand how to promote among future architects a critical vision of design that overcomes the traditional separation of specialized knowledge in the field to devise integrated and interrelated answers to those crises.

For this reason, it looks at the specific place where architectural design is taught as the activity of coordination and control of all the processes, practices, and expertise that guide any spatial transformations – namely the design studio.

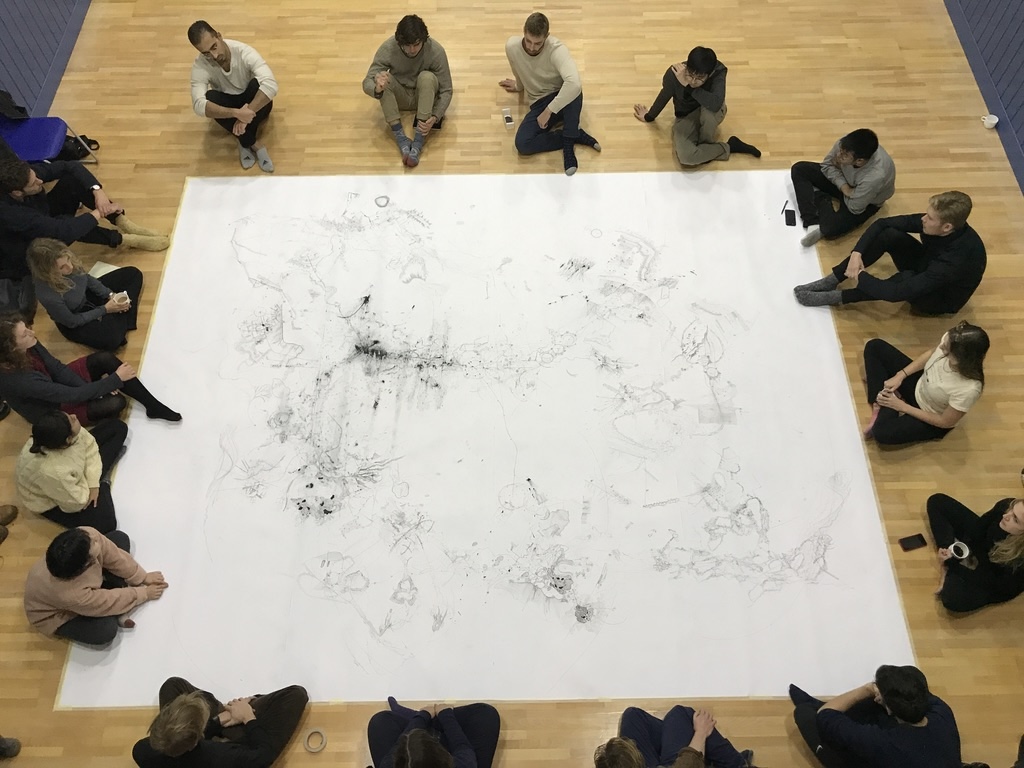

And assuming the integration of all these factors as the true specialistic knowledge of architectural design, it studies all the procedural characteristics that make the studio an immersive training environment based on non-discursive forms of transmission.

DT2 therefore collects a series of outstanding teaching practices and analyzes the aspects that define their methodological infrastructure – like the organization of the class, the calendar, or the coordination with other courses – to provide the basis for their reformulation according to multiple emerging issues.

DT2 – The Recovery Demand and the Educational Supply: A Design Toolkit for Design Teaching è un progetto di ricerca, una piattaforma di scambio e uno spazio informativo sul ruolo della formazione architettonica in un periodo segnato da molteplici crisi, che si concentra sul modello pedagogico del laboratorio di progettazione.

Il suo obiettivo è capire come promuovere tra i futuri architetti una visione critica del progetto che superi la tradizionale separazione delle conoscenze specialistiche nel campo per immaginare risposte integrate a queste situazioni critiche.

Per questo, DT2 guarda al luogo specifico in cui viene insegnata la progettazione architettonica come attività di coordinamento e controllo di tutti i processi, le pratiche e le competenze che guidano ogni trasformazione spaziale – ovvero il laboratorio di progettazione.

E assumendo l’integrazione di tutti questi fattori come il vero sapere specialistico della progettazione architettonica, il progetto studia tutte le caratteristiche procedurali che rendono il laboratorio un ambiente di apprendimento immersivo basato su forme di trasmissione non discorsive.

DT2 raccoglie quindi una serie di pratiche didattiche notevoli e analizza gli aspetti che ne definiscono l’infrastruttura metodologica – come l’organizzazione della classe, il calendario o il coordinamento con altri corsi – per fornire le basi per la loro riformulazione in base a molteplici domande emergenti.

Partners

Politecnico di Milano

Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico IIPeople

Politecnico di Milano

DAStU Dipartimento di Architettura e Studi Urbani

Jacopo Leveratto (PI)

Greta Allegretti

ABC Dipartimento di Architettura, Ingegneria delle costruzioni e Ambiente costruito

Tommaso Brighenti

Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II

DiARC Dipartimento di Architettura

Alberto Calderoni (AI)

Marianna Ascolese

Viviana Saitto

Luigiemanuele AmabileDT2 has been funded by the Italian Ministry of University and Research – MUR under the program PRIN 2022

DT2 has been funded by The European Union – Next Generation EU.

-

I risultati della ricerca

Il progetto della didattica del progetto.

I risultati della ricerca

21.11.2025

Politecnico di Milano

Dipartimento di Architettura e Studi Urbani

Dipartimento di Architettura, Ingegneria delle Costruzioni e Ambiente Costruito

Politecnico di Milano

Edificio 5, Aula Castigliano

Piazza Leonardo da Vinci 26, Milanoore 9:30

A cura di

Tommaso Brighenti

Jacopo LeverattoCon

Marianna Ascolese

Alberto Calderoni

Viviana SaittoOrganizzazione

Greta Allegretti

Luigiemanuele AmabileLuogo

With contributions from: Tommaso Brighenti, Jacopo Leveratto, Alberto Calderoni, Marianna Ascolese, Alberto Calderoni, Viviana Saitto, Greta Allegretti, Luigiemanuele Amabile; Viola Bertini, Edoardo Bruno, Carlo Deregibus, Jacopo Galli, Fabio Guarrera, Andrea Iorio, Francesco Martinazzo, Luca Porqueddu, Andrea Valvason; Luca Monica, Carolina Pacchi, Pierluigi Salvadeo, Maria Cerreta, Domenico Chizzoniti, Gennaro Postiglione; Marco Addona, Francesca Casalino, Giulio Delle Sedie, Luca Esposito, Giorgio Lana, Elena Marchiori, Elisa Mondin, Laura…

-

Summer School L′architettura della didattica

Summer School

L′architettura della didattica

22-26.09.2025

Villa Orlandi, Anacapri

Dal 22 al 26 settembre 2025

Villa Orlandi, Anacapri

Isola di CapriA cura di

Alberto Calderoni

con Marianna Ascolese, Tommaso Brighenti, Jacopo Leveratto, Viviana SaittoOrganizzazione

Greta Allegretti, Luigiemanuele Amabile, Maria Masi, Salvatore Pesarino

“L′architettura della didattica” intende esplorare le prospettive offerte dalla ricerca accademica applicata alla costruzione di metodologie per il laboratorio di progettazione architettonica. Cinque workshop tematici – contesti, modi, tempi, spazi, strumenti – offriranno un′occasione di confronto critico per definire contenuti, modelli e strategie capaci di rispondere a specifiche esigenze formative e a domande emergenti.

La Summer School “L′architettura della didattica” sarà il luogo entro cui si intenderà investigare possibili proposte di progetti pedagogici, nello specifico gruppo scientifico disciplinare della progettazione architettonica, da sostanziarsi a partire dalle attività di ricerca di dottorandi, dottori di ricerca e assegnisti. L′obiettivo della Summer School è sollecitare i partecipanti a sviluppare una proposta individuale di un programma didattico – un brief – attraverso l′esplicitazione di modelli di riferimento, modalità applicative, contesti fisici, tempi e strumenti, propri di un laboratorio di progettazione architettonica.Luogo

Come si struttura un laboratorio di progettazione? Quali sono le sue premesse e le metodologie che sottendono la trasmissione di un sapere architettonico condiviso e condivisibile? Quali i suoi strumenti e in che modo utilizzarli per raggiungere gli esiti previsti?

-

The Intelligence Age

The Intelligence Age

Symposium

10.06.2025

DABC Politecnico di Milano

Politecnico di Milano

Aula 16 B 0.1 – Building 16 B

Via Bonardi, 9, 20133, Milanofrom 9:30 to 18:30

Symposium organized by

Elena Manferdini, Tommaso Brighenti, Elvio Manganaro

With contributions from

Alice Barale, Adil Bokhari, Neil Leach, Elena Manferdini,

Areti Markopoulou, Philippe Morel, Ingrid Paoletti,

Pierpaolo Ruttico, Theodore Spyropoulos, Jason Vigneri-BeaneSessions moderated by

Jacopo Leveratto and Elena Manferdini

As artificial intelligence reshapes how architects work, how should architectural education and research adapt? What should a curriculum look like when the profession it prepares students for is being rewritten in real time?

Organized by the Department of Architecture, Building Engineering, and the Built Environment at Politecnico di Milano and supported by DT2 research project, The Intelligence Age is a public symposium dedicated to examining the evolving role of Artificial Intelligence in architectural education and practice. Taking place on June 10th, 2025, the event brings together leading voices from renowned international institutions to foster dialogue, exchange ideas, and question the shifting landscape of design in the age of intelligence.The symposium serves as a platform for meaningful engagement among educators, researchers, and practitioners, offering a day of conversations structured around thematic duets – paired discussions that allow for contrasting and complementary perspectives. This unique format encourages critical reflection and dynamic interaction across institutional and disciplinary boundaries. Participating schools include SCI-Arc, University of Florida, IAAC, AA-DRL, ETH Zurich, PRATT Institute, The Bartlett School of Architecture, Università degli Studi di Milano, and Politecnico di Milano as the host institution. Their collective involvement highlights the global dimension of this discourse and underscores the shared urgency of redefining pedagogy, and practice in light of AI’s increasing influence. By bringing together a diverse and international academic community, The Intelligence Age positions itself as a landmark event for Politecnico di Milano – a leading institution at the forefront of technology, creativity, and architectural education.

Luogo

With contributions from Alice Barale, Adil Bokhari, Neil Leach, Elena Manferdini, Areti Markopoulou, Philippe Morel, Ingrid Paoletti, Pierpaolo Ruttico, Theodore Spyropoulos, Jason Vigneri-Beane

-

Dieter Dietz. Resonance. Protostructures / Protofigures. Dispositions for Emergent Design

Dieter Dietz. Resonance. Protostructures / Protofigures. Dispositions for Emergent Design

Lezione di Dieter Dietz

13.05.2025

DiARC Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II

Dipartimento di Architettura

Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II

Aula Rabitti, V piano, scala E

via Forno Vecchio 36, Napoliore 16:00

Seminario organizzato con il contributo del dottorato di ricerca Habit in Transition del Dipartimento di Architettura dell’Università degli Studi di Napoli “Federico II”

Saluti

Massimo Perriccioli

Coordinatore Dottorato Habit

Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II

Introduzione

Alberto Calderoni

AI PRIN 2022 DT2

Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II

Lezione di Dieter Dietz

Associate Professor

Director of ALICE Laboratory

École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne

Discussants

Luigiemanuele Amabile

Marianna Ascolese

Gianluigi Freda

Viviana Saitto

Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico IILuogo

Saluti di Massimo Perriccioli. Introduzione di Alberto Calderoni. Lezione di Dieter Dietz. Discussants: Luigiemanuele Amabile, Marianna Ascolese, Gianluigi Freda, Viviana Saitto.

-

Design Teaching for Design Making

Carlana Mezzalira Pentimalli. Quello che stiamo imparando

Lezione di Michel Carlana (IUAV)

Preferisco l’atto del conoscere alla conoscenza

Lezione di Enrico Molteni (Università di Genova)

28.04.2025

DiARC Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II

Dipartimento di Architettura

Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II

Aula LT-S1.1

Palazzo Latilla

via Tarsia 31, Napoliore 14:30

Ciclo di seminari a cura di

Luigiemanuele Amabile e Alberto Calderoni

Con gli interventi di

Marella Santangelo, Alberto Calderoni, Luigiemanuele Amabile,

Marianna Ascolese e Viviana SaittoPresentando modalità didattiche e infrastrutture metodologiche che sostanziano la pratica del progettare, il ciclo di seminari intende investigare, attraverso l’analisi delle esperienze di insegnamento, ricerca e professione condotte da alcuni architetti e docenti italiani ed europei, un campo di azione in cui l’insegnamento del progetto di architettura possa configurarsi come uno strumento necessario non soltanto per riconoscere le domande emergenti, complesse e in perenne evoluzione, ma anche per fornire risposte.

Luogo

Con gli interventi di Marella Santangelo, Alberto Calderoni, Luigiemanuele Amabile, Marianna Ascolese e Viviana Saitto

-

Traces: Reading Landscape and Space

Traces: Reading Landscape and Space

Lezione di Uta Graff (TU Munich)

15.04.2025

DiARC Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II

Dipartimento di Architettura

Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II

Aula Rabitti, V piano

via Fornovecchio 36, Napoliore 14:30

Ciclo di seminari a cura di

Luigiemanuele Amabile e Alberto Calderoni

Con gli interventi di

Marella Santangelo, Massimo Perriccioli, Alberto Calderoni,

Luigiemanuele Amabile, Marianna Ascolese e Viviana SaittoPresentando modalità didattiche e infrastrutture metodologiche che sostanziano la pratica del progettare, il ciclo di seminari intende investigare, attraverso l’analisi delle esperienze di insegnamento, ricerca e professione condotte da alcuni architetti e docenti europei, un campo di azione in cui l’insegnamento del progetto di architettura possa configurarsi come uno strumento necessario non soltanto per riconoscere le domande emergenti, complesse e in perenne evoluzione, ma anche per fornire risposte.

Seminario organizzato con il contributo del dottorato di ricerca Habit in Transition del Dipartimento di Architettura dell’Università degli Studi di Napoli “Federico II”Luogo

Con gli interventi di Marella Santangelo, Massimo Perriccioli, Alberto Calderoni, Luigiemanuele Amabile, Marianna Ascolese e Viviana Saitto.

-

Il progetto della didattica del progetto

Il progetto della didattica del progetto.

Domande per tempi critici

11.11.2024

Politecnico di Milano

Dipartimento di Architettura e Studi Urbani

Dipartimento di Architettura, Ingegneria delle Costruzioni e Ambiente Costruito

Politecnico di Milano

Edificio 5, Aula Castigliano

Piazza Leonardo da Vinci 26, Milanoore 10:00

A cura di

Jacopo Leveratto

Tommaso BrighentiOrganizzazione

Greta Allegretti

Francesco Martinazzo

Andrea ValvasonLuogo

Il progetto della didattica del progetto.Domande per tempi critici11.11.2024 Politecnico di Milano Dipartimento di Architettura e Studi UrbaniDipartimento di Architettura, Ingegneria delle Costruzioni e Ambiente CostruitoPolitecnico di MilanoEdificio 5, Aula CastiglianoPiazza Leonardo da Vinci 26, Milano ore 10:00 A cura di Jacopo LeverattoTommaso Brighenti Organizzazione Greta AllegrettiFrancesco MartinazzoAndrea Valvason ↓ Program.pdf

-

Le diverse forme

Le diverse forme del laboratorio di progettazione.

Offerta formativa e modelli alternativi

26.06.2024

Politecnico di Milano

Dipartimento

di Architettura e Studi Urbani

Politecnico di Milano

Edificio 29 “Carta”, Sala Consiglio, I piano

Piazza Leonardo da Vinci 26, Milanoore 15:00

A cura di

Jacopo Leveratto

Tommaso BrighentiOrganizzazione

Greta Allegretti

Francesco Martinazzo

Andrea ValvasonCon gli interventi di Jacopo Leveratto, Tommaso Brighenti, Greta Allegretti, Francesco Martinazzo e Andrea Valvason e una tavola rotonda con Michela Bassanelli, Francesca Belloni, Giulia Cazzaniga, Federico Di Cosmo, Elvio Manganaro, Giulia Setti, Claudia Tinazzi e Valerio Tolve.

Luogo

Con gli interventi di Jacopo Leveratto, Tommaso Brighenti, Greta Allegretti, Francesco Martinazzo e Andrea Valvason e una tavola rotonda con Michela Bassanelli, Francesca Belloni, Giulia Cazzaniga, Federico Di Cosmo, Elvio Manganaro, Giulia Setti, Claudia Tinazzi e Valerio Tolve.

-

Strategie e prospettive

Strategie e prospettive pedagogiche per il progetto di architettura.

Una generazione a confronto

17.05.2024

DiARC Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II

Dipartimento di Architettura

Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II

Aula Rabitti, V piano

via Fornovecchio 36, Napoliore 9:30

A cura di

Marianna Ascolese

Alberto Calderoni

Viviana SaittoOrganizzazione

Luigiemanuele Amabile

Con gli interventi di Marianna Ascolese, Adriana Bernieri, Daniela Buonanno, Alberto Calderoni, Francesca Coppolino, Bruna Di Palma, Orfina Fatigato, Gianluigi Freda, Paola Galante, Viviana Saitto e Giovangiuseppe Vannelli e una tavola rotonda con Roberta Amirante, Nicola Flora, Ferruccio Izzo, Carmine Piscopo, Marella Santangelo, e tutti gli intervenuti.

Luogo

Con gli interventi di Marianna Ascolese, Adriana Bernieri, Daniela Buonanno, Alberto Calderoni, Francesca Coppolino, Bruna Di Palma, Orfina Fatigato, Gianluigi Freda, Paola Galante, Viviana Saitto e Giovangiuseppe Vannelli e una tavola rotonda con Roberta Amirante, Nicola Flora, Ferruccio Izzo, Carmine Piscopo, Marella Santangelo, e tutti gli intervenuti.

-

Kick-off

DT2 Kick-off Meeting

22.02.2024

DiARC Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II

Dipartimento di Architettura

Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II

Aula Rabitti, V piano

via Fornovecchio 26, Napoliore 9:30

A cura di

Alberto Calderoni

Viviana SaittoOrganizzazione

Luigiemanuele Amabile

Marianna AscoleseConferenza di apertura del progetto DT2, per iniziare a discutere di didattica del progetto e del progetto della didattica, a proposito della situazione italiana, della prospettiva europea, di cosa sta cambiando e di cosa deve cambiare. Con gli interventi di Roberta Amirante, Lidia Gasperoni e Ilaria Valente, e una tavola rotonda con Domenico Chizzoniti, Nicola Flora, Angelo Lorenzi, Pierluigi Salvadeo, Marella Santangelo e Federica Visconti.

Luogo

Conferenza di apertura del progetto DT2, per iniziare a discutere di didattica del progetto e del progetto della didattica, a proposito della situazione italiana, della prospettiva europea, di cosa sta cambiando e di cosa deve cambiare.

-

I risultati della ricerca

Il progetto della didattica del progetto.

I risultati della ricerca

21.11.2025

Politecnico di Milano

Dipartimento di Architettura e Studi Urbani

Dipartimento di Architettura, Ingegneria delle Costruzioni e Ambiente Costruito

Politecnico di Milano

Edificio 5, Aula Castigliano

Piazza Leonardo da Vinci 26, Milanoore 9:30

A cura di

Tommaso Brighenti

Jacopo LeverattoCon

Marianna Ascolese

Alberto Calderoni

Viviana SaittoOrganizzazione

Greta Allegretti

Luigiemanuele Amabile -

Summer School L′architettura della didattica

Summer School

L′architettura della didattica

22-26.09.2025

Villa Orlandi, Anacapri

Dal 22 al 26 settembre 2025

Villa Orlandi, Anacapri

Isola di CapriA cura di

Alberto Calderoni

con Marianna Ascolese, Tommaso Brighenti, Jacopo Leveratto, Viviana SaittoOrganizzazione

Greta Allegretti, Luigiemanuele Amabile, Maria Masi, Salvatore Pesarino

“L′architettura della didattica” intende esplorare le prospettive offerte dalla ricerca accademica applicata alla costruzione di metodologie per il laboratorio di progettazione architettonica. Cinque workshop tematici – contesti, modi, tempi, spazi, strumenti – offriranno un′occasione di confronto critico per definire contenuti, modelli e strategie capaci di rispondere a specifiche esigenze formative e a domande emergenti.

La Summer School “L′architettura della didattica” sarà il luogo entro cui si intenderà investigare possibili proposte di progetti pedagogici, nello specifico gruppo scientifico disciplinare della progettazione architettonica, da sostanziarsi a partire dalle attività di ricerca di dottorandi, dottori di ricerca e assegnisti. L′obiettivo della Summer School è sollecitare i partecipanti a sviluppare una proposta individuale di un programma didattico – un brief – attraverso l′esplicitazione di modelli di riferimento, modalità applicative, contesti fisici, tempi e strumenti, propri di un laboratorio di progettazione architettonica. -

The Intelligence Age

The Intelligence Age

Symposium

10.06.2025

DABC Politecnico di Milano

Politecnico di Milano

Aula 16 B 0.1 – Building 16 B

Via Bonardi, 9, 20133, Milanofrom 9:30 to 18:30

Symposium organized by

Elena Manferdini, Tommaso Brighenti, Elvio Manganaro

With contributions from

Alice Barale, Adil Bokhari, Neil Leach, Elena Manferdini,

Areti Markopoulou, Philippe Morel, Ingrid Paoletti,

Pierpaolo Ruttico, Theodore Spyropoulos, Jason Vigneri-BeaneSessions moderated by

Jacopo Leveratto and Elena Manferdini

As artificial intelligence reshapes how architects work, how should architectural education and research adapt? What should a curriculum look like when the profession it prepares students for is being rewritten in real time?

Organized by the Department of Architecture, Building Engineering, and the Built Environment at Politecnico di Milano and supported by DT2 research project, The Intelligence Age is a public symposium dedicated to examining the evolving role of Artificial Intelligence in architectural education and practice. Taking place on June 10th, 2025, the event brings together leading voices from renowned international institutions to foster dialogue, exchange ideas, and question the shifting landscape of design in the age of intelligence.The symposium serves as a platform for meaningful engagement among educators, researchers, and practitioners, offering a day of conversations structured around thematic duets – paired discussions that allow for contrasting and complementary perspectives. This unique format encourages critical reflection and dynamic interaction across institutional and disciplinary boundaries. Participating schools include SCI-Arc, University of Florida, IAAC, AA-DRL, ETH Zurich, PRATT Institute, The Bartlett School of Architecture, Università degli Studi di Milano, and Politecnico di Milano as the host institution. Their collective involvement highlights the global dimension of this discourse and underscores the shared urgency of redefining pedagogy, and practice in light of AI’s increasing influence. By bringing together a diverse and international academic community, The Intelligence Age positions itself as a landmark event for Politecnico di Milano – a leading institution at the forefront of technology, creativity, and architectural education.

-

Dieter Dietz. Resonance. Protostructures / Protofigures. Dispositions for Emergent Design

Dieter Dietz. Resonance. Protostructures / Protofigures. Dispositions for Emergent Design

Lezione di Dieter Dietz

13.05.2025

DiARC Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II

Dipartimento di Architettura

Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II

Aula Rabitti, V piano, scala E

via Forno Vecchio 36, Napoliore 16:00

Seminario organizzato con il contributo del dottorato di ricerca Habit in Transition del Dipartimento di Architettura dell’Università degli Studi di Napoli “Federico II”

Saluti

Massimo Perriccioli

Coordinatore Dottorato Habit

Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II

Introduzione

Alberto Calderoni

AI PRIN 2022 DT2

Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II

Lezione di Dieter Dietz

Associate Professor

Director of ALICE Laboratory

École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne

Discussants

Luigiemanuele Amabile

Marianna Ascolese

Gianluigi Freda

Viviana Saitto

Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II -

Design Teaching for Design Making

Carlana Mezzalira Pentimalli. Quello che stiamo imparando

Lezione di Michel Carlana (IUAV)

Preferisco l’atto del conoscere alla conoscenza

Lezione di Enrico Molteni (Università di Genova)

28.04.2025

DiARC Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II

Dipartimento di Architettura

Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II

Aula LT-S1.1

Palazzo Latilla

via Tarsia 31, Napoliore 14:30

Ciclo di seminari a cura di

Luigiemanuele Amabile e Alberto Calderoni

Con gli interventi di

Marella Santangelo, Alberto Calderoni, Luigiemanuele Amabile,

Marianna Ascolese e Viviana SaittoPresentando modalità didattiche e infrastrutture metodologiche che sostanziano la pratica del progettare, il ciclo di seminari intende investigare, attraverso l’analisi delle esperienze di insegnamento, ricerca e professione condotte da alcuni architetti e docenti italiani ed europei, un campo di azione in cui l’insegnamento del progetto di architettura possa configurarsi come uno strumento necessario non soltanto per riconoscere le domande emergenti, complesse e in perenne evoluzione, ma anche per fornire risposte.

-

Traces: Reading Landscape and Space

Traces: Reading Landscape and Space

Lezione di Uta Graff (TU Munich)

15.04.2025

DiARC Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II

Dipartimento di Architettura

Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II

Aula Rabitti, V piano

via Fornovecchio 36, Napoliore 14:30

Ciclo di seminari a cura di

Luigiemanuele Amabile e Alberto Calderoni

Con gli interventi di

Marella Santangelo, Massimo Perriccioli, Alberto Calderoni,

Luigiemanuele Amabile, Marianna Ascolese e Viviana SaittoPresentando modalità didattiche e infrastrutture metodologiche che sostanziano la pratica del progettare, il ciclo di seminari intende investigare, attraverso l’analisi delle esperienze di insegnamento, ricerca e professione condotte da alcuni architetti e docenti europei, un campo di azione in cui l’insegnamento del progetto di architettura possa configurarsi come uno strumento necessario non soltanto per riconoscere le domande emergenti, complesse e in perenne evoluzione, ma anche per fornire risposte.

Seminario organizzato con il contributo del dottorato di ricerca Habit in Transition del Dipartimento di Architettura dell’Università degli Studi di Napoli “Federico II” -

Il progetto della didattica del progetto

Il progetto della didattica del progetto.

Domande per tempi critici

11.11.2024

Politecnico di Milano

Dipartimento di Architettura e Studi Urbani

Dipartimento di Architettura, Ingegneria delle Costruzioni e Ambiente Costruito

Politecnico di Milano

Edificio 5, Aula Castigliano

Piazza Leonardo da Vinci 26, Milanoore 10:00

A cura di

Jacopo Leveratto

Tommaso BrighentiOrganizzazione

Greta Allegretti

Francesco Martinazzo

Andrea Valvason -

Le diverse forme

Le diverse forme del laboratorio di progettazione.

Offerta formativa e modelli alternativi

26.06.2024

Politecnico di Milano

Dipartimento

di Architettura e Studi Urbani

Politecnico di Milano

Edificio 29 “Carta”, Sala Consiglio, I piano

Piazza Leonardo da Vinci 26, Milanoore 15:00

A cura di

Jacopo Leveratto

Tommaso BrighentiOrganizzazione

Greta Allegretti

Francesco Martinazzo

Andrea ValvasonCon gli interventi di Jacopo Leveratto, Tommaso Brighenti, Greta Allegretti, Francesco Martinazzo e Andrea Valvason e una tavola rotonda con Michela Bassanelli, Francesca Belloni, Giulia Cazzaniga, Federico Di Cosmo, Elvio Manganaro, Giulia Setti, Claudia Tinazzi e Valerio Tolve.

-

Strategie e prospettive

Strategie e prospettive pedagogiche per il progetto di architettura.

Una generazione a confronto

17.05.2024

DiARC Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II

Dipartimento di Architettura

Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II

Aula Rabitti, V piano

via Fornovecchio 36, Napoliore 9:30

A cura di

Marianna Ascolese

Alberto Calderoni

Viviana SaittoOrganizzazione

Luigiemanuele Amabile

Con gli interventi di Marianna Ascolese, Adriana Bernieri, Daniela Buonanno, Alberto Calderoni, Francesca Coppolino, Bruna Di Palma, Orfina Fatigato, Gianluigi Freda, Paola Galante, Viviana Saitto e Giovangiuseppe Vannelli e una tavola rotonda con Roberta Amirante, Nicola Flora, Ferruccio Izzo, Carmine Piscopo, Marella Santangelo, e tutti gli intervenuti.

-

Kick-off

DT2 Kick-off Meeting

22.02.2024

DiARC Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II

Dipartimento di Architettura

Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II

Aula Rabitti, V piano

via Fornovecchio 26, Napoliore 9:30

A cura di

Alberto Calderoni

Viviana SaittoOrganizzazione

Luigiemanuele Amabile

Marianna AscoleseConferenza di apertura del progetto DT2, per iniziare a discutere di didattica del progetto e del progetto della didattica, a proposito della situazione italiana, della prospettiva europea, di cosa sta cambiando e di cosa deve cambiare. Con gli interventi di Roberta Amirante, Lidia Gasperoni e Ilaria Valente, e una tavola rotonda con Domenico Chizzoniti, Nicola Flora, Angelo Lorenzi, Pierluigi Salvadeo, Marella Santangelo e Federica Visconti.

-

Atlas

Approaches

-

Learning by teaching

Some words, much more than others, allow us to structure reflections that often run the risk of being taken for granted because they are commonly used or belong to everyday life. Learning and teaching seem, nowadays, to be terms that have lost their meaning; contrary to this trend, however, they preserve the core of the…

-

The architecture of learning

Two different movements are linked to the concepts of teaching and learning. Often used as synonyms, their etymology tells of two distinct predispositions. In the first case, the action focuses on the person who teaches, instructs, shows and trains (gr. DIDAKTIKÓS instructive, from DIDAKTIKÓS which can be taught, Didaxis lesson, and derives from the same…

-

Reconsidering hierarchies and happiness in the project

EB: Jason Hilgefort, founder of L+CC (Land+Civilisation Compositions), since we met at the Shenzhen Biennale in 2019, we have often discussed the value of projects, both in professional practice and in university classrooms, as something that should be broader than architecture itself. In your case, these ideas have also led you to develop local activism…

-

Layering Contexts

Luigiemanuele Amabile in conversation with Maria Conen. Knowing a place, before delving into the complex process of designing architecture, represents one of the first fundamental acts that architects should indulge in. For Maria Conen, observation is a layered practice in which the existing conditions of a place are approached with equal attention, allowing different realities…

-

Teaching from within: architecture as process and practice

Luigiemanuele Amabile in conversation with Thomas Padmanabhan. In a context of multiple crises like the one we are experiencing, architecture has little room to shape public discourse. The contemporary design process – so complex and shaped by countless variables – makes the coexistence of teaching and professional practice one of the few viable ways to explore alternatives…

-

Architecture as social-material practice

Luigiemanuele Amabile in conversation with Niall McLaughlin. What distance, or what proximity, exists between the tangible conditions that architecture must address and the possibilities for speculation within a design studio? This question forms the basis of the interview with Níall McLaughlin, which explores the ways in which a project emerges at the intersection of materials,…

-

Architecture within uncertainty

Luigiemanuele Amabile in conversation with Christoph Grafe. As a historian and theorist of architecture, Christoph Grafe reflects on the design studio as a pedagogical framework in which reuse and adaptation are considered from cultural, aesthetic and technical perspectives. He emphasises the importance of balancing student freedom with a clear, adaptable structure, and highlights the role…

-

Questioning typologies, or the hybrid future of architectural design

Luigiemanuele Amabile in conversation with Andreas Lechner. Moving between theory, practice and pedagogy, Andreas Lechner describes the design studio as a place where architecture engages with reality while retaining its poetic and critical agency. The project is at the heart of this approach, serving as a medium through which ecological urgency, social engagement and everyday…

-

We don’t have all the answers – we explore together

Luigiemanuele Amabile in conversation with Marius Grootveld. Marius Grootveld conceives of the design studio as a collective and cumulative process, in which students develop autonomy within a shared lineage of ideas, rather than through isolated positions. At RWTH Aachen University, each studio builds on the outcomes of previous ones. This allows individual trajectories to emerge…

-

Teaching repetition

Valentina Noce in conversation with Andreas Lechner. VN: The first thing I wanted to talk to you about is my struggle when teaching between two kinds of approaches. The first one is almost like a psychological, psychotherapy approach to students – where you act as a kind of disturbing observer. You let the students do what…

-

Teaching architecture in a fragmented world

Luigiemanuele Amabile in conversation con Wolfgang Brune. Shaped by an awareness of the fragmented nature of the contemporary world, Wolfgang Brune’s approach to teaching places architectural education between urgency and continuity. Environmental responsibility, resource awareness and social issues are acknowledged as inevitable, yet they are approached through a return to a fundamental aspiration: designing buildings…

-

The pedagogy of the complete gesture

The philosophy of the gesture originates within American pragmatism, whose essential characteristic is that it is an anti-dichotomous philosophy, standing against the distinctions between description/norm, body/spirit, mind/brain, theory/practice, and so on – distinctions rooted in Cartesian and Kantian culture. Of course, we are talking about a certain interpretation of Descartes and a certain interpretation of…

-

The design studio as a research program

“Sense of possibility”: without that, the pedagogy of design studios would make no sense, precisely. With the 1993 reform, courses in architectural composition and design began to be called studios because it was recognized that architectural design is learned by doing; but perhaps it was not stated just as clearly that in design studios, doing…

-

Experimental pedagogy and design studio

Rethinking pedagogy at an experimental level means renegotiating a field of themes and practices in order to train architects capable of confronting the challenges of the contemporary world and projecting them into the future. This entails reestablishing a creative balance between the construction sector and architecture as one of the principal inventive practices contributing to…

Schools

-

Rethinking the knowledge of form

Luigiemanuele Amabile in conversation con Nana Biamah Ofosu. Architecture, in Nana Biamah-Ofosu’s account, can no longer be understood through form alone. Drawing on her teaching between Kingston University London and the Architectural Association, she reframes architectural knowledge as a field shaped by identity, history, and lived experience, asking insistently who architecture represents and who it…

-

Boîtes-en-valises. Discontinuous genealogies for Venice, Berlin, New York

Signs of presage Presage is neither a definitive announcement nor a vision shaped by mystical or teleological determinism. A sign that alludes to something not yet revealed, praesagium indicates the possibility of reading in observable facts – which are remnants, interruptions, silences and failures – clues to futures that are potentially already inscribed in the…

-

Transmitting and innovating: the teaching tradition in Venice

The word tradition derives from the Latin tradere, meaning “to hand down” or “to transmit”. Tradition is therefore a word inherent to the role of “educators”, understood in its broadest sense, especially in the teaching of architectural design. Tradition in design is the transmission of knowledge that must take place in the design workshops of…

-

Rigor and synthesis

Luigiemanuele Amabile in conversation with Nuno Valentim Lopes. The interview with Nuno Valentim Lopes outlines a pedagogical position grounded in rigour, continuity, and synthesis, framing the FAUP in Porto as a school where architectural education is built around collective work and a strong foundational formation. The design studio emerges as a shared framework integrating design,…

-

The studio environment

In American schools, particularly those we might define as elite, there has always been – or there was for a long time – a strong emphasis on experimentation, meaning an attempt to push boundaries in order to explore ways and approaches to thinking about architecture that presumably are not immediately applicable in the professional field…

-

Notes for a systematics of the educational project

I have always been deeply interested in discussing pedagogy; I believe it’s crucial to reflect on this topic. Not only from a theoretical standpoint but especially starting from how I personally have addressed practical problems that have arisen in this field across the various universities where I have taught and in relation to the role…

-

The Italian difference in architectural education

Teaching experience in other faculties, in other places, in other countries has indeed been essential for me to understand whether and what the differences are compared to our system. But before addressing this issue, I want to touch on a specifically Italian matter that worries me greatly and concerns the present; a negative difference compared…

Programs

-

Introduction to the project: the IncipitLab experience

The need to establish IncipitLab – coordination of the first-year Architectural Design Laboratories of the three-year, master’s and single-cycle master’s degree courses in Architecture, and three-year and/or master’s degree courses in Construction Engineering-Architecture – stems from a series of teaching experiences gained in this specific academic year, which it was appropriate to reflect on. This…

-

Andante veloce. Regarding two variations in intensity

For better or worse, in the field of architectural education, there is no parameter by which to measure the greater distance between training and profession than that which concerns project timescales. For better, because it must always be remembered that the educational objectives of an architecture degree do not coincide, nor should they coincide, with…

-

Crush-up: collaborations for architectural futures

Luigiemanuele Amabile in conversation with Ignacio Borrego At the Technical University of Berlin, teaching within CoLab conceives of the design studio as an open field of enquiry, rather than a predefined trajectory. Architectural education is framed as an exposure to a variety of questions, methods and tools, enabling students to find their own way through…

-

Designing transitions: transdisciplinary urban and territorial pedagogies

Konstantinos Venis in conversation with Nancy Couling and Tommaso Pietropolli. KV: The selection criteria were the characteristics and curriculum of your programme. It is a transdisciplinary joint programme focusing on design as a tool of synthesis in a transdisciplinary environment, integrating urban studies, postcolonial thought, the Anthropocene, and interdisciplinary approaches in site-specific work across urban…

-

Building narratives for communities

The world of architectural education is becoming more complex with each passing year. At the turn of the millennium, design culture found itself having to face challenges that once seemed far from the world of “bella forma”, of an architecture that, at least in Europe, until not long ago spoke of the autonomy of the…

-

The capacity for (general) vision as a necessary specialism

I will begin with a statement that I know today risks being seen as outdated: the design studio is and must continue to be the “backbone” of architectural studies. […] Not even the recent reform of the degree classes introduced by Ministerial Decrees no. 1648 and no. 1649, respectively for bachelor’s and master’s degrees, in…

-

Coherence and the role of the design studio

Recent history has shown that, in the specific case of the most genuinely original educational experiences in the field of architecture, what defines the character, motivation, specificity, and all the peculiar features of experimental teaching are identified simply with a school, not with a department, and even less with a degree program. On the other…

-

Architecture in a small school

A contribution that seems interesting to me, regarding the experimentation that can be carried out within Design Studios, is the one we have been developing for several years now in the Master’s Degree course active at the Mantua Territorial Campus. […] The course was conceived around a prevailing theme concerning the relationship between architectural design…

-

Shifting identities

I believe that, in order to try to define the role of the design studio in a school of architecture, it is first necessary to ask what the meaning of design is in relation to the current conditions of urban space, and more generally, of inhabited space. These are ever-changing conditions that are shaped by…

-

The project for a new degree program

For the new Master’s degree program in Architecture for Communities, Territories and the Environment at DIARC, we chose to begin by outlining the fields and contexts in which an architect can operate today, beyond traditional areas of action, focusing carefully on the present, on the ongoing social and cultural changes, on humanity and the environment;…

Courses

-

For vertical coordination: Laboratorio34

Laboratorio34 is an educational experiment, conceived and coordinated by Andrea Sciascia, which saw, for the academic years 2022-23 and 2023-24, coordination between the third and fourth year Architectural and Urban Design laboratories (Laboratorio34). This experiment, which aims to bring together a large number of students and teachers around the same theme and project area, draws…

-

Experimental forms of intensive teaching delivery: the WeDARCH Laboratory

Andrea Sciascia, Antonino Margagliotta, Fabio Guarrera, Giuseppe Di Benedetto, Giuseppe Marsala, Luciana Macaluso, Manfredi Leone, Paolo De Marco, Santo GiuntaThe WeDarch Laboratory is an experimental intensive teaching programme designed as an alternative to the traditional Architectural and Urban Design Laboratory model established by the Ministerial Decree of 24 February 1993. The University City of Palermo was chosen as the location for the experiment, a large area crossed by a dense vegetation system, which extends…

-

Rewriting a pre-existing text by composing syntax

The theme of the single-family home has always been a particular area of design experimentation, allowing architects to explore new expressive and linguistic horizons in architecture. It is a field of research that is somewhat isolated, probably because it requires reflection on the place where human thoughts, memories and dreams interact, but at the same…

-

Invention exercises. The project of a house for oneself

Choosing to dedicate the first-year workshops to the theme of house design means immediately placing a fundamental question for the discipline of architecture at the centre of the students’ reflection: the question of the meaning of living. “What does it mean to live?” is an unavoidable and inexhaustible question, for which there is no definitive…

-

Living in the landscape, inhabited by the landscape

The architecture of the house is, in general terms, the theme around which the teaching activities of Architectural Design Laboratory I are structured. This course is conceived as an integrated course that sees the interaction of the disciplines of Architectural Composition with those of Architectural History and Construction Technology. Reflection on that architectural organism that…

-

ἐνιαυτόσ or the long time required to train an architect

“The essence of the architectural problem today is not the search for impossible connections with the past, but the full exploitation, with a free spirit, of the construction possibilities that technical progress has given us. Above all, it is necessary to give soul and aesthetic expressiveness to new building techniques, fully developing their unlimited richness.…

-

Andante veloce. Regarding two variations in intensity

For better or worse, in the field of architectural education, there is no parameter by which to measure the greater distance between training and profession than that which concerns project timescales. For better, because it must always be remembered that the educational objectives of an architecture degree do not coincide, nor should they coincide, with…

-

Exceptions. The case of Thematic Laboratories

The thematic laboratory, in its current form, evolved from a project within the Master’s Degree programme in Architecture Built Environment Interiors (ACI) and its English-language counterpart Architecture Built Environment Interiors (BEI) at the School of Architecture, Urban Planning and Construction Engineering at the Politecnico di Milano. The course, which began in the 2017-2018 academic year,…

-

Three studios 2. Teaching design research

When understood as a research operation, the teaching of the project allows us to advance some reflections on the construction of an idea of space, reflecting on what John Hejduk explained during the exhibition and in the catalogue Education of an Architect: a point of view, regarding the exercise of the Cube Problem: “the student…

-

Designing the teaching of the project

“Designing project teaching” refers to the attempt to equate architectural project teaching strategies with a project itself, which aims to construct a workshop “space” based on a series of assumptions and supporting an idea to be developed at different times and through specific tools. To explore these aspects in greater depth, reference is made below…

-

Living in the laboratory

«Education today is a great obsession. It is also a great necessity». It is not difficult to apply these words, which sparked debate in the 1960s and 1970s on the American educational process, when the right to education and the need to discuss teaching as a matter of social integration were urgent and deeply political…

-

Utilitas, firmitas and venustas

Alberto Bologna in conversation with Andrea Valeriani AV: The first-year workshop is probably the most complex of all those that a teacher has to deal with during the course of study because it has the dual task of teaching students both a design method and the ability to represent and communicate it. How is your Workshop…

-

The first apprenticeship. Between doing and watching others do

The Design Laboratory I welcomes a class of about 80 students enrolled in the first year of the three-year degree course in Architectural Sciences. The course is structured in two semesters with compulsory attendance, the first taught by Vincenzo Moschetti and the second by Fabio Balducci who, with the support of a group of tutors,…

-

The conditions for a “cours préparatoire”

Times and numbers My first reaction concerns the number of students mentioned in the course description. Such a large number makes it difficult to assess the students’ progress – something I consider fundamental – or to carry out a fair evaluation or comparative analysis of the results. At the Politecnico di Milano, we have a…

-

Preparatory work and architectural design

The development of a first-year architectural design workshop programme is in itself a fundamental undertaking. Not only because it represents the student’s first “encounter” with the design experience, but also because, as the term “workshop” suggests, it requires the transmission of knowledge that is not linear in nature. Rather, it is made up of trials,…

-

Material Typologies

Luigiemanuele Amabile in conversation with Tina Gregoric. What does it mean to place material conditions at the origin of architectural education? In this interview, Tina Gregoric presents the design studio as a framework that resists standardisation and must be recalibrated each time in relation to the site, the topic and the scale. Within the condensed…

-

Form is not enough

Luigiemanuele Amabile in conversation with Bernadette Krejs. The architectural design studio is at a critical juncture. As the field of architecture confronts its role in ecological collapse and social inequity, traditional pedagogical approaches centred on form and individual authorship are increasingly being seen as insufficient. Bernadette Krejs of the Institute of Housing and Design at…

-

Precision and experimentation in the design studio

Luigiemanuele Amabile in conversation with Mikael Bergquist Mikael Bergquist envisages the design studio as a shared environment in which architectural knowledge is developed through small groups, pair work and the consistent use of a designated space. At KTH in Stockholm, social issues, materials, technology, sustainability, and working with existing structures are considered alongside the discipline’s…

-

Teaching, conflicts, ecology

Maria Masi in conversation with Miguel Mesa del Castillo Clavel. MM: Your work moves between architectural design, academic research, and intensive teaching activity, and is marked by a consistent interest in the relationship between space, ecologies, and society. How do these experiences influence the structure of your courses, and what relationships do they weave between…

-

The studio in numbers

The role of the design studio within architecture schools is characterized by a dual identity. On one hand, it is a foundational and strongly constitutive element of the educational offering for students, who find in the laboratory the opportunity to engage and challenge themselves with the discipline of design. The design laboratory, in fact, defines…

-

-

Rethinking the knowledge of form

Luigiemanuele Amabile in conversation con Nana Biamah Ofosu.

Architecture, in Nana Biamah-Ofosu’s account, can no longer be understood through form alone. Drawing on her teaching between Kingston University London and the Architectural Association, she reframes architectural knowledge as a field shaped by identity, history, and lived experience, asking insistently who architecture represents and who it is for. Formal and aesthetic languages are interrogated through questions of migration, race, ecology, and material politics, revealing how European cities and their images are deeply entangled with colonial histories and systems of extraction.Rather than reducing architecture to building production, Biamah-Ofosu expands it to include writing, speaking, narration, and critical reflection, arguing that knowledge in architecture must also account for what should not be built. Education, in this sense, becomes a slow and collective process, grounded in dialogue, interdisciplinarity, and generalist formation. Against optimisation and narrow specialisation, she defends time, shared foundations, and curiosity as essential conditions for an architectural practice capable of engaging the complexities of the twenty-second century.

LA: Do you think architecture can still be considered a discipline in which the knowledge of form – its formal and aesthetic aspects, and the representational power of buildings – is the most relevant thing to study? Or should we be focusing elsewhere?

NBO: Starting with your context – the Italian setting and its broader European outlook – that’s interesting to me, especially in terms of questioning: who is European today? Who is here? Why are they here? What does architecture mean to them? What kinds of conceptualizations of architecture and the built environment do they bring?

Personally, I consider myself British, but I’m also Ghanaian – I have African heritage. For me, European identity is complex. So the question of the knowledge of form and the spatial planning of cities should also be critiqued from the perspective of: who is the city for? In London, for instance, the population is far more diverse today than it was 50 years ago, during post-war reconstruction when the city may have been imagined for a particular kind of citizen. According to statistics from around 2020 or 2021, London had more people who were non-white or not born in the UK than white British citizens. That fact alone raises essential questions about urbanism and architectural language.

So, to me, any critique of the knowledge of form should begin by asking: who is this architecture representing? Who is it for? I understand architecture broadly – not just as building-making. In my practice, we design, write, speak about buildings. That breadth of engagement is a compelling way to consider the knowledge of form. Architecture’s form is not just what is built – it includes narratives, histories, and lived experiences. We need to connect these stories to the built environment. If we rely only on formal frameworks, we risk excluding the “why”. We create a practice focused solely on visual or image-driven outcomes, which I believe is increasingly irrelevant.

Especially when we consider identity politics, material resources, the future of our planet – the very foundations of architectural language need to be rethought. For example, the pristine language of concrete is no longer adequate when we are grappling with environmental constraints. We are at odds: the materials we idealize don’t align with the values we now claim to hold. And then there’s the question of migration, of making a home elsewhere. That affects our understanding of form. Historically in Europe, we have privileged a dominant architectural language. But we need to open ourselves to many languages – plural and diverse. We must understand that Western traditions are only one part of a much larger story. Even in European cities like London, the image of the city is indebted to histories of extraction and colonization. Post-war housing was only possible because Britain sourced labour and materials from its colonies. If we understood this better, we might read the built environment quite differently.

The knowledge of form should include these other stories. It shouldn’t be framed purely through a Western lens. And beyond form, we must rethink what we consider “knowledge” in architecture. Is knowledge only useful if it builds something? Especially in Europe, we should perhaps be building less. That may not apply everywhere, of course, but here, yes. We need to connect architecture to identity, material politics, democratic structures. Why aren’t architects more involved in public health, or city governance, or how funds are allocated? We should use our skills more broadly. Why not ecology, infrastructure, systems thinking? The discipline needs to expand beyond designing single buildings.

If we go in that direction, we must also rethink architectural education. We need to engage with other disciplines. That’s where real enrichment lies. And that brings me to a fundamental question: who is the architect of the 22nd century? What do they look like, what do they do, and how do they practice? I think they’ll be very different from their 20th- or even 21st-century counterparts.LA: Earlier, you mentioned European heritage, and how it relates to your own background and teaching context. I’d like to ask: is there anything from the 20th-century architectural schools of thought that you believe remains relevant? Are there models or values that continue to inform your way of teaching today, especially given your experience at both Kingston and the AA?

NBO: Yes. So I studied at Kingston for both my undergraduate and postgraduate degrees – a very solid architectural education. But at the time, questions about identity, race, and how your background affects your understanding of space and architecture weren’t addressed. The education was delivered through a very Western lens, reflecting traditions tied to the European city, the architectural room, the notion of urbanity. Architecture was seen as something purely formal. The architect was the master – almost a god-like figure. But as I matured, especially by connecting more deeply with my cultural heritage, I began to question that. Many cultures understand making and living as deeply intertwined, and that, to me, has greater value.

Lesley Lokko writes in African Space Magicians about how many African languages don’t even have a word for “architect”. They may have words for building, or for a maker, but not “architect”. And the Western profession of architecture is relatively young – only a few hundred years old. After I graduated, I began to realize how much had been left out of my education – particularly in terms of how architecture relates to power, history, and economics. The built environment is not just the product of good design. It’s shaped by political and financial forces. And we should talk more honestly about that. Architecture is not apolitical, and it’s not benign.

As for influences, I started teaching immediately after I graduated. I taught at Kingston for four years and then joined the AA. That was a turning point. The AA felt like a different world – more critical, more open to other ways of thinking. I had been trained in a specific school of thought, and I realized I had never truly had my principles challenged by others. Taking the position at the AA allowed me to do that. I have come to value the unit system in design teaching, which both Kingston and the AA use. I was educated in it, and I still teach within it. I know there’s been criticism in recent years, but I think the model itself is strong. The key is that units must not be run by a single figure. Architectural education should not reproduce the master-apprentice dynamic. I believe units should always be co-taught – at least by two people. That creates dialogue, and that’s crucial.

The course at KNUST (Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Ghana) was a four-year degree. For a long time – and I think it may still be true – the first two years were shared by all built environment students: building technologists, architects, urbanists. Only in the third and fourth year did they specialize. I think there’s something valuable in that – in sharing foundational knowledge across disciplines. In a world with polycrises – where problems are not siloed – we can’t rely on closed professions to deliver solutions. We need to learn to speak to each other. What if we shared an educational foundation among planners, architects, building physicists – even public health or ecology specialists? That kind of shared education could build a more productive built environment – and stronger professional collaboration. So yes – I think both the unit system and interdisciplinary foundations are valuable pedagogical models.LA: One of the last things you said was about broadening the base of architectural education while retaining a common ground. There’s been a long debate about the architect as a generalist – someone who knows a bit of everything but doesn’t specialize too deeply. That debate may be over now, given all the new challenges we face, but I wonder – do you think architectural education should still support a generalist approach, rather than pushing students to specialize?

NBO: I think I fall more on the generalist side – especially in the beginning, during the formative years of an architect’s education. So definitely at the bachelor’s level, I believe in a generalist education and in building competency. Those are the two things for me: undergraduate education should be about developing competency – learning the skills of your profession – and approaching it through a generalist lens. Because architecture, in a world that now leans toward specialization and breaks problems into hermetic bubbles, is one of the last spaces where generalism still thrives. And those hermetic bubbles – the gaps between disciplines – are the real danger zones. If you imagine drawing all these disciplinary boxes – the problems often lie in the spaces between them, where no one takes responsibility. We keep further siloing knowledge, and within each silo we break it down even more – so you have people who are highly specialized in one narrow thing. But who helps us talk across the silos? That used to be the architect.

By letting go of that role, I think we have devalued our own skills. As the world moved toward specialization, one of the greatest strengths – and pleasures – of architectural education remained its generalist foundation. It’s still one of the few degrees where you learn a bit of everything. And I don’t think that a bachelor’s in architecture should necessarily produce a person who becomes a building architect in the traditional sense. It’s such a valuable degree precisely because of its pluralistic approach – it teaches you about economics, social issues, culture, politics. It allows you to have real conversations – across fields. I think the generalist has been unfairly demonized – portrayed as someone who knows nothing well. There’s this English phrase – «Jack of all trades, master of none» – but the part that’s often forgotten is: «… but oftentimes better than master of one», That forgotten ending changes everything. And I think it really captures what a good generalist education offers. To me, that’s what architecture provides – or should provide. We have painted the generalist as someone weak, but they are often better positioned than someone who only knows one thing. I also think about Professor Lesley Lokko – a key figure redefining architectural education and the architect’s future role. In her RIBA Gold Medal speech in London, she talked about the idea of the “amateur” – and the root of that word meaning to love. An amateur is someone who practices because they love what they do – not because they seek perfection, but because they want to keep inquiring and growing. That kind of generalist approach values curiosity – and values the amateur. Of course, we need specialisms too. But a world of specialists without common ground is not a good one.LA: I read an interview you gave in 2020 where you described how your students were asked to read and discuss texts – and you said students need time, that they need to slow down. Has anything changed in the last five years? Because it seems architecture, even education, is now heavily focused on optimization, results, schedules. Do you still believe in moving slowly?

NBO: I still think students need time. Everyone needs time, actually. Good things take time. And where better to invest that time than in educating people who will shape our future? I think that interview referred to a second-year student group. That level really needs time: time for conversation, time to take things in, to share, to understand. Time to think out loud, even. And that can’t be done alone. That’s why architecture education suffered so much during the pandemic. Because that kind of time also depends on being in community – in a room together, in dialogue. That conversation isn’t just verbal – it’s also communicated through physical actions, through objects. So it’s about time – and presence. During the pandemic, I felt a real sense of loss for first-year architecture students. I remember my own first year: I came from a fine art background, so I could draw – but I didn’t have the technical skills, the architectural language. It took me a while to figure things out. And I can’t imagine doing that alone, in my bedroom at home, during lockdown. That kind of learning also happens in the studio – by reading, drawing, working together. So now, I’d say: yes, it’s about time, but also about how we spend that time – what we do with it. Are we working cooperatively, in dialogue, or just optimizing? Of course, I do a lot of things remotely – like this interview – and I believe strongly in sharing ideas across borders. That’s essential. But it’s also true that everything I just said about time completely contradicts the neoliberal university model – with its timesheets, timetables, credit conversions. Design studios, for instance, are often given the highest credit load because they are time-intensive. But those numbers – while they might feel important – are also arbitrary. We need to ask: are we really educating, or are we just certifying? There’s a difference between certification and education. The time factor is tricky, and I don’t yet have a clear answer – but it’s something I want to think more about. It opens up other modes of education – ones that aren’t about certification, but about time to think and explore. And for me, thinking is doing – not just cerebral, but also physical, embodied. That’s why I loved teaching in Professor Lesley Lokko’s Biennale College. It offered time to think, to discuss, to explore – but without the pressure of certification. I’m not saying we should eliminate certification. We are a profession, and that matters. But I do think we need to explore more plural forms of education – ones that allow us to create new forms of knowledge, and new forms of form itself.

______________________________________________________________________________________________

Luigiemanuele Amabile – Architect and PhD, research fellow of the project DT2 (UdR Università degli Studi di Napoli “Federico II”).

Nana Biamah Ofosu – Professor at Kingston University London and Architectural Association. -

For vertical coordination: Laboratorio34

Laboratorio34 is an educational experiment, conceived and coordinated by Andrea Sciascia, which saw, for the academic years 2022-23 and 2023-24, coordination between the third and fourth year Architectural and Urban Design laboratories (Laboratorio34). This experiment, which aims to bring together a large number of students and teachers around the same theme and project area, draws on some of the educational characteristics of the Faculty of Architecture in Palermo, based on regulations that preceded the 1993 university reform, which was also based on the desire to bring together students from different years and with different levels of experience.

The cultural focus of the workshop is the theme of ecological transition, now at the centre of debate and policy at international, national and local level. The theme was addressed starting from the recognition of certain unbuilt urban resources, primarily Monte Pellegrino and its Oriental Nature Reserve, and the Parco della Favorita, the ancient Bourbon hunting estate located in the northern part of the city of Palermo. Intended as potential colonising systems, the mountain and the park were interpreted as territorial entities and landscape structures capable of generating new forms of city and urban fabric, in light of the new questions posed by ecological transition: presidia of public space consisting of woods, vegetable gardens and orchards that imply new modifications and interpretations of contemporary city spaces.

The scope of the design experiment was the two areas of the Monte Pellegrino aquifer: the south-east, sandwiched between the mountain and the sea and marked by the large monumental cemetery of Rotoli (for the academic year 2022-23); and the north-western area, where the large green portion of the Parco della Favorita forms an interstice between the mountain and the city of Sacco, the northern residential expansion that marked the construction of the city from the 1970s onwards (for the academic year 2023-24).

The projects identified themes and issues for broader research focusing on the new relationships between nature, architecture and the city, and provided specific responses to the specific needs of each site, while looking to the ecological horizon as a response to a social demand that can no longer be ignored, concerning the changes taking place on the planet.

__________________________________________________________________________________________

Per un coordinamento verticale: il Laboratorio34

Laboratorio34 è una sperimentazione didattica, ideata e coordinata da Andrea Sciascia che ha visto, per gli anni accademici 2022-23 e 2023-24, un coordinamento fra i laboratori di Progettazione Architettonica e Urbana del terzo e del quarto anno (Laboratorio34). Tale sperimentazione – volta a concentrare un elevato numero di studenti e docenti intorno a uno stesso tema e a una stessa area di progetto – recupera alcune peculiarità didattiche della Facoltà di Architettura di Palermo, basate su delle norme ordinamentali che hanno preceduto la riforma universitaria del 1993 che si fondava anche sulla volontà di far lavorare insieme studenti di annualità e con esperienza diversa.

Il laboratorio ha come fulcro culturale la tematica della transizione ecologica, ormai al centro del dibattito e delle politiche in ambito internazionale, nazionale e locale. Il tema è stato affrontato a partire dal riconoscimento di alcune risorse urbane non costruite a partire in primo luogo dal Monte Pellegrino e dalla sua Riserva Naturale Orienta, e dal Parco della Favorita, l’antica tenuta di caccia Borbonica posta nella porzione nord della città di Palermo. Intesi come potenziali sistemi colonizzatori, il monte e il parco sono stati interpretati come entità territoriali e strutture di paesaggio in grado di generare nuove forme di città e di tessuto urbano, alla luce delle nuove domande poste dalla transizione ecologica: presidi di spazio pubblico costituito da boschi, orti e frutteti che implicano nuove modificazioni e interpretazione degli spazi della città contemporanea.

Il campo di applicazione della sperimentazione progettuale sono state le due aree di falda del Monte Pellegrino: quella sud-est, serrata tra il monte e il mare segnata dal grande cimitero monumentale dei Rotoli (per l’anno accademico 2022-23); e quella nord-ovest, in cui l’ampia porzione verde del Parco della Favorita si costituisce come interstizio tra il monte e la città del sacco, l’espansione residenziale nord che ha segnato la costruzione della città a partire dagli anni Settanta del novecento (per l’anno accademico 2023-24).

I progetti hanno individuato temi e questioni di una ricerca più ampia che vede nelle nuove relazioni tra natura, architettura e città il suo centro di riflessione; e hanno dato risposte puntuali alle necessità specifiche di ogni sito, guardando tuttavia all’orizzonte ecologico come risposta ad una domanda sociale non più eludibile che riguarda i cambiamenti in atto nel pianeta.

__________________________________________________________________________________________

Andrea Sciascia – Full Professor in “Composizione architettonica

e urbana”, Dipartimento di Architettura di Palermo (DARCH), Università degli Studi di Palermo.Giuseppe Di Benedetto – Full Professor in “Composizione architettonica

e urbana”, Dipartimento di Architettura di Palermo (DARCH), Università degli Studi di Palermo.Luciana Macaluso – Associated Professor in “Composizione architettonica

e urbana”, Dipartimento di Architettura di Palermo (DARCH), Università degli Studi di Palermo.Giuseppe Marsala – Full Professor in “Composizione architettonica

e urbana”, Dipartimento di Architettura di Palermo (DARCH), Università degli Studi di Palermo.Zeila Tesoriere – Associated Professor in “Composizione architettonica

e urbana”, Dipartimento di Architettura di Palermo (DARCH), Università degli Studi di Palermo. -

Experimental forms of intensive teaching delivery: the WeDARCH Laboratory

Andrea Sciascia, Antonino Margagliotta, Fabio Guarrera, Giuseppe Di Benedetto, Giuseppe Marsala, Luciana Macaluso, Manfredi Leone, Paolo De Marco, Santo GiuntaThe WeDarch Laboratory is an experimental intensive teaching programme designed as an alternative to the traditional Architectural and Urban Design Laboratory model established by the Ministerial Decree of 24 February 1993.

The University City of Palermo was chosen as the location for the experiment, a large area crossed by a dense vegetation system, which extends from the outer suburbs to the edge of the historic centre and is surrounded by heavily urbanised neighbourhoods. A fenced-in enclave, it appears as an “island” with few connections to the surrounding city. The origin of this condition is due to the adherence to the model of campuses as closed and self-sufficient systems; to its location in an area originally outside the city, now reached by late 20th-century urbanisation; and to an underestimation of the role of infrastructure in the life of these settlement systems, which has characterised Palermo’s urban policy choices over the last fifty years.

Among the objectives underlying the WeDARCH Laboratory’s design activities were the study of two general aspects: one of an urban nature and the connections between the campus and the city; the other linked to the internal functioning of the citadel, its open and community spaces, its internal mobility and the possibility of introducing new functions for both teaching and the social life of the community.

The projects therefore expressed the intention to increase the degree of porosity of the university city by working on a complex system of cross-cutting relationships. The aim was to define its boundaries, where the campus interfaces with the surrounding residential neighbourhoods and the western walls of the historic city; to enhance the role of the continuous vegetation system of Parco Cassarà-Fossa della Garofala-Giardino d’Orleans; to strengthen distant relationships with the nearby Civico and Policlinico hospitals, as well as with the Oreto valley.

The reduction of vehicular traffic and artificial surfaces, the implementation of vegetation and the design of gardens, and the introduction of services in addition to those related to education, found their focus in the design of open-air classrooms, which allowed for the development of outdoor teaching and the public and collective use of open spaces for cultural and leisure activities. Finally, the aim of involving students in the design of the spaces and places they inhabit on a daily basis has generated an interesting and authentic process of user participation in the construction of a programme for the use of these places.

The establishment of an investigative committee during the preparation phase, composed of researchers from different disciplinary fields, provided an opportunity to imagine WeDarch in an interdisciplinary key, in which the various disciplines fundamental to the training of architects – from Architectural Design to Urban Design, History, technology and restoration – contributed to defining the general intervention strategies within which the design experimentation would take place.

This was achieved by setting up lectures and seminars aimed at exploring different thematic aspects, with the aim of increasing interaction between students and teachers, giving the different disciplines an active role in the construction of intensive experimentation.

__________________________________________________________________________________________

Forme sperimentali di erogazione didattica intensiva: il LaboratorioWeDARCH

Il Laboratorio WeDarch rappresenta una esperienza sperimentale di didattica intensiva immaginata come alternativa alla forma tradizionale del Laboratorio di Progettazione Architettonica e Urbana erogato secondo il modello previsto Decreto Ministeriale del 24 febbraio 1993.

Come luogo per la sperimentazione è stato scelto la Città Universitaria di Palermo, un’area estesa, attraversata da un sistema vegetale profondo, che dalla periferia esterna penetra sino al bordo del centro storico, e serrata da quartieri fortemente urbanizzati. Enclave recintata, essa si presenta come un’“isola” senza troppe relazioni con la città circostante. L’origine di tale condizione è dovuta alla adesione al modello dei campus intesi come sistemi chiusi ed autosufficienti; alla sua collocazione in un’area originariamente esterna alla città, e oggi raggiunta dalla urbanizzazione di fine Novecento; da una sottovalutazione del ruolo delle infrastrutture nella vita di questi sistemi insediativi, che ha d’altra parte caratterizzato le scelte di politica urbana palermitana degli ultimi cinquanta anni.

Tra gli obiettivi posti alla base delle attività progettuali del Laboratorio WeDARCH vi sono stati lo studio di due aspetti generali: uno di carattere urbano e delle connessioni tra campus e città; l’altro legato al funzionamento interno della cittadella, ai suoi spazi aperti e di comunità, alla sua mobilità interna e alla possibilità di introdurre funzioni nuove sia per la didattica che per la vita sociale della comunità.

I progetti pertanto hanno espresso l’intenzione di incrementare il grado di porosità della città universitaria lavorando su un articolato sistema di relazioni trasversali. Ci si è posto l’obbiettivo di definire i suoi bordi, in cui il campus si interfaccia coi quartieri urbani residenziali circostanti e con le mura occidentali della città storica; di implementare il ruolo del sistema vegetale continuo di Parco Cassarà-Fossa della Garofala-Giardino d’Orleans; di rafforzare le relazioni a distanza con il sistema dei vicini ospedali Civico e Policlinico, nonché con la valle dell’Oreto.

La riduzione della mobilità carrabile e dei suoli artificiali, l’implementazione delle materie vegetali e il disegno di giardini e l’introduzione di funzioni di servizi aggiuntive a quelle della formazione, hanno trovato nella progettazione di aule-agorà all’aperto il focus con cui declinare il tema della didattica en plen air e l’utilizzo pubblico e collettivo dello spazio aperto anche per attività culturali e del tempo libero. Infine, l’obiettivo di coinvolgere gli studenti nella progettazione degli spazi e dei luoghi da essi abitati quotidianamente ha generato un interessante, quanto autentico, processo di partecipazione degli utenti alla costruzione di un programma d’uso di questi luoghi.