Luigiemanuele Amabile in conversation with Maria Conen.

Knowing a place, before delving into the complex process of designing architecture, represents one of the first fundamental acts that architects should indulge in. For Maria Conen, observation is a layered practice in which the existing conditions of a place are approached with equal attention, allowing different realities to surface without being ranked or simplified. Her teaching trains students to recognise these overlapping situations through photography, research, close reading and dialogue, treating context as an active field that participates in shaping the project. From this position, form arises from what is encountered rather than being imposed, and the studio becomes a shared environment in which ways of looking are collectively built. The result is a pedagogy that links academic work and professional practice through a sustained exercise in attentiveness, where design emerges from what precedes it rather than from predetermined intentions.

LA: To begin: could you describe how you typically organize your design studio? Are there particular characteristics of your approach that you consider specific to the ETH context – or to your own architectural vision – when compared to other institutions?

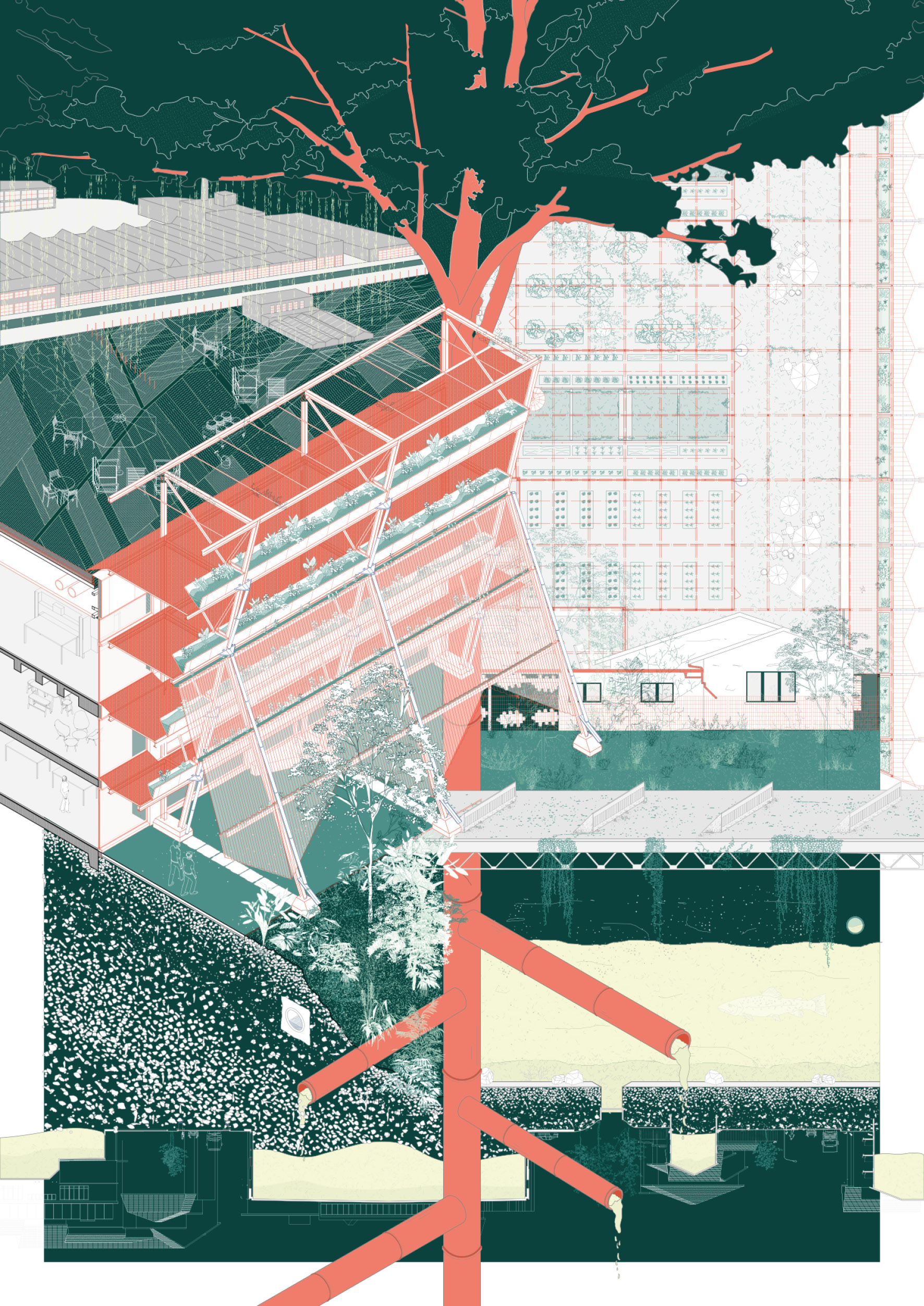

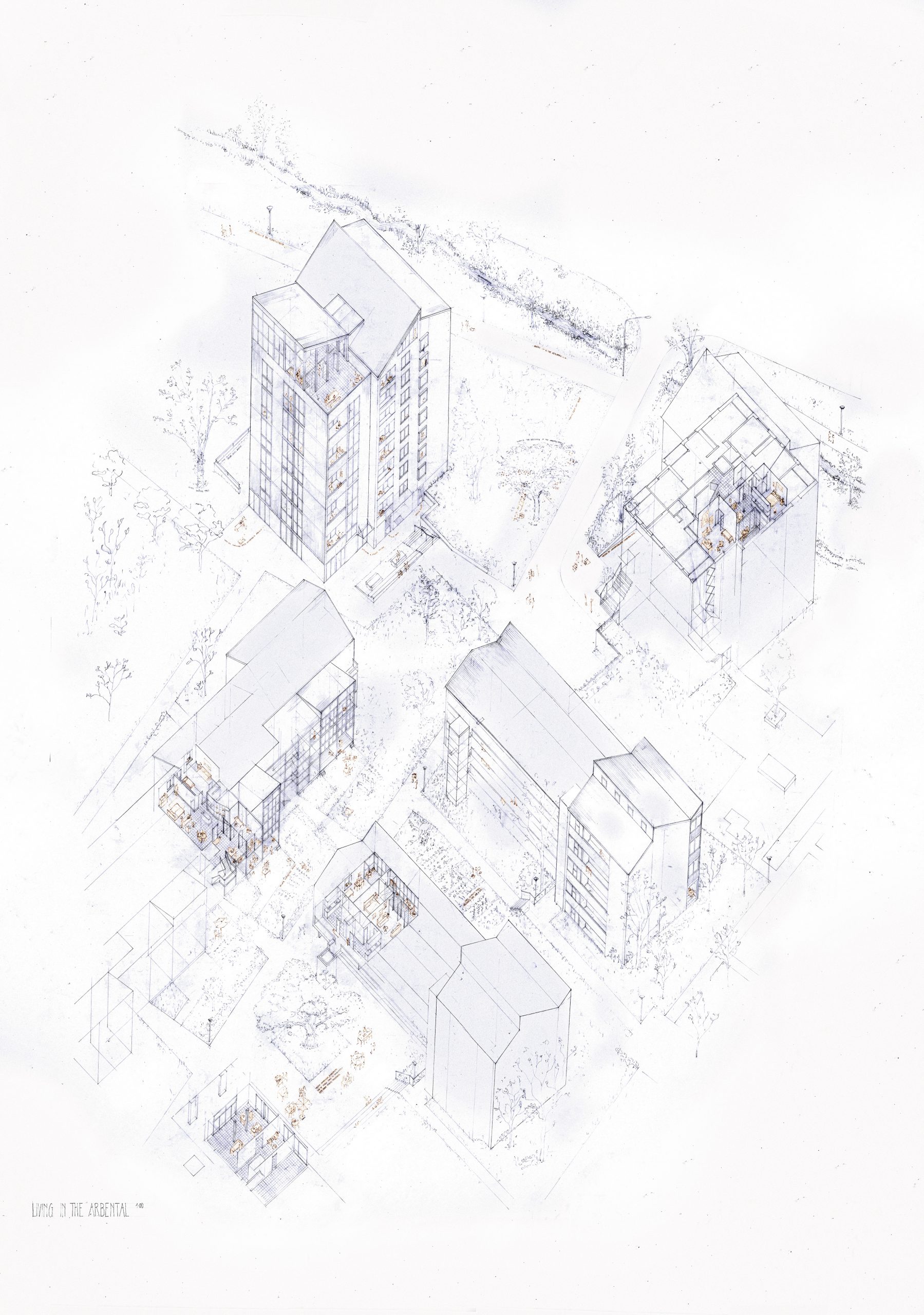

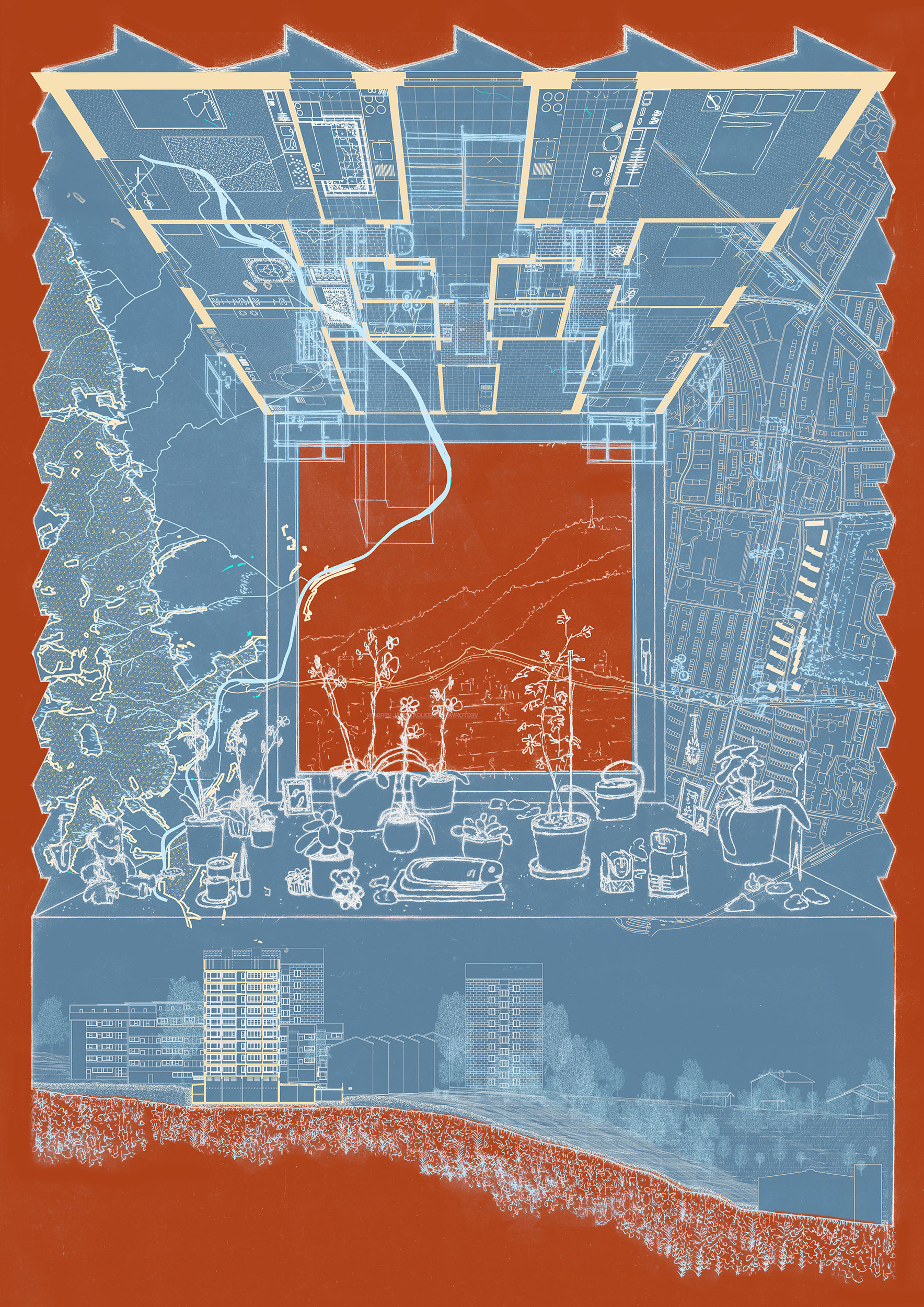

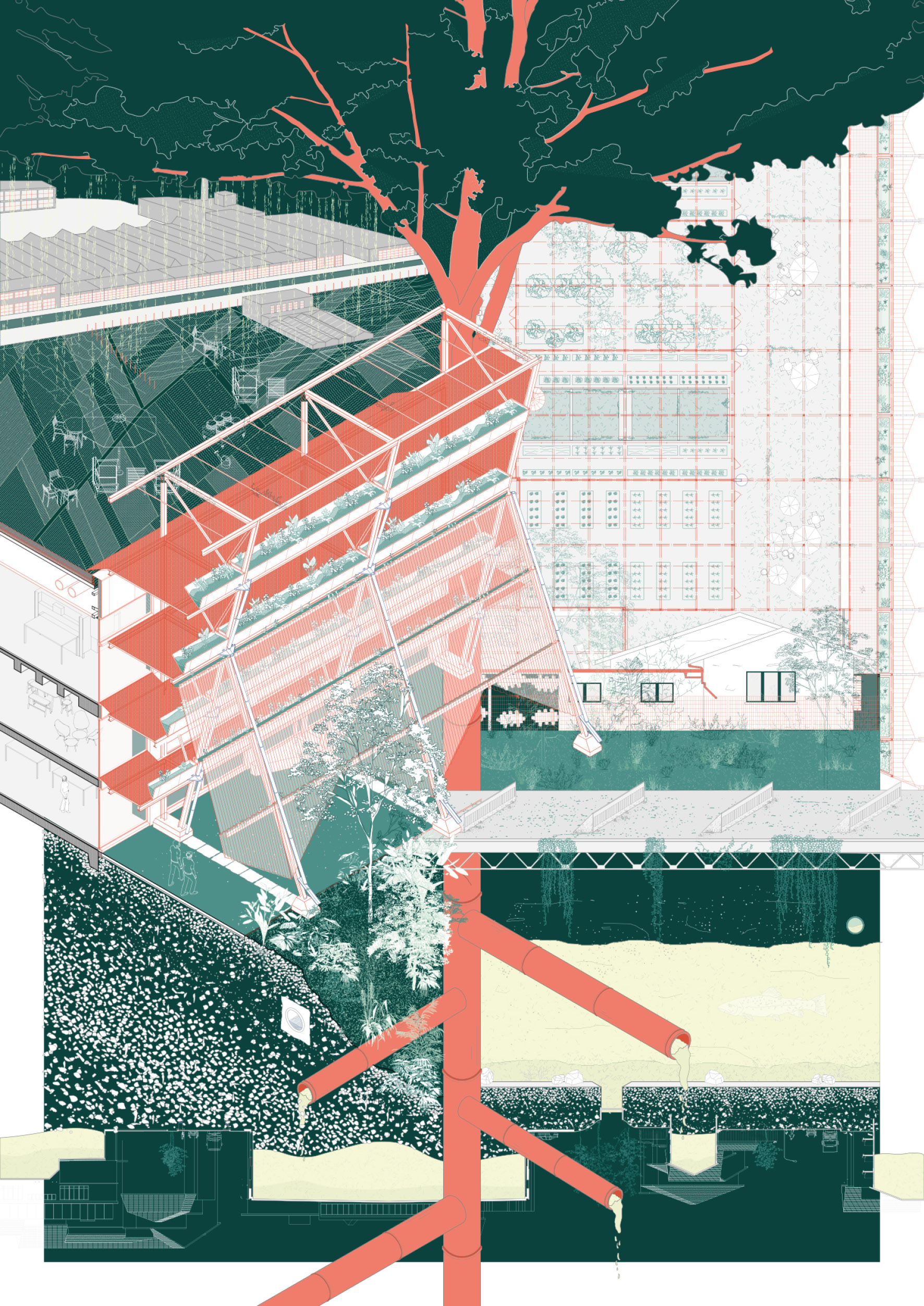

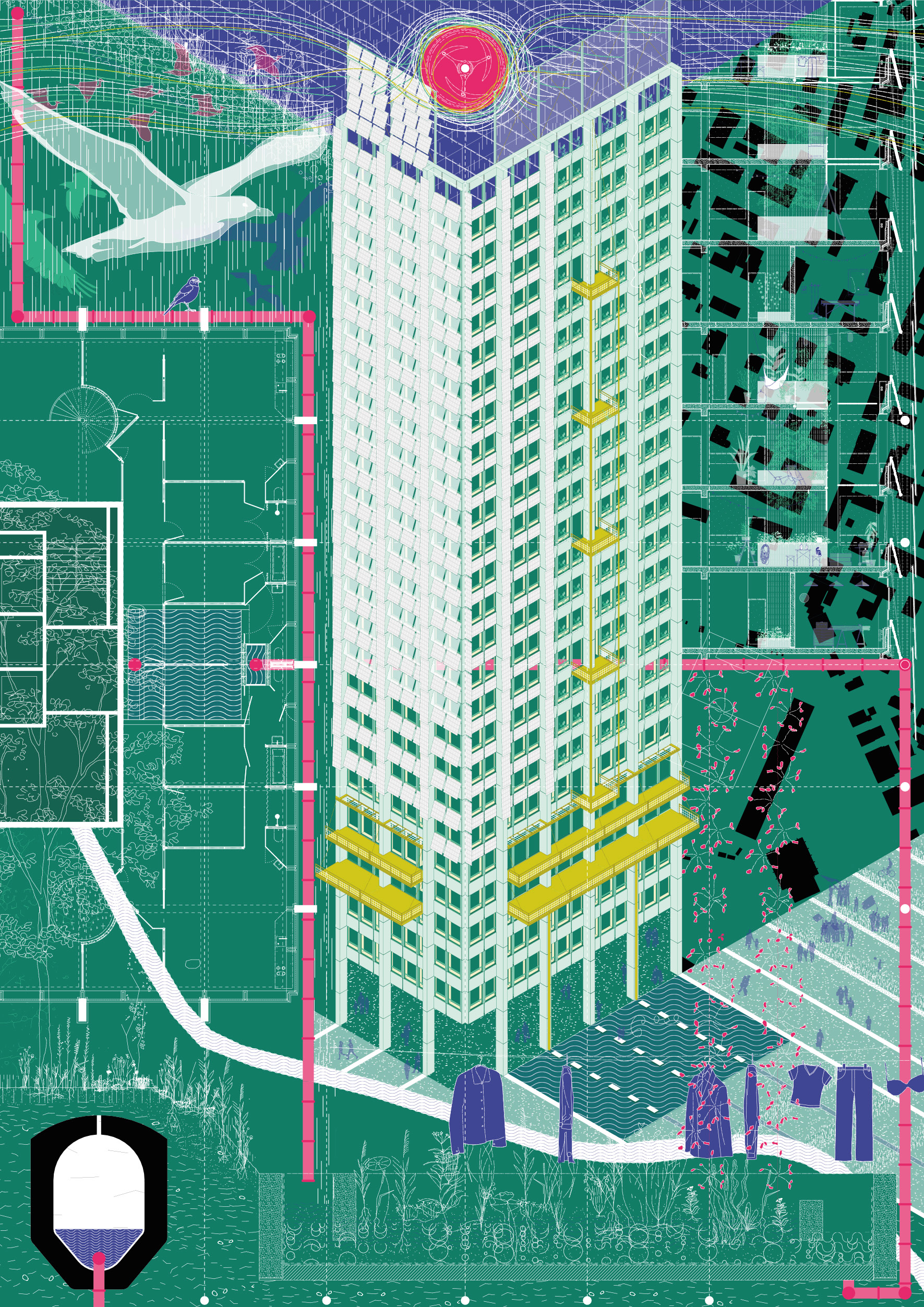

MC: I can say that the teaching is not really influenced by the place where we teach. It’s really something that comes from a deep interest we have in architecture – and also in the whole environment we live in. That’s how we approach teaching: it’s always about thinking in a very holistic way about the project. So it’s not only about the object – it’s really about everything around it too. I’d say that’s not linked to the university; it’s also something we do in the office. The work we do in the office is, in that sense, very much linked to the vision – or perhaps the attitude – that we try to teach. Maybe it’s an attitude of understanding the site before starting the project. So, in that sense, I can just talk about the teaching – and I’d say that, in recent years, it always revolves around both existing structures and contexts. By contexts I mean: the soil, the plants, the trees, the animals and the inhabitants – everything that is already on site – and all of it is as important as the built structure. So we always look at things through multiple layers, not just the layer of the constructed world that we usually look at in architecture. I’d say something very important in our teaching is this layering of elements, which we try to analyze at the beginning of the project. It’s what we call “Ways of Looking”.

LA: I found it really interesting that you used the word “attitude” or “behavior”, in the Italian academic context – and this reflects my own education – architectural pedagogy has long been shaped by traditions emphasizing form-making, typology, the role of the city and the authority of architectural knowledge. In contrast, your description seems to point toward a more interpretive, responsive mode of engagement. So I’d like to ask: do you think the architect’s knowledge of form – the ability to shape and manipulate form – is still central today? Or should we begin to question and perhaps decenter that kind of authorship in favor of other priorities?

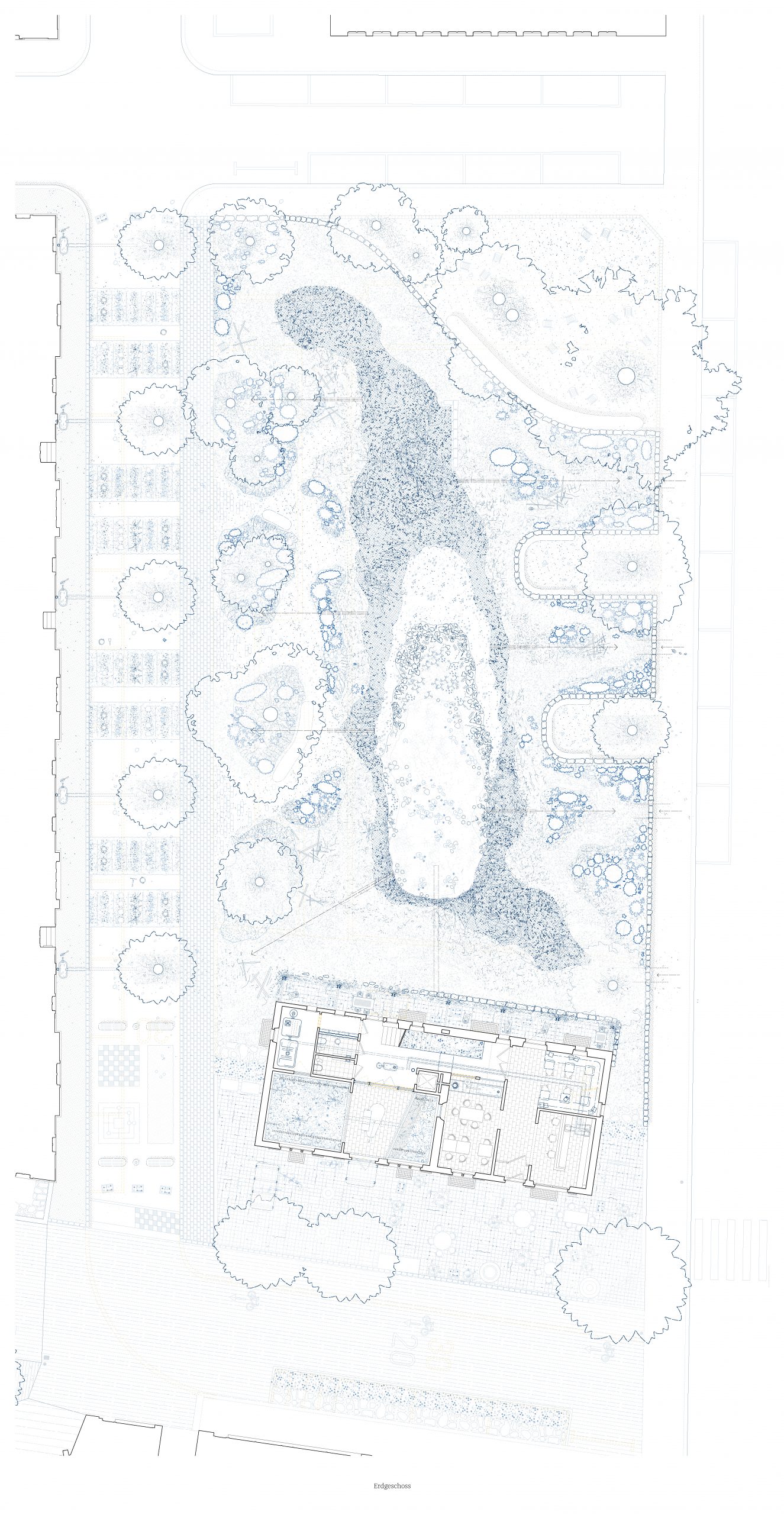

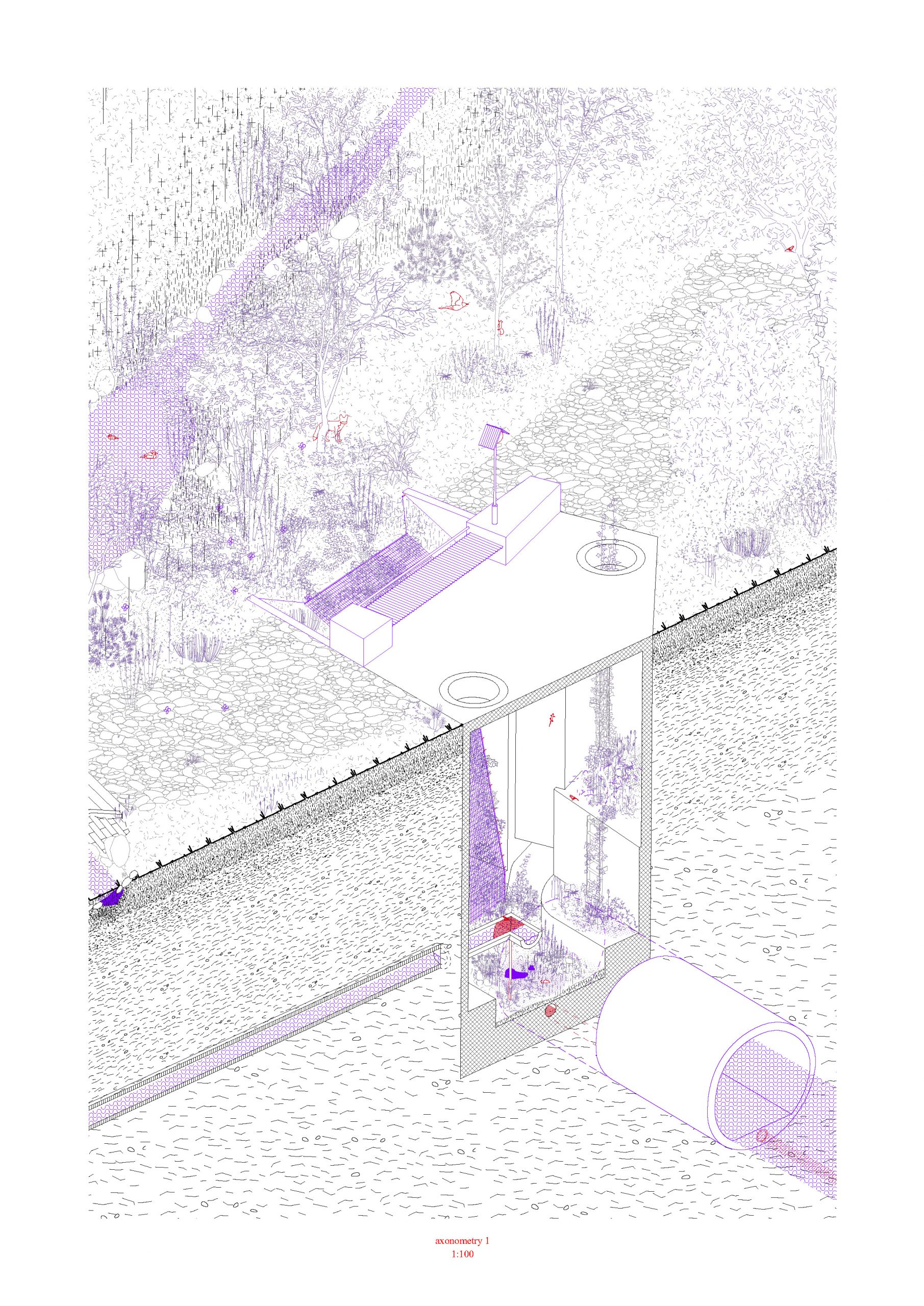

MC: I think space remains fundamental – creating and shaping space is how we live. It’s about protection, feeling at home and creating atmosphere. I was also very influenced by Aldo Rossi and that strong way of looking at form and his belief that form could solve everything. I still think form is important – but form should really react to what’s already there on site. An overly formalistic approach often overlooks what already exists. It assumes that you arrive somewhere and impose your vision. I think we can’t and shouldn’t work that way anymore, because so much is already here. We need to continue these stories. Often there’s already quality in those spaces – sometimes hidden. That’s why it’s essential to understand the context. Maybe the generation before mine would say, “concept before context”. But for me, it’s the opposite. Especially with the ecological questions, the biodiversity crisis, species loss… we can’t just arrive, do something, and leave again. That’s too easy… And this complexity we face today – we can’t solve it with purely formal tools. Form is important and it can be the most beautiful part of the design process – but it arrives after the reading of the context. The buildings we design are often meant to stay for a very long time – therefore it’s important to be thoughtful about the design and construction. But I wouldn’t separate so strictly anymore between inside and outside. I’m very interested – as I said – in the exterior being as important as the interior. And by exterior, I don’t just mean the line that separates inside and outside – the façade – I mean the outdoor spaces and their relationship to the building. When you start thinking this way, you also have to ask: how important is the building itself? Because you build not only into the earth but into the world’s fabric – its materials, ecologies, and human networks – and in the end, the building is only a small part of that. So where do you put the focus? What are the most important things to take into account? If you only think from a formal point of view, you are centering everything around the human being standing in front of the building. But in today’s globalized world, we can’t think like that anymore. There are too many other layers involved. Materials come from somewhere; they carry footprints, they affect not just your site but the entire ecosystem. That’s the fundamental difference, I’d say, from a purely object-based way of thinking about architecture.

LA: From what you describe, it seems that you encourage students to engage with complexity – to work across multiple layers of observation and analysis. Could you explain how you introduce this in the early phases of the studio? Do you have specific methods or pedagogical tools to help students develop a critical understanding of context – beyond the purely physical?

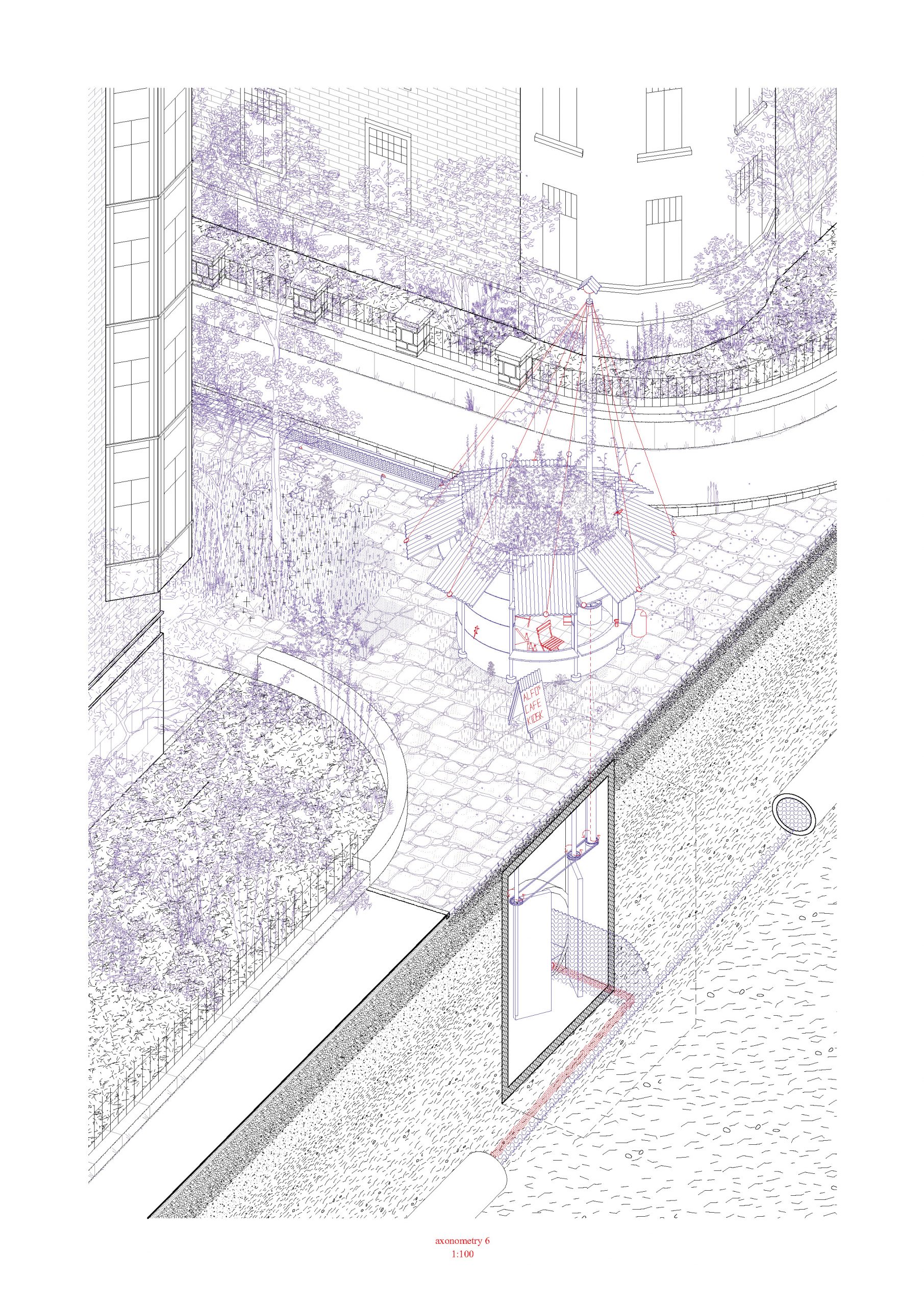

MC: Yes – the idea of “ways of looking” is always present in the first phase of the project. We always start by asking, how should we look at the site to understand its different layers? We work a lot with photography – because I think it’s a great way to capture an existing context. It allows for personal interpretation. Each photograph can express your own way of seeing– not just a quick snapshot, but a deliberate act: how do you frame something? How close do you go? How bright or dark is the picture? What do you include or exclude in your frame? We often ask students to take two photographs of the site – one that speaks to the architecture and one that relates to the broader context. These two become the starting point for discussion. This is complemented by material from archives, interviews with local people, and also with three main lenses: the sociological (who’s there, how they live), the ecological (what plants, animals, species are present), and the political-economic dimension (what forces shape the site and its uses). That’s how we start the project. Then – depending on the semester – we add a fourth layer: references from architecture. For instance, in the last two semesters, we worked on the theme of “In and Out.” It focused on the section and the threshold between interior and exterior – what does the façade do? How open or closed is it? What happens at ground level, where the building meets the earth? The students had to draw a section from an existing housing project. That became the first way of entering the topic. Interestingly, many of them brought questions from that section analysis into their own projects – even if they were working with a different site. That’s how we do the analysis, and it plays a fundamental role in the studio. Then you begin to talk about space, about form, and so on – but these grow naturally from everything that came before.

LA: The way you approach “context” is particularly rich – not as a static backdrop but as something layered and active. In fact, we could say that we no longer speak of a single “context”, but of many. Each project might engage environmental, social, political, and historical dimensions, all perceived differently by those who inhabit them. In this light, I’d like to ask about the relationship between your academic teaching and professional practice. You are a partner in a well-known office in Zurich. Do you structure your design studios similarly to how you work in the office? Or do you apply what you learn in the academic context to your practice? Is there a reciprocal influence between these two domains?

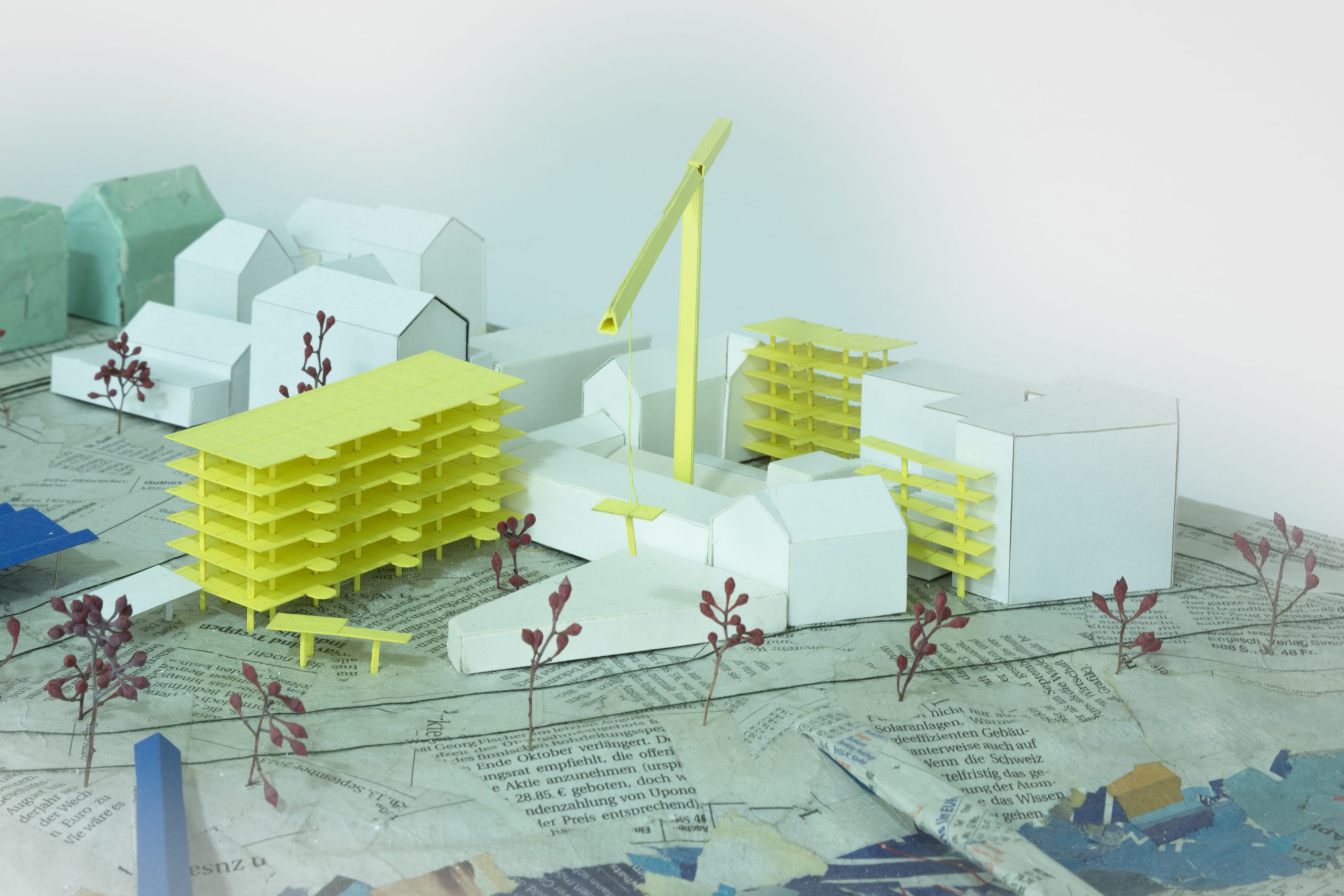

MC: Yes, my partner, Raoul Sigl, and I used to teach together, and teaching and practice are very linked. In the office, projects last five to ten years; at school, only 14 weeks. So the depth and rhythm are completely different. In the office, we often hit limits – regulations, clients, costs – that can restrict experimentation and innovation. At the university, we have more freedom and access to researchers from many fields – engineers, ecologists, urban theorists and sociologists. We collaborate, learn, and explore perspectives we couldn’t in practice. In return, these discoveries feed back into the practice…

LA: Your mention of clients and competitions makes me think of the difficult realities many young architects face after graduation. In your view, how can emerging students-practitioners develop the critical awareness to choose which projects or clients to accept – especially at the beginning of their careers, when opportunities may be limited? What strategies or forms of ethical positioning would you recommend to young architects trying to remain true to their values?

MC: In Switzerland, we have a very open competition system – young offices can enter competitions and shape their own path. But it’s still not an easy path to follow. In that sense, teaching critical thinking is an important part of my work at ETH: be proactive, but stay critical. Question things. Choose consciously where you work and with whom you collaborate.

LA: In Italy, architectural education still places a strong emphasis on the disciplinary identity of architecture as a civic art – and on its compositional dimension. We don’t typically speak of “architectural design” as in Anglo-American contexts, but rather of architectural composition. This reflects a certain cultural continuity and an idea of architecture that is at once artistic, formal, and civic. What is your view on the relevance of “composition” today? Does the idea of architectural composition still have meaning in a context where reuse, transformation, and adaptation often replace invention?

MC: I still talk a lot about composition and proportion. When it comes to reusing elements, such as windows, doors, and fragments from other buildings, it’s all about how things fit together. However, this is not about starting from scratch, as in the Beaux-Arts tradition. It’s about creating something new with what’s already there – often in a less formal way and guided by the existing context. Reuse also demands a deep understanding of the elements of architecture: what is a column? What does it mean spatially to place a pillar? How does it relate to a beam? These questions remain central – just approached differently. Ultimately, construction is always about combining materials in meaningful ways, and this still matters. In our office and studio, we constantly discuss composition in terms of space, urban relationships and materials. At the same time, we are rethinking elements of architecture. Is a staircase still a meaningful architectural feature? Or has it become an exclusive feature, inaccessible to many? We need alternatives. Take the step as a threshold, for example – once a symbol of transition, it now poses accessibility issues. We are rethinking how buildings interface with the public realm. Some elements evolve, while others – such as the column – remain unchanged. I still admire Palladio’s villas. In Villa Cornaro, for example, four columns do not touch the wall yet still define the entire room. No furniture is needed – the columns create the space. These references still have much to teach us. The key is to avoid copying them blindly. Learn from them and reinterpret them. That’s what I believe.

LA: You mentioned earlier the increasing importance of working with reused materials and existing elements. Do you see this as a return to questions of proportion, jointing, tectonics – in short, composition – but approached through different means? And if so, how does that influence the way you frame the studio projects?

MC: No, it shouldn’t be fixed. We usually work in existing structures, so something is already there – and that’s very different from starting with a blank page. We’ve done new-build projects in studio as well, but when, for example, we work on housing, you already think about what it means to live in an apartment – and what it means to live in its surrounding context. You work at both levels. I can’t say we move from large scale to small scale – it’s more of a mix. The layering I mentioned earlier helps students work at different scales at the same time: developing spatial ideas while also dealing with broader themes. That process eventually forms a vision. I have also seen other studios start from one-to-one elements and build outward – that works too. Personally, I tend to begin from stories we find on site and carry those into the architecture. That story might start with a detail – a one-to-one element – or with something else entirely: a calculation, a material, an encounter. I don’t follow one doctrine.

LA: Maybe just a last quick question. It seems that you give a lot of space for students to bring in their own references, to build their own layers of knowledge and reach their own final design. How important is this freedom? How do you think it relates to the collective structure of the design studio? In other words: how do students bring their personal trajectory into a shared space?

MC: That’s a good and complicated question. I would say – and I want to be precise here – being a good teacher means having a real conversation with your students. You guide them, but you also let them follow your line of thought. It’s not about saying “this is right” or “this is wrong”. It’s about dialogue – explaining your position, repeating that discussion. In that sense, it’s not completely free. Not everything is possible. Even in the references we choose – for example, the photographers we ask students to study – we set a very specific framework. We say: take photographs in the spirit of this particular photographer, because we believe it’s a productive way to learn how to frame and observe. It’s a big internal discussion before every semester to select the references. The same goes for choosing the site; that already reflects a specific attitude we want to transmit. We also give lectures, short workshops, and invite guests. In the end, we’re building a kind of environment – a space – and within that space, students can move, swim, navigate, find their own position. And then, through weekly discussions, we draw together, reflect together. That’s how students develop their projects and their own way of thinking. They start to understand the reasons behind their decisions. It’s a shared process involving the whole teaching team. We spend a lot of time thinking about the students’ projects. I think that’s part of the responsibility of a good teaching team: to take time and support students throughout their journey. They should understand the reasons behind what they are doing. Of course, some students find their own path more quickly, and you just guide them a little. Every student is different – in their abilities, their timing, their process – and you have to work with that. It’s a way of communicating and building trust. In the end, students should be able to stand by their project and explain it clearly – that’s when you really learn critical thinking, which is another key idea we emphasize in the studio. It’s about finding your own voice. There’s a wonderful book by bell hooks called Teaching Critical Thinking – it’s one of my favourites. It covers everything: how to teach, how to respond, how to resist. I found it deeply impressive.

LA: Throughout our conversation, what struck me is how often metaphors of voice and conversation emerged – dialogue among students, within your team, with the site, and with architectural history. It seems that dialogue itself is central to your approach, both in education and in practice.

MC: Exactly, yes – that’s very true.

___________________________________________________________________________________________

Stratificare contesti

Luigiemanuele Amabile in conversation with Maria Conen.

Conoscere i luoghi, prima di entrare nel vivo dell’atto del progettare, rappresenta una delle prime azioni fondamentali che l’architetto compie. Per Maria Conen, l’osservazione rappresenta una pratica stratificata in cui le condizioni dei luoghi vengono affrontate tutte con la stessa attenzione, lasciando emergere possibili configurazioni derivanti non da gerarchie quanto da questioni tangibili. La sua didattica invita gli studenti a riconoscere queste sovrapposizioni attraverso la fotografia, la ricerca, la lettura ravvicinata e il dialogo, considerando i contesti come un campo attivo che contribuisce alla realizzazione del progetto. In questo processo, la forma emerge da ciò che si incontra, anziché essere imposta, e il laboratorio di progettazione diventa uno spazio condiviso in cui gli sguardi si allenano e costruiscono collettivamente. Ne deriva una pedagogia che si configura come un esercizio continuo di attenzione, in cui il progetto si fonda su ciò che lo precede e non su intenzioni precostituite.

LA: Come organizzi solitamente il tuo laboratorio di progettazione? Ci sono aspetti del tuo approccio che ritieni siano specifici del contesto dell’ETH di Zurigo o che siano più direttamente riconducibili al tuo modo di concepire il progetto rispetto a quello di altre scuole?

MC: Penso che l’insegnamento del progetto non sia realmente influenzato dalla sede in cui si insegna. Piuttosto, il progetto viene strutturato a partire da un interesse profondo che nutriamo per l’architettura e, più in generale, per l’ambiente in cui viviamo. Questo è il nostro approccio alla didattica: cerchiamo sempre di pensare al progetto in modo olistico. Non ci interessa solo il risultato finale, ma anche tutto ciò che lo circonda. Questo metodo di lavoro non è legato soltanto all’insegnamento universitario, ma è qualcosa che pratichiamo anche nella nostra attività professionale. In ufficio, ciò che portiamo avanti è strettamente connesso alla visione, o forse all’attitudine e al comportamento che cerchiamo di trasmettere nell’insegnamento: un processo che prevede la conoscenza e la comprensione del sito prima di avviare qualunque ragionamento progettuale. In questo senso, negli ultimi anni, la nostra didattica ruota sempre attorno alle strutture esistenti e ai contesti stratificati. Per “contesti” intendo tutto ciò che è già presente sul sito e che ha la stessa importanza della struttura in progetto. Guardiamo quindi alle cose attraverso più strati, più layer, non soltanto attraverso la lente dell’ambiente costruito, che solitamente domina lo sguardo architettonico. Un aspetto centrale del nostro insegnamento è proprio questa stratificazione degli elementi che cerchiamo di analizzare all’inizio del progetto. È ciò che chiamiamo “Ways of Looking”.

LA: Trovo particolarmente interessanti i termini “attitudine” e “comportamento” che usi. Nel contesto accademico italiano, la pedagogia del progetto di architettura è stata a lungo influenzata da tradizioni che enfatizzano il ragionamento sulla forma, sul tipo e sul ruolo delle questioni urbane e del progetto della città, nonché sul ruolo dell’architetto nella costruzione della cultura urbana. La tua descrizione sembra invece orientarsi verso una modalità di relazione più interpretativa e reattiva. Alla luce di ciò, pensi che la conoscenza delle questioni formali da parte dell’architetto, intesa come capacità di modellare e manipolare la forma, sia ancora centrale oggi o ritieni che sia necessario iniziare a metterne in discussione la centralità, decentrando questo tipo di capacità a favore di altre priorità?

MC: Ritengo che la questione dello spazio resti fondamentale, in quanto la sua creazione e modellazione influisce sul modo in cui viviamo. È importante capire come sentirsi protetti e come creare un’atmosfera specifica. Sono stata fortemente influenzata da Aldo Rossi e dal suo modo di concepire la forma, nonché dalla sua convinzione che la forma potesse risolvere molte questioni. Continuo a pensare che gli aspetti formali siano importanti, ma devono interagire con ciò che è già presente sul sito. Un approccio eccessivamente formalistico tende spesso a trascurare ciò che esiste già, presupponendo di arrivare in un luogo e imporre la propria visione. Oggi non è più possibile né auspicabile lavorare in questo modo, perché esiste già molto e bisogna lavorare in continuità con le storie già in atto. Nei luoghi esistono spesso qualità nascoste ed è per questo che comprendere il contesto diventa essenziale. Forse la generazione che mi ha preceduto avrebbe detto concetto prima di contesto, ma per me è l’opposto. Alla luce delle questioni ecologiche, della crisi della biodiversità e della perdita di specie, non possiamo più limitarci a intervenire e poi abbandonare i luoghi a se stessi. La complessità che ci troviamo ad affrontare oggi non può essere risolta con strumenti esclusivamente formali. La forma è importante e può rappresentare l’aspetto più interessante del processo progettuale, ma arriva solo dopo aver compreso i contesti. Gli edifici che progettiamo sono destinati a durare a lungo, pertanto è necessario prestare attenzione sia al processo che alla costruzione. Non mi interessa separare l’interno dall’esterno, ma lavorare affinché abbiano la stessa importanza. Per “esterno” non intendo solo il confine tra l’interno e l’esterno (la facciata), ma anche gli spazi aperti e la loro relazione con l’edificio. Quando si inizia a ragionare in questi termini, diventa inevitabile interrogarsi anche sull’importanza dell’edificio in sé, perché costruire significa intervenire non solo sul suolo, ma anche sul tessuto del mondo, fatto di materiali, ecosistemi e reti sociali. Alla fine, l’edificio rappresenta solo una piccola parte di questo insieme. Dove si colloca allora il fulcro del progetto e quali sono gli aspetti realmente prioritari? Se si ragiona esclusivamente dal punto di vista formale, si tende a concentrarsi esclusivamente sull’impatto visivo dell’edificio, ma nel mondo globalizzato di oggi non è più possibile ragionare in questi termini, perché le stratificazioni coinvolte sono molteplici. I materiali provengono da luoghi specifici, portano con sé delle impronte e producono effetti che non riguardano solo il sito, ma l’intero ecosistema. Questa, a mio avviso, è la differenza fondamentale rispetto a un modo di pensare l’architettura come puro oggetto.

LA: Questo processo sembra incoraggiare gli studenti a confrontarsi con la complessità, lavorando su più livelli di osservazione e analisi. Potresti illustrare come introduci questo approccio nelle fasi iniziali del laboratorio? Utilizzi metodi o strumenti specifici per aiutare gli studenti a sviluppare una comprensione critica del contesto che vada oltre la sua dimensione puramente fisica?

MC: Sì, l’idea dei “ways of looking” è sempre presente a partire dalle prime fasi del progetto. Iniziamo sempre chiedendoci come osservare il sito per comprenderne i diversi strati. Lavoriamo molto con la fotografia perché la consideriamo uno strumento eccellente per cogliere alcune condizioni dei contesti esistenti e perché consente un’interpretazione personale. Ogni fotografia può esprimere un modo di vedere proprio, non come uno scatto rapido, ma come un atto deliberato: come inquadrare qualcosa, quanto avvicinarsi, quanto l’immagine deve essere luminosa o scura, cosa includere o escludere dal campo visivo. Di solito chiediamo agli studenti di realizzare due fotografie del sito: una che parli dell’architettura e una che si riferisca a un contesto più ampio. Queste fotografie diventano il punto di partenza della discussione. A questi si affiancano materiali d’archivio, interviste agli abitanti e tre approfondimenti specifici: quello sociologico, che riguarda chi c’è e come vive; quello ecologico, che considera le presenze vegetali e animali; e quello politico-economico, che indaga le forze che modellano il sito e i suoi usi. È da qui che parte il progetto. Successivamente, in base al semestre, aggiungiamo ulteriori livelli di approfondimento costituiti da riferimenti architettonici. Ad esempio, negli ultimi due semestri abbiamo lavorato sul tema “In and Out”, concentrandoci sulla sezione e sulla soglia tra interno ed esterno: cosa fa la facciata, quanto è aperta o chiusa e cosa accade al piano terra nel punto in cui l’edificio incontra il suolo. È stato chiesto agli studenti di disegnare una sezione di un progetto residenziale esistente e questo è diventato il primo modo per affrontare il tema. In modo interessante, molti di loro hanno poi tradotto le questioni emerse da quell’analisi della sezione nei propri progetti, anche se occupati su siti diversi. Questo è il modo in cui svolgiamo l’analisi e il suo ruolo nel laboratorio è fondamentale. Solo successivamente si comincia a parlare di spazio, forma e così via, ma questi aspetti crescono in modo incrementale a partire da tutto ciò che li ha preceduti.

LA: Da quanto descritto, il concetto di contesto assume un significato piuttosto diversificato. Non viene considerato come uno sfondo statico, ma come uno spazio stratificato e dinamico, tanto che non si parla più di un singolo contesto, ma di molti contesti intrecciati tra loro. Ogni progetto può coinvolgere dimensioni ambientali, sociali, politiche e storiche percepite singolarmente dai vari abitanti. In quest’ottica, vorrei chiederti del rapporto tra la tua attività accademica e la tua pratica professionale. Strutturi i tuoi laboratori di progettazione nello stesso modo in cui lavori nel tuo studio? Oppure ciò che impari nel contesto accademico lo applichi alla pratica professionale? C’è un’influenza reciproca tra questi due ambiti?

MC: Sì, io e il mio partner, Raoul Sigl, abbiamo spesso insegnato insieme. La nostra attività didattica e la nostra pratica professionale sono strettamente connesse. In ufficio, i progetti vanno avanti per cinque-dieci anni, mentre a scuola durano solo 14 settimane. Quindi, il ragionamento e il ritmo sono completamente diversi. In ufficio, spesso ci confrontiamo con una serie di limiti – regolamenti, clienti, costi – che possono rendere sterili alcuni aspetti della sperimentazione e dell’innovazione. All’università, invece, ci muoviamo con maggiore libertà e ci confrontiamo con ricercatori di vari ambiti: ingegneri, ecologisti, urbanisti e sociologi. Collaboriamo, impariamo e esploriamo prospettive che non potremmo avere nella pratica. Queste scoperte, poi, si riflettono nel nostro lavoro in studio.

LA: Il riferimento che fai a clienti e concorsi richiama le difficili condizioni che molti giovani architetti si trovano ad affrontare dopo la laurea. Dal tuo punto di vista, come possono gli studenti e i giovani professionisti sviluppare una consapevolezza critica che li aiuti a scegliere i progetti e i clienti da accettare, soprattutto nelle fasi iniziali della carriera, quando le opportunità sono limitate? Quali strategie o forme di posizionamento etico suggeriresti a chi cerca di rimanere fedele ai propri valori?

MC: In Svizzera esiste un sistema di concorsi molto aperto che consente anche agli studi giovani di partecipare e di costruirsi un percorso. Nonostante ciò, non è comunque una strada semplice. In questo senso, insegnare il pensiero critico è una parte importante del mio lavoro all’ETH: bisogna essere propositivi, ma anche critici. Mettere in discussione le cose. Scegliere consapevolmente dove lavorare e con chi collaborare.

LA: In Italia, la formazione architettonica continua a insistere con forza sull’identità disciplinare dell’architettura come arte civica e sulla sua dimensione compositiva. Non si parla di architectural design, come nei contesti anglo-americani, ma piuttosto di composizione architettonica, espressione di una continuità culturale e di un’idea di architettura che unisce volontà artistica, ricerca formale e impegno civico. Qual è, a tuo avviso, l’importanza del concetto di composizione oggi? In un contesto in cui l’invenzione non è più la priorità, ma il riuso, la trasformazione e l’adattamento sono i veri protagonisti, come può evolvere la composizione architettonica?

MC: Continuo a parlare molto di composizione e proporzione. Quando si tratta di riutilizzare elementi come finestre, porte o frammenti provenienti da altri edifici, la questione riguarda il modo in cui le varie parti si assemblano tra loro. Tuttavia, non si tratta di ripartire da una tabula rasa, come nella tradizione dei Beaux-Arts, ma di creare qualcosa di nuovo a partire da ciò che già esiste, lasciandosi guidare dal contesto più che dalla ricerca di una configurazione formale specifica. Il riuso richiede anche una profonda conoscenza degli elementi architettonici: che cos’è una colonna, cosa significa collocare spazialmente un pilastro e come si relazionano le travi. Queste questioni restano centrali, ma vengono affrontate in modo diverso. In definitiva, costruire significa sempre combinare i materiali in modo che essi determinino nuovi significati. Nel mio studio e nel laboratorio che dirigo, discutiamo costantemente di composizione in termini di spazio, relazioni urbane e materiali. Allo stesso tempo, proviamo a ripensare alcuni elementi dell’architettura. Una scala è ancora un elemento significativo o si è trasformata in una soluzione architettonica esclusiva e inaccessibile per molti? Sono necessarie delle alternative. Basti pensare ai gradini, che spesso fungono da soglia e che, sebbene un tempo simboleggiasse il passaggio, oggi pone problemi di accessibilità. Dobbiamo ripensare il modo in cui gli edifici si relazionano con lo spazio pubblico. Alcuni elementi evolvono, mentre altri, come la colonna, per esempio, restano invariati. Continuo ad ammirare le ville di Palladio. A Villa Cornaro, per esempio, quattro colonne non toccano la parete, eppure definiscono l’intero ambiente. Non servono arredi: sono gli elementi verticali a costruire lo spazio. Questi riferimenti hanno ancora molto da insegnarci. La chiave è non copiarli in modo acritico, ma imparare da essi e reinterpretarli. Questo è ciò in cui credo.

LA: In precedenza hai accennato all’importanza crescente del lavoro con materiali riutilizzati ed elementi esistenti. Vedi in questo un ritorno alle questioni legate alle proporzioni, alla consonanza tra i materiali e alla tettonica, in altre parole alla loro composizione, ma affrontate con strumenti e modalità contemporanee? In tal caso, in che modo questo orientamento incide sull’impostazione dei progetti di laboratorio?

MC: No, non credo, è qualcosa di diverso. Lavoriamo spesso all’interno di strutture esistenti e questo ci permette di confrontarci con qualcosa di già esistente, cosa molto diversa dal partire da una pagina bianca. Abbiamo affrontato anche progetti di nuova costruzione in laboratorio, ma quando, per esempio, lavoriamo sull’abitare, riflettiamo immediatamente su cosa significhi vivere in un appartamento nel contesto che lo circonda, operando su entrambi i livelli contemporaneamente. Non direi che si procede dal più grande al più piccolo, ma piuttosto si tratta di una combinazione di entrambi. La stratificazione di cui parlavo prima aiuta gli studenti a lavorare su varie scale contemporaneamente, sviluppando idee legate allo spazio e, allo stesso tempo, confrontandosi con temi più ampi. Questo processo finisce per costruire una visione. Altri laboratori partono da elementi in scala 1:1 e sviluppano il progetto a partire da essi, e questo metodo funziona altrettanto bene. Personalmente, tendo a iniziare dalle storie che recuperiamo dal sito e a inserirle nell’architettura. Queste storie possono partire da un dettaglio, da un elemento in scala 1:1 o da qualcosa di completamente inaspettato, come un calcolo strutturale, un materiale o un incontro fortuito. Non seguo una sola dottrina.

LA: Un’ultima domanda. Sembra che nel tuo laboratorio venga lasciato molto spazio agli studenti per introdurre riferimenti personali, costruire livelli di conoscenza individuali e arrivare a una proposta finale autonoma. Quanto è importante questa libertà e come si relaziona con la struttura collettiva del laboratorio di progettazione? In altre parole, in che modo le traiettorie individuali si inseriscono in uno spazio di lavoro condiviso?

MC: È una domanda importante e complessa. Direi che essere un buon docente significa instaurare una conversazione reale con gli studenti. Bisogna guidarli, ma anche lasciar loro la possibilità di seguire il filo del proprio ragionamento. Non si tratta di stabilire cosa è giusto o sbagliato, ma di costruire un dialogo, spiegare la propria posizione e tornare sui temi della discussione nel tempo. In questo senso, non si ha libertà totale, perché non tutto è possibile. Anche nella scelta dei riferimenti, per esempio dei nomi di artisti o fotografi che chiediamo agli studenti di studiare, selezioniamo da un ambito molto preciso. Chiediamo agli studenti di scattare fotografie ispirandosi a un determinato autore, perché riteniamo che sia un modo produttivo per imparare a inquadrare e osservare. Dietro a queste scelte c’è sempre una lunga preparazione interna prima di ogni semestre. Lo stesso vale per la scelta del sito, che riflette un’attitudine specifica che intendiamo trasmettere. Organizziamo inoltre lezioni, brevi workshop e invitiamo ospiti esterni. In definitiva, creiamo un ambiente in cui gli studenti possano muoversi, orientarsi e trovare la propria posizione. Attraverso le discussioni settimanali, disegniamo e riflettiamo insieme e, in questo modo, gli studenti sviluppano i propri progetti e affinano il proprio modo di pensare, iniziando a comprendere le ragioni delle proprie scelte. Si tratta di un processo condiviso che coinvolge l’intero gruppo docente e dedichiamo molto tempo a riflettere sui progetti degli studenti. Ritengo che questa sia una responsabilità fondamentale di un buon team didattico: prendersi il tempo necessario per accompagnare gli studenti nel loro percorso e aiutarli a comprendere le ragioni delle proprie scelte. Alcuni trovano la propria strada più rapidamente e necessitano solo di un orientamento leggero, mentre altri hanno bisogno di più tempo. . Ogni studente è diverso per capacità, tempi e processi, e occorre lavorare su queste differenze. È un modo per comunicare e costruire fiducia. Alla fine, gli studenti dovrebbero essere in grado di sostenere il proprio progetto e di spiegarlo con chiarezza: è in quel momento che si allena davvero la predisposizione verso un pensiero critico, che rappresenta forse l’esito più interessante del laboratorio. Si tratta di trovare la propria voce. Amo molto il libro di bell hooks, Teaching Critical Thinking, perché affronta in modo profondo il tema dell’insegnamento, del rispondere e del resistere, e l’abbiamo trovato estremamente incisivo.

LA: Nel corso della nostra conversazione, ho notato che ricorrono spesso metafore legate alla voce e alla conversazione: dal dialogo tra gli studenti a quello all’interno del tuo gruppo di lavoro, fino al confronto con il sito e con la storia dell’architettura. In conclusione, sembra che il dialogo occupi una posizione centrale nel tuo approccio, sia nella didattica che nella pratica professionale. MC: Esattamente, sì, è proprio così.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

Luigiemanuele Amabile – Architect and PhD, research fellow of the project DT2 (UdR Università degli Studi di Napoli “Federico II”).

Maria Conen – Professor for Architecture & Housing, ETH Zürich; Conen Sigl Architects / Zurich.