Luigiemanuele Amabile in conversation with Tina Gregoric.

What does it mean to place material conditions at the origin of architectural education? In this interview, Tina Gregoric presents the design studio as a framework that resists standardisation and must be recalibrated each time in relation to the site, the topic and the scale. Within the condensed semesters at TU Wien, the studio adheres to precise rhythms of work and discussion, while remaining open to various pedagogical approaches, ranging from research trips to on-site experimentation and one-to-one prototyping. Gregoric’s approach transforms circularity and adaptive reuse from abstract concepts into a lived responsibility, grounded in direct engagement with space and matter. Gregoric rejects purely formal approaches to design in favour of a foundational education rooted in material knowledge, cultural awareness and ecological responsibility. Practice and teaching continuously inform one another, revealing how construction realities and institutional frameworks shape architectural action. Material typologies thus function not as formal classifications, but as operative tools for understanding contemporary conditions.

LA: In light of current debates on architectural pedagogy, could you outline how you conceive and structure a design studio – addressing organizational frameworks, pedagogical objectives, and the ensemble of methodological tools – and indicate which pressing epistemological or societal challenges you consider most urgent for studio-based learning today?

TG: Yeah – thank you for your question. I don’t believe in one universal strategy. I believe that every topic, theme, and site demands a tailor-made design studio. I have been teaching within this context of TU Wien for more than ten years – design studios – and I had to adapt my previous teaching methods to a large university. The context in Ljubljana or London, at the AA where I studied and briefly taught in both institutions, is very different. There, you build a vertical design studio where students stay with you for more than one semester. At TU Wien, each semester essentially starts from scratch. You present a topic, a brief, and from a large pool of students, you get a series of applications. Then, of course, you begin this journey. Over these ten years, we have dealt with significant differences in scale, topics, and contexts – and there is no single recipe.

Let’s start from the most recent, which was the most radical. Last year we became very involved in adaptive reuse. But last year we managed, through collaboration with external institutions, to define a bioregional design strategy, a design studio called Biofabrique Vienna, that was initiated by Wirtschaftsagentur Wien and Atelier LUMA with TU Wien as the executive partner. It was in collaboration with Luma Arles, which has become a kind of laboratory – showing, in one-size-fits-all recipe.

LA: Immersing students in one-to-one prototyping, as you did with Biofabrique Vienna, must alter the way they later navigate professional practice – in your observation, how does that lived material experience influence their ethical stance and decision-making once they leave the university?

TG: What students learned from that was: yes, you can have the agenda of circularity, bioregional approaches, and adaptive reuse – these are all familiar topics. But if you’re given the opportunity to physically inhabit and work within the very space you are proposing to transform – working directly on-site, sourcing and assembling materials on site – the entire process and outcome change dramatically. It completely shifts students’ mindset and sense of responsibility. Because they were inhabiting the space – the existing building they aimed to adapt into something else – they were living and working in the place they had to change. And it wasn’t something abstract. We used it throughout the entire semester. It wasn’t just about the brief or the methodology; it’s also about the location in which you can teach and the platform you offer students to work on. And especially at a large university like TU Wien – where we don’t have shared studio spaces for students – this was a major shift.

LA: Building on the Biofabrique case, how does that pedagogical experience compare with other studios you have directed, and which cross-cutting methodological principles or evaluative metrics remain constant across such diverse formats?

TG: What was not much different from all the other studios is that – as probably influenced by my Anglo-Saxon education 25 years ago at the AA in London – we always structure the design studio around mid-presentations and final presentations, with a strong emphasis on discourse and discussion. That is a key strategy. And of course, we also integrate a series of workshops, where in the same space – whether here or somewhere else – you truly work together as a team of students. What is unique to TU Wien is that it’s very intense but also a very short period of time because it’s only four months. More or less, with two weeks of holidays – either at Christmas or Easter – it totals 14 weeks. So we really plan each week strategically: what is the task, what is the expected output. It’s a weekly structured methodology in each of the design studios.

LA: The studios you have conducted have operated in very different contexts and conditions across Europe. How do you prepare students to engage with such heterogeneous rural or urban scenarios?

TG: Over the last ten years, we have explored a wide range of topics: healthcare architecture, nanotourism (a coined term describing a creative critique of the current environmental, social, and economic downsides of conventional tourism, as a participatory, locally oriented, bottom-up alternative, ndr), adaptive reuse in general. For over a decade now, we have also been rethinking the countryside. Naturally, the countryside north of Vienna is very different from the countryside in Istria on the Adriatic coast, or from the Alpine lakes in Austria. Understanding these contexts deeply – covering not only in spatial terms, but also regional, cultural, political, and economic specificities – is essential. We always combine projects with intensive excursions.

For example, when we started studying healthcare architecture, we focused on Denmark. After an intense research phase – probably around 2018 – we realized Denmark was already among the most progressive countries in healthcare design. Since healthcare architecture typically takes about ten years to fully develop, we wanted to study it in depth. These intensive excursions at the beginning of a design studio, where participants experience the typology or topic is experienced one-to-one, have been one of the decisive ways to engage with the project. For instance, during our healthcare studies, we visited Nord Architects’ Cancer Center, the Patients’ Hotel, and the Hospice – also by Nord Architects. These visits helped us understand strategies used in high-end hospitals, children’s hospitals, and smaller typologies. Ultimately, we worked on three specific sites in Copenhagen.

Another example involves redefining the pedagogy of a creative university – a concept for an Open Design Academy where art, design, and architecture would once again be taught cohesively, rather than as separate disciplines. Visiting Nantes to see Lacaton & Vassal’s architectural school and the Art Academy, a radical adaptive reuse project, was crucial. It allowed students to radically rethink what architecture or an Open Design Academy could be. Since we had sites in those two European countries, the students needed to understand the community and local context, how people were approaching those topics locally. We needed to spend time there, which we do that, we pair with local architects.

We also launched a series called Odd Lots, starting at the end of the COVID period. The theme of odd lots was inspired by Gordon Matta-Clark’s Fake Estates, where in the 1970s purchased these bizarre, oddly shaped, super small plots across New York – mostly in Queens – thought to be impossible to develop. We asked the question: given that we already build too much in Europe and don’t need more new buildings – since we already have plenty of empty structures already exist – are there opportunities in Vienna’s odd lots compared to other cities, despite efforts to densify urban centers? After all, Vienna is still expanding significantly with new housing, one of the few European capitals doing so extensively. We collaborated with various schools and another city. The first was Odd Lots: Vienna–Ljubljana, then moving to Vienna–Brussels, Vienna–Barcelona, and Vienna–Berlin. Through these collaborations, working with local schools, universities, and architects, we aimed to explore an alternative model of urban development – trying to curb the ongoing production of poorly planned urban masterplans that result in low-quality architecture. This is currently happening in Vienna’s new developments. After four years, we organized an intense symposium and an exhibition last year in Vienna, bringing together key protagonists from these cities so that urban planners, decision-makers, and the public could see that this isn’t just the architects’ perspective, but a broader conversation about treating cities and spaces.

LA: How do you navigate the tension between academic speculation and real-world implementation when engaging stakeholders?

TG: It’s about how the entire structure – how we initiate and approve new projects, how decision-making works – defines the urban condition. That’s why we invited the chief architect of Brussels, for example, to discuss their approach. Because the Brussels method, including their competition culture and planning tools, is completely different. My thesis was that, thanks to 15 or 20 years of competitions, institutional commitment, and leadership from figures like the chief architect, Belgium has created an entirely new architectural culture – not because Belgian architects are inherently more talented, but because young architects had opportunities to secure commissions and rethink the fundamental questions being asked.

LA: Considering the expanding hybridity of representational media in architectural research, to what extent do you prescribe or curate the instruments of inquiry – drawings, physical and digital models, computational simulations, narrative artefacts – and how do these choices shape the epistemic trajectory and critical outcomes of student projects?

TG: Yes, great question. We follow a specific template for research and output scale. For example, during starting excursions, like in Barcelona, students are given tasks to conduct targeted research while visiting architectural offices or touring important buildings. Each group might examine elements like entrances, fences, windows, and doors – key architectural features – and prepare detailed reports. Afterward, they present their findings to the class. This process uses structured templates to support group learning.

In contrast, their creative responses – such as in our New York trip – are entirely open in technique, tied to themes or sites we’ve explored related to Fake Estates and Odd Lots. They choose their medium freely, with the only requirement being a specific, precise model in a defined scale. But we don’t prescribe the material for the model. We don’t require a uniform type – what we focus on clarity and accuracy.

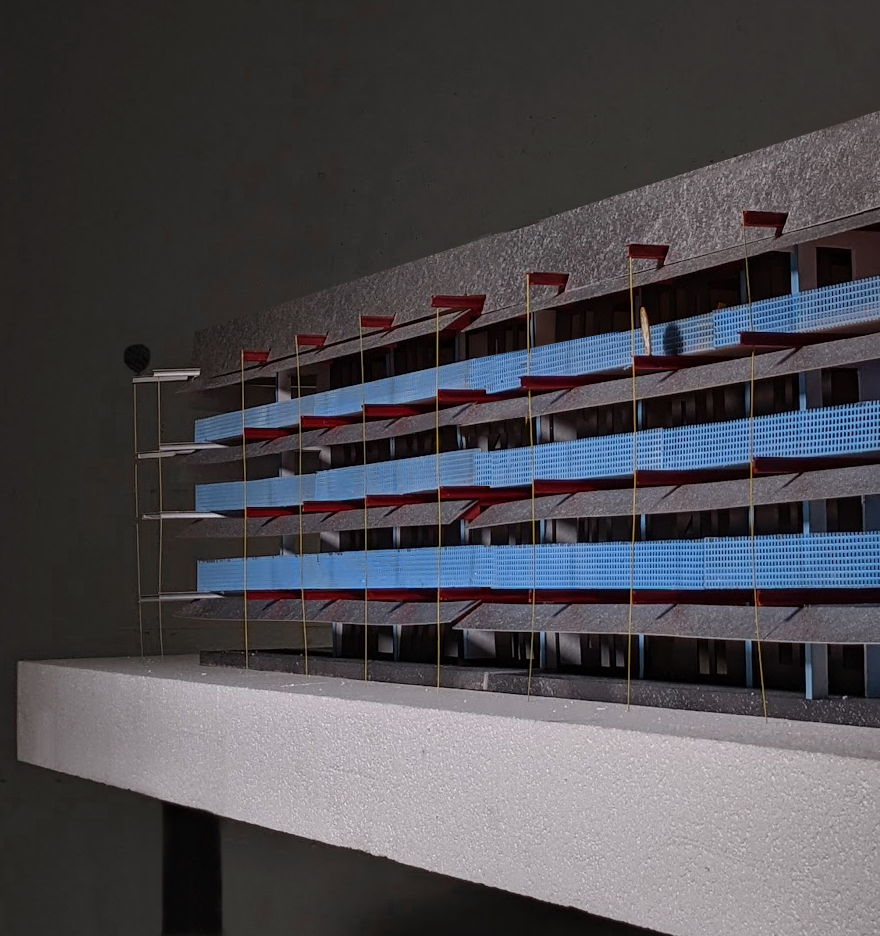

Similarly, for visualizations, we avoid hyper-realistic renderings. Instead, we favor collage or other representational methods that encourage critical thinking about materials. For instance, in the ‘Prefab’ studio, students select a material at the start of the semester – like rammed earth, CLT, or prefab concrete – and develop their project around its properties and techniques. Different materials require distinct design approaches.

While we give some freedom of expression, certain parts of the work – research, line drawings, and specific representational elements – are strictly defined. We maintain a balance, neither authoritarian nor entirely open. This flexibility sometimes surprises juries. We also organize all research in a structured format, including final materials, to streamline the publishing or exhibition process.

LA: That structured yet collaborative approach seems crucial. But given how quickly architectural practice evolves – with new tools, materials, and societal demands – how do you see the role of foundational teaching versus adaptability? Should curricula prioritize core principles, or is flexibility the new imperative?

TG: My own educational experience from the mid-90s to around 2002 aligns with this. During that period, digital architecture and parametric design began to take shape. By the time I visited the AA in 2000, these tools were already quite advanced. So, by the time it reached Die Angewandte a few years later, it was already outdated, which I found hard to accept because it focused solely on form. Even back in 2000 at the AA, we were sceptical, seeing it as a narrow focus on formal exploration. Testing these methods from various perspectives made us realize they are just tools. What troubled me most – having graduated in architecture and been involved in research and practice here in Ljubljana – was the idea of teaching architecture as merely formal experimentation. I believed that was fundamentally wrong in 2000. Now, 25 years on, we still question this, which seems strange to me. Especially since digital tools don’t account for material properties. You might start designing a shape resembling chewing gum, then search for a material to bend into that form, but that approach is flawed. Many materials simply cannot do that. Genuine parametric, contextual, and responsive design has existed since the 1960s, just not in a purely formal sense. Looking at Serge Chermayeff or Giancarlo De Carlo provides strong examples of what parametric architecture can be – beyond just shapes.

LA: You reject formalist digital design, yet computational tools are ubiquitous. Are there ways to teach design thinking that aligns with your material-first approach–for instance, through bio-inspired systems or fabrication constraints?

TG: I believe that teaching architecture only through formal experimentation is problematic, and this view has persisted for a long time. Instead, education should emphasize responsibility – understanding what already exists. This includes cultural and historical layers, like those in Italy, or environmental factors. The world isn’t unlimited. It’s only in the past decade or so that ecology has become a more mainstream concern. Of course, during the 1970s energy crisis, it was briefly a topic, but after oil prices fell, it was forgotten. Now, it’s finally taken seriously again. Ultimately, the aim of architectural education is to teach students to think critically. They must develop the ability to think conceptually while considering community, ecology, materials, and all contextual layers. It’s not just about creating a visual language that reflects themselves or their group. Architecture is a collective endeavour, and we’re only now beginning to truly grasp that.

LA: Given the enduring tension between generalist formation and early specialization within European architectural curricula, what is your position on balancing broad disciplinary literacy with domain-specific expertise, and how might curricula be recalibrated to prepare graduates for an increasingly complex professional and research landscape?

TG: I believe architecture is a very different field of study compared to, let’s say, mathematics, physics, or even art. In school, you engage with art, but you have almost no exposure to architecture before entering university. The first three years of architecture should focus solely on foundational knowledge – understanding resources, culture, and the history of architecture. You should ask: Why was something built in Athens differently than in Rome? You need to grasp that. Or why, in your own region or city, buildings were constructed in a certain way – who made those decisions and why? Of course, you must also learn the basic structural principles to build your general knowledge. You should also be introduced to urban and architectural history. However, our education – like many others – was biased. Modernism was glorified and not critically examined as it should have been. Postmodernism came and went, but honestly, that doesn’t matter much now. The key is understanding that styles aren’t the main point. What truly matters is understanding the conditions – at a specific time and place – that shaped a particular architectural response. The question is: What are the conditions today? What is the situation in a particular region, city, country, or even a small place? That’s what you need to respond to.

LA: What shifts would you advocate for in current architectural education to bridge the gap between material experimentation and the realities of contemporary construction practices?

TG: We shouldn’t teach students to be solely problem solvers. We should teach them to question the problem itself. If a student can’t challenge a competition brief – if they can’t come to me or my team and say, “What you are asking isn’t relevant because of this and this” – then we have failed to teach them how to think critically. And without that skill, wherever they specialize in their 50-year-long careers, they’ll become obedient, and they won’t change anything that truly matters. So yes – they need to be resilient. They have to be highly adaptable. But they also need a solid foundation, a base of knowledge, in order to be able to respond effectively. I genuinely appreciate the fluidity of architectural education in Europe – where you might start your bachelor’s degree in one place and finish your master’s in another. At TU Wien, many of our master’s students come from abroad. We’ve developed a strong bachelor’s program with my colleagues at the Institute of Architectural Design, so we expect students in their fourth year – the first year of master’s – to know the fundamentals. But of course, only about half have completed their bachelor’s here. The rest come from various backgrounds. And that’s wonderful – it fosters exchange and diversity. Erasmus programs are extraordinary. The only challenge is when students come from schools where the base isn’t strong – where they haven’t learned the necessary tools or architectural culture – they’re at a disadvantage. Architecture remains a relatively young discipline. And I believe you shouldn’t be entitled to design freely until you understand what you’re building on. Otherwise, it’s just ignorance. Students also need to be much better educated about material knowledge. They should be engaging more with design students and encouraging cross-disciplinary exchange. I’ve always admired the culture that existed in Italy in the 60s – at least from the outside – with figures like Bruno Munari, Andrea Branzi, and the Castiglioni brothers. The way they taught and discussed design didn’t matter whether it was a lamp or a city. Or think of Ernesto Nathan Rogers, writing from the spoon to the city. That’s the ideal I believe in. We should still teach students to design both the spoon and the city. Only by understanding all the scales – how one influences the others up and down – can you truly grasp what design entails. If we don’t foster this generalist perspective, then creating specialists might actually generate more problems. than solutions.

LA: Your description of alternating roles – from intensive studio mentoring to strategic advisory oversight – invites reflection on academic leadership models; could you elaborate on how these shifts in engagement influence learning cultures, staff development, and knowledge production within your institute?

TG: In our department, we have about ten people. Ten teachers plus me as the chair. This means that in some design studios, I’m one of two or three instructors, and I’m very involved. I see the students every other week, and we dive deeply into their projects. In other studios, my role is more like an advisor to the team – one or two of my staff prepare the brief, and I challenge them as they develop the methodology, references, and research structure. I only see the students’ work at the midterm and final. I switch between two very different roles, and both are important. But in some studios, when I’m more directly involved, I get much quicker feedback from the students – and they get it from me.

LA: Drawing on your dual engagement in professional practice and academic research, how do practice-based insights reciprocally inform your studio pedagogy, and conversely, in what ways does scholarly inquiry within the university milieu reshape the agendas and methodologies of your architectural practice?

TG: Yes – it’s obviously an exchange. I started teaching the same year we launched our practice. So I have always done both simultaneously. That means I have accumulated practical experience – from construction sites and legislation to detailing and building materials – that directly influences how I teach. For example, a few years ago, we won a competition for a new Science Center in Ljubljana. It was an international competition. We aimed to incorporate a circular approach in our design – low-tech, resource-saving, open-ended. But we faced serious challenges during the execution phase – not because of the design itself, but because of legislation. Public procurement makes it very difficult to use new materials that aren’t officially certified. We wanted to propose certain assemblies or techniques that lack standard certifications. The tender system actually works against circularity. And that was a huge lesson for me.

LA: When legislation stifles innovation, should studios train students to hack those systems–or to advocate for policy change? It seems you do this through a deep knowledge of materials and the technologies and techniques behind them.

TG: I brought my experience back to the studio. The students need to understand that sometimes, even with good intentions, the system itself can be the main obstacle. This is especially true regarding materiality. Our practice has always had a strong focus on materials. From our first building – because we came from the AA – we aimed to show that architecture isn’t just digital but about construction and real materials. Of course, theoretical architecture matters, but when it comes to building, it’s about brick, stone, concrete, or wood. If you don’t understand how these materials behave – if you haven’t worked with them – you shouldn’t be designing with them.

My ideal is every student visits a sawmill. For example, in 2016, we did the Slovenian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, emphasizing this. We built an inhabited structure inside the Arsenale – a curated library-home – and the goal was to create a space for people to linger, share knowledge, and experience open-source learning. We worked solely with untreated wood. The entire studio visited the sawmill. I had experience with that because my father owns a forest, but for most students, it was their first time. Understanding how wood is cut, treated, and its properties is vital, just like clay and bricks. Early in our careers, we experimented with brick and unfired clay, and we’ve incorporated that into our current work. Last year, someone asked me: «Why, as a professor of architectural typology, are you so focused on materials?” I responded simply: all architecture is material. Without rethinking typology through materials, your experiments – digital or physical – may miss future realities.

Beyond materials, we strongly value interdisciplinarity. We tell students they must collaborate with other creatives, artists, and material researchers; staying in a bubble isn’t enough. For example, in Ljubljana, we redesigned Slovenska Cesta to be nearly traffic-free, allowing only buses. We redefined the pavers used for sidewalks, collaborating with a company to develop those pavers and later, for the Science Center, to create a recycled version. That industry collaboration revealed how existing systems can be “hacked” to become more ecological. I also bring this approach to students because practice provides feedback – both on what worked and what didn’t. Revisit a housing project from five years ago and speak with its residents – that’s the real test.

LA: This process may be likened to a scenario where students are encouraged to engage with a continuous cycle of feedback that is enabled by practice. This entails a process of reflection and refinement, which involves revisiting and subsequently reintroducing elements into the studio environment.

TG: Again, we have built around a thousand affordable housing units. That scale provides a lot of feedback, which can be shared in teaching – not just about what your intentions were but also about the real outcomes. You learn what you missed, what failed, and what surprised you. That’s why I value collaborations like the one we now have with BC Architects. We invited them as long-term guest professors. They have gathered knowledge over 15 years of practice – something you can learn in school. You learn it by doing. What’s beautiful now is that in Europe, due to the urgency of the ecological agenda, people are much more willing to share what they’ve discovered. It’s no longer about hoarding knowledge. Designers and architects want to share methods, results, and even mistakes so others can build on them. Only then can we collectively create a real shift in architecture practice. And I have to say, what I enjoy most – when I have the rare opportunity – is working with first-year students or those in their very first semester. When you’re just starting your architectural journey, you are open to everything. You haven’t yet built resistance or preconceptions. If you set high standards from the start, foster a critical mindset, and give students real motivation, then you can do magic. But if from the beginning they are guided toward a banal, client-serving mindset – even with public clients – then you lose them. Another challenge we face is the quality of public clients in Europe. It’s not just commercial clients who lack culture or architectural awareness; public ones often do too. It’s extremely important how we define architects’ roles and responsibilities at the start of their education. We should motivate students not only to aspire to be the next Otto Wagner or an iconic figure – which is fine, of course – but also to understand the potential of working on the client side, whether in Vienna, a small town, or their own village. As a well-educated architect, you can achieve extraordinary things in those roles by asking the right questions and identifying the true potential of that land, community, or place. So yes – a lot of ambition, and not enough time. But for me, teaching is something I truly love. I get goosebumps just thinking about it because it’s a rare opportunity – where you can share and inspire more people than in practice alone. Your office might complete one great housing project, but with your students, you can influence the quality of many public spaces and neighbourhoods if they carry that mindset forward. That’s what I want to see – when our students succeed in creating something meaningful in their own contexts. That’s the biggest reward. That’s why I try to stay connected, remaining active both in practice and teaching, and bringing questions from the university back to the office and vice versa. It’s all connected.

______________________________________________________________________________________________

Tipologie Materiali

Luigiemanuele Amabile in conversazione con Tina Gregoric.

In che modo le condizioni fisiche e materiali dei manufatti possono essere alla base della formazione architettonica? In questa intervista, Tina Gregoric presenta il laboratorio di progettazione come un dispositivo che resiste alla standardizzazione e che deve essere ricalibrato ogni volta in relazione al luogo, al tema e alla scala. Nei semestri intensivi del TU Wien, il laboratorio segue ritmi precisi di lavoro e di discussione, rimanendo al tempo stesso aperto a diverse impostazioni pedagogiche che spaziano dalle ricerche sul campo alla sperimentazione in situ e alla realizzazione di prototipi in scala 1:1. L’approccio di Gregoric trasforma i concetti di circolarità e riutilizzo adattivo da astratti a consapevolezze situate, fondate su un confronto diretto con lo spazio e la materia. Gregoric rifiuta gli approcci puramente formalisti al progetto, rivendicando una formazione di base radicata nella conoscenza dei materiali, nella consapevolezza culturale e nella responsabilità ecologica. La pratica e la didattica si alimentano a vicenda, mostrando come le condizioni costruttive e i quadri istituzionali orientino l’azione architettonica. Le tipologie materiali assumono quindi il ruolo di strumenti operativi per comprendere le condizioni del presente piuttosto che di semplici classificazioni formali.

LA: Alla luce dei dibattiti attuali sull’insegnamento del progetto, come sono organizzati i laboratori di progettazione che conduci? Quali obiettivi didattici ti prefiggi e quali strumenti utilizzi? Quali urgenze epistemologiche o sociali ritieni siano oggi più pressanti da affrontare in un laboratorio?

TG: Non credo esista una strategia universale. Ogni tema, luogo e contesto richiede un laboratorio costruito su misura. Insegno alla TU Wien da più di dieci anni e, in questo arco di tempo, ho dovuto adattare i metodi che utilizzavo in precedenza alla scala e al funzionamento di una grande università. Il contesto di Lubiana o quello dell’Architectural Association di Londra, dove ho studiato e insegnato per un periodo, sono molto diversi. Lì gli studenti sono organizzati in laboratori verticali e li seguiamo per più di un semestre. Alla TU Wien, invece, ogni semestre rappresenta un nuovo inizio. Si presenta un tema, si prepara un brief e, da un bacino molto ampio di studenti, arrivano le candidature. Da quel momento inizia il vero percorso. In questi dieci anni abbiamo condotto esperienze su scale, temi e contesti diversi e non siamo in grado di definire un’unica ricetta. Partirei dall’esperienza più recente, che è stata anche la più radicale. Lo scorso anno ci siamo concentrati molto sul riuso adattivo. Grazie a una collaborazione con istituzioni esterne, siamo riusciti a definire una strategia di progetto bioregionale: un laboratorio chiamato Biofabrique Vienna, promosso da Wirtschaftsagentur Wien e Atelier LUMA, con TU Wien come partner operativo. Il progetto è stato sviluppato insieme a Luma Arles, che oggi è una vera e propria officina in grado di dimostrare che non esiste una soluzione applicabile a ogni evenienza.

LA: immergere gli studenti in prototipi in scala uno a uno, come nel caso di Biofabrique Vienna, influenza inevitabilmente il modo in cui poi si approcceranno alla progettazione nella pratica professionale. In base alla tua esperienza, in che modo approfondire gli aspetti materici incide sull’atteggiamento etico e sui processi decisionali una volta fuori dall’università?

TG: Quello che gli studenti hanno imparato è che, anche affrontando temi ormai ampiamente riconosciuti come la circolarità, le questioni legate ai materiali bioregionali e il riuso adattivo, se c’è la possibilità di abitare fisicamente e lavorare nello spazio che si sta progettando di trasformare, intervenendo direttamente sul posto e cercando e assemblando i materiali sul posto stesso, l’intero processo evolve in modo radicale. L’approccio didattico cambia completamente e il senso di responsabilità che gli studenti sviluppano è molto maggiore. Il fatto di occupare concretamente quello spazio da trasformare in qualcosa d’altro permetteva di aggiungere agli aspetti presi in considerazione dal progetto la vita delle persone che lo occupavano. Non parlo in astratto: abbiamo occupato lo spazio per tutto il semestre. Non si è trattato solo della costruzione di un brief o dell’impostazione metodologica, ma anche del luogo in cui si insegna e degli strumenti messi a disposizione degli studenti. In un ateneo grande come il TU Wien, dove non esistono spazi di laboratorio condivisi, questa modalità ha rappresentato un cambiamento profondo.

LA: Partendo dall’esperienza di Biofabrique, in che modo l’impostazione didattica si confronta con gli altri laboratori che hai diretto e quali principi metodologici o criteri di valutazione trasversali permangono in formati così diversi?

TG: Ciò che non è cambiato molto rispetto agli altri laboratori è che, probabilmente anche a causa dell’influenza della mia formazione anglosassone di venticinque anni fa presso l’Architectural Association di Londra, strutturo sempre il laboratorio attorno a critiche intermedie e finali, e attribuisco importanza fondamentale alla discussion collettiva. È una strategia fondamentale. A ciò si aggiungono una serie di workshop in cui, nello stesso spazio, qui o altrove, si lavora davvero insieme come gruppo di studenti. La specificità del TU Wien è che tutto avviene in modo molto intenso, ma in un arco di tempo estremamente breve, dato che il semestre dura solo quattro mesi. Togliendo due settimane di pausa tra le festività natalizie e la pausa primaverile, rimangono quattordici settimane effettive. Per questo motivo, pianifichiamo ogni settimana in modo preciso, indicando i compiti e gli esiti attesi. In ciascun laboratorio, adottiamo una metodologia scandita settimana per settimana.

LA: I laboratori che avete condotto si sono mossi in contesti e condizioni molto lontane fra loro e in tutta Europa. Come prepari gli studenti a confrontarsi con queste scenari rurali o urbani tanto eterogenei?

TG: Negli ultimi dieci anni abbiamo affrontato tantissimi temi: le architetture per la salute, il nanoturismo (un termine nato come critica agli effetti ambientali, sociali ed economici del turismo convenzionale e che propone un’alternativa partecipativa, locale e dal basso) e, naturalmente, il riuso adattivo. Da oltre un decennio stiamo anche ripensando il significato di lavorare in un paesaggio rurale. È evidente che la campagna a nord di Vienna non ha nulla a che vedere con quella dell’Istria sulla costa adriatica o con i laghi alpini in Austria. Comprendere a fondo questi contesti, nelle loro dimensioni spaziali, ma anche culturali, politiche, economiche e regionali, è fondamentale. Per questo motivo, affianchiamo sempre il progetto a viaggi di studio e sopralluoghi molto precisi. Per esempio, quando abbiamo iniziato a occuparci di architetture per la salute, abbiamo focalizzato la nostra attenzione sulla Danimarca. Dopo un’approfondita fase di ricerca, verso il 2018, abbiamo capito che la Danimarca era già uno dei paesi più all’avanguardia nel campo del progetto di strutture sanitarie. Considerato che il ciclo di costruzione di una architettura del genere richiede circa dieci anni, era evidente che avremmo dovuto approfondirla molto. Le escursioni all’inizio del laboratorio, che permettono agli studenti di vivere in prima persona un tipo o un tema, sono uno dei modi più incisivi per entrare nel progetto. Durante questo percorso, abbiamo visitato il Cancer Center di Nord Architects, il Patients’ Hotel e l’Hospice, tutti progettati dallo stesso studio. Queste visite ci hanno permesso di analizzare le strategie adottate negli ospedali di fascia alta, negli ospedali pediatrici e nelle strutture di piccole dimensioni. Alla fine, abbiamo lavorato su tre siti specifici a Copenaghen.

Un altro caso riguarda la ridefinizione delle modalità di insegnamento di un’università, un possibile modello di Open Design Academy in cui arte, design e architettura possano tornare a essere insegnate insieme e non come discipline separate. La visita alla scuola di architettura e all’Accademia d’arte di Lacaton & Vassal, un progetto radicale di riuso adattivo, è stata cruciale. Questo ha permesso agli studenti di ripensare in modo radicale il ruolo dell’architettura nella definizione di tale tipo. Poiché avevamo siti in quei due paesi europei, gli studenti hanno dovuto imparare ad ascoltare le esigenze della comunità e il contesto locale e il modo in cui questi temi venivano affrontati sul posto. Per questo motivo, abbiamo trascorso del tempo sul posto collaborando con architetti locali.

Abbiamo anche avviato una serie chiamata Odd Lots, nata verso la fine del periodo del COVID. Il tema trae ispirazione dai Fake Estates di Gordon Matta-Clark, che negli anni Settanta acquistò a New York, soprattutto nel Queens, piccoli lotti irregolari e apparentemente impossibili da sviluppare. Ci siamo quindi chiesti: dato che in Europa costruiamo già troppo e non abbiamo bisogno di nuovi edifici, visto che ci sono già moltissime strutture vuote, perché non cercare opportunità negli strani e irregolari lotti rintracciabili a Vienna? Nonostante i tentativi di densificare i centri urbani, Vienna continua a espandersi con nuovi quartieri residenziali, una condizione ormai rara tra le capitali europee. Abbiamo collaborato con diverse scuole e città, ogni volta diverse. Il primo ciclo ha visto la partecipazione di Vienna-Ljubljana, poi Vienna-Bruxelles, Vienna-Barcellona e Vienna-Berlino. Attraverso queste collaborazioni con scuole, università e architetti locali, abbiamo cercato di esplorare un modello alternativo di sviluppo urbano, provando a contrastare la costante produzione di masterplan scarsamente pianificati che generano architettura di bassa qualità. È ciò che sta accadendo oggi nelle nuove espansioni di Vienna. Dopo quattro anni, abbiamo organizzato un simposio e una mostra a Vienna, riunendo le figure chiave di tutte queste città, affinché urbanisti, decisori pubblici e cittadini potessero rendersi conto che non si trattava solo della prospettiva degli architetti, ma di una conversazione più ampia sul modo in cui trattiamo le città e gli spazi.

LA: Come ti muovi tra la dimensione più esplorativa della progettazione accademica e le condizioni reali di attuazione quando il lavoro del laboratorio si intreccia con interlocutori e contesti concreti?

TG: La questione riguarda il modo in cui l’intera struttura gestionale, ovvero il modo in cui attiviamo e approviamo i nuovi progetti e il funzionamento dei processi decisionali, determina la condizione urbana. Per questo motivo, abbiamo invitato, per esempio, il chief architect di Bruxelles a discutere del loro approccio. Il metodo di Bruxelles, che spazia dalla cultura dei concorsi agli strumenti di pianificazione, è molto specifico. In quindici o venti anni di concorsi, uniti a un impegno istituzionale costante e alla guida di figure come il chief architect, il Belgio è riuscito a costruire una cultura architettonica completamente nuova. Non perché gli architetti belgi siano più talentuosi di altri, ma perché le generazioni più giovani hanno avuto l’opportunità di ottenere incarichi e di ripensare in modo approfondito le domande da cui partire.

LA: Considerata la crescente ibridazione dei mezzi di rappresentazione nella ricerca architettonica, in che misura definisci o selezioni gli strumenti dell’indagine – disegni, modelli fisici e digitali, simulazioni computazionali, artefatti narrativi – e in che modo queste scelte orientano la traiettoria epistemica e gli esiti critici dei progetti degli studenti?

TG: Impostiamo un format preciso per gli elaborati di ricerca e per i disegni di progetto. Durante i viaggi di studio, gli studenti vengono suddivisi in gruppi di indagine mirati e hanno l’opportunità di imparare dagli studi di architettura e di visitare edifici significativi. Ogni gruppo analizza elementi quali ingressi, recinzioni, finestre e porte, dettagli fondamentali del lessico architettonico, e prepara una documentazione approfondita. Solo dopo, presentano il loro lavoro al resto del gruppo. Si tratta di un processo scandito dall’utilizzo di modelli di riferimento che sostengono l’apprendimento collettivo. Le loro risposte progettuali, invece, sono completamente aperte a tecniche diverse, a condizione che siano legate ai temi esplorati nelle Fake Estates e negli Odd Lots. Gli studenti scelgono liberamente il proprio mezzo espressivo, con l’unico vincolo di realizzare un modello preciso a una scala definita. Non imponiamo un tipo di materiale né un metodo specifico: ciò che conta è la chiarezza e l’accuratezza. Lo stesso vale per le visualizzazioni. Evitiamo i rendering iperrealistici e preferiamo i collage o altre modalità di rappresentazione che incoraggino uno sguardo critico sulla materia. Nel laboratorio Prefab, per esempio, ogni studente sceglie un materiale all’inizio del semestre – terra battuta, legno lamellare incrociato (CLT) o calcestruzzo prefabbricato – e sviluppa l’intero progetto a partire dalle sue proprietà e dalle tecniche di lavorazione. Materiali differenti implicano approcci progettuali diversi. Pur concedendo una certa libertà espressiva, alcune parti del lavoro, come la fase di ricerca, i disegni a linee e altri elementi specifici di rappresentazione, sono definite in modo rigoroso. Cerchiamo di mantenere un equilibrio tra precisione e apertura alle possibilità dei singoli. A volte, questa elasticità sorprende i critici invitati. L’intero corpus di ricerche è organizzato in un formato strutturato, compresi gli elaborati finali, così da rendere più agevole il processo di pubblicazione e di allestimento.

LA: Trovare un punto tra organizzazione del Corso e l’autodeterminazione degli studenti è fondamentale. Ma, considerando la rapidità con cui l’architettura sta cambiando – nuovi strumenti, tecnologie, esigenze sociali e culturali – come immagini oggi il rapporto tra gli insegnamenti di base e la capacità di adattamento alle contingenze? I curricula dovrebbero privilegiare la trasmissione dei principi fondativi della disciplina o la flessibilità è diventata l’imperativo dominante?

TG: La mia formazione, dalla metà degli anni Novanta fino ai primi anni Duemila, si inserisce esattamente in questo periodo di transizione. In quel periodo, l’architettura digitale e il design parametrico stavano iniziando a emergere. Quando nel 2000 sono arrivata all’AA, l’uso di questi strumenti era già molto avanzato. Così, quando qualche anno dopo questo approccio è arrivato alla Die Angewandte, quella fase era già superata. Fu difficile accettare il fatto di concentrarsi esclusivamente sul raggiungimento di una forma. Anche all’AA, nel 2000, eravamo piuttosto scettici, perché lo consideravamo un esercizio troppo limitato alla dimensione formale. Mettere alla prova questi metodi da angolazioni diverse ci ha fatto capire che si trattava semplicemente di strumenti. Dopo essermi laureata in architettura e aver cominciato a lavorare tra ricerca e professione a Lubiana, ciò che mi preoccupava di più era l’idea di insegnare l’architettura come pura sperimentazione formale. Già allora mi sembrava un errore. Oggi, a venticinque anni di distanza, ci ritroviamo a interrogarci sulle stesse cose e trovo che sia una strana ricorrenza. Questo soprattutto perché gli strumenti digitali non integrano le proprietà dei materiali. A volte si disegna una forma che sembra gomma da masticare e poi si cerca un materiale che possa essere piegato in quel modo. Questo approccio è fallace. Semplicemente, molti materiali non possono farlo. Il vero design parametrico, contestuale e reattivo esiste dagli anni Sessanta, ma non si presentava come un esercizio formale. Serge Chermayeff o Giancarlo De Carlo mostrano in modo molto eloquente cosa possa essere un’architettura parametrica, al di là delle forme.

LA: Rifiuti un approccio digitale formalista, eppure gli strumenti computazionali sono ormai onnipresenti. Esistono dei metodi per insegnare il progetto in linea con la tua idea di partire dalla materia, per esempio attraverso sistemi bio-ispirati o vincoli legati ai processi di fabbricazione?

TG: Sono ancora convinta che insegnare l’architettura come pura sperimentazione formale sia un approccio problematico e questa convinzione mi accompagna da tempo. L’educazione dovrebbe mettere al centro il senso di responsabilità, a partire dalla comprensione di ciò che già esiste, dalle stratificazioni culturali e storiche, come nel caso dell’Italia, fino alle condizioni ambientali. Le risorse del mondo non sono infinite. Solo nell’ultimo decennio l’ecologia è diventata un tema diffuso. Negli anni ‘70, durante la crisi energetica, se ne parlò per un breve periodo, ma poi, con il calo dei prezzi del petrolio, il tema fu accantonato. Oggi, finalmente, è tornata a essere una questione presa sul serio. In definitiva, l’obiettivo della formazione in architettura è insegnare agli studenti a pensare in modo critico. Devono sviluppare una capacità concettuale che tenga insieme aspetti sociali, ecologici, materiali e le stratificazioni culturali che emergono dai contesti che affrontano. Non si tratta di costruire un linguaggio visivo che rifletta soltanto sé stessi o le proprie idee. L’architettura è un impegno collettivo e forse solo ora stiamo iniziando a comprenderlo davvero.

LA: Considerata la relazione ancora molto presente nei percorsi europei di formazione tra un approccio generalista e una specializzazione disciplinare, qual è la tua posizione riguardo al bilanciamento tra un modello di formazione ampio e la necessità di sviluppare competenze mirate? In che modo i curricula potrebbero essere ripensati per preparare i laureati a un panorama professionale e di ricerca sempre più complesso?

TG: Credo che l’architettura sia un ambito di studio molto diverso dalle scienze, come la matematica o la fisica, o persino dall’arte. A scuola si entra in contatto con l’arte, ma quasi mai con l’architettura prima dell’università. Per questo motivo, i primi tre anni dovrebbero concentrarsi esclusivamente sulle basi: la comprensione delle risorse, della cultura e della storia dell’architettura. Bisogna chiedersi perché ad Atene si costruiva in un modo e a Roma in un altro. Oppure perché gli edifici nella tua regione o nella tua città sono stati costruiti secondo determinate logiche e chi ha preso quelle decisioni e per quali ragioni. Naturalmente, è necessario anche apprendere i principi strutturali fondamentali per sviluppare un sapere generale e confrontarsi con la storia urbana e architettonica. Tuttavia, la nostra formazione, come molte altre, è parziale. Il modernismo veniva celebrato e raramente messo in discussione. Il postmodernismo è arrivato e poi è svanito, ma oggi, a dire il vero, non ha più alcuna importanza. La questione non è lo stile. Ciò che importa davvero è comprendere le condizioni che, in un determinato momento e in un luogo specifico, hanno prodotto una determinata risposta architettonica. La domanda allora è: quali sono le condizioni attuali? Quale situazione caratterizza una regione, una città, un paese o persino un luogo molto piccolo? È a questo che dovremmo imparare a rispondere.

LA: Quali trasformazioni ritieni siano necessarie nell’insegnamento del progetto per colmare il divario tra la necessità di sperimentazione e le condizioni concrete dell’industria delle costruzioni odierna?

TG: Dovremmo formare degli studenti che non siano meri risolutori di problemi. Dovremmo insegnare loro a mettere in discussione i problemi: se uno studente non riesce a interrogare le questioni affrontate da un brief di concorso e non è in grado di trasmetterci l’inadeguatezza di alcune delle nostre richieste, allora significa che non gli abbiamo trasmesso strumenti sufficienti a formare un pensiero critico autentico. Se non possiedono questa capacità, qualunque specializzazione sceglieranno nei cinquant’anni della loro futura carriera, finiranno per diventare soltanto dei dipendenti obbedienti, incapaci di incidere dove conta davvero. È necessario che siano resilienti e sappiano adattarsi. Ma è necessaria anche una solida base di conoscenze, un fondamento chiaro, per poter rispondere in modo consapevole. La flessibilità della formazione degli architetti in Europa va protetta. Qui è possibile iniziare il percorso di laurea triennale in un luogo e concludere il master in un altro. Alla TU Wien, molti dei nostri studenti magistrali provengono dall’estero. Insieme ai colleghi dell’Institute of Architectural Design, abbiamo costruito un corso di laurea triennale molto attraente, per cui ci aspettiamo che, al primo anno della magistrale, gli studenti conoscano già le basi. Naturalmente, solo la metà di loro ha completato qui il percorso di laurea triennale; gli altri provengono da percorsi molto diversi. Questo è un valore aggiunto, perché genera scambio e diversità. Il programma Erasmus dà sempre risultati straordinari. L’unica difficoltà si verifica quando arrivano studenti che provengono da scuole in cui le basi non sono solide e in cui non hanno acquisito gli strumenti e la cultura architettonica necessari. In questi casi, partono svantaggiati. L’architettura è una disciplina relativamente giovane e non si può pretendere di progettare liberamente senza aver compreso la materia su cui si sta costruendo. In caso contrario, si tratta di semplice ignoranza. Gli studenti dovrebbero anche avere una conoscenza più approfondita dei materiali. Sarebbe utile che lavorassero di più a stretto contatto con gli studenti di design, favorendo un vero scambio interdisciplinare. Ho sempre ammirato, almeno da fuori, la cultura italiana degli anni Sessanta, con figure come Bruno Munari, Andrea Branzi e i fratelli Castiglioni. Il modo in cui insegnavano e discutevano di progetto non faceva distinzione tra una lampada e una città. Pensiamo, per esempio, a Ernesto Nathan Rogers che scriveva: «Dal cucchiaio alla città». È un ideale in cui credo profondamente. Dovremmo continuare a insegnare agli studenti a progettare sia il cucchiaio sia la città. Solo comprendendo tutte le scale e il modo in cui ciascuna influisce sulle altre, dal piccolo al grande e viceversa, si può davvero capire cosa significhi progettare. Se non coltiviamo questa visione d’insieme, rischiamo che la formazione di specialisti generi più problemi che soluzioni.

LA: La dinamica che alterna momenti di partecipazione diretta nel laboratorio a fasi di supervisione più strategica solleva questioni sul modello di leadership accademica. In che modo queste diverse modalità di coinvolgimento incidono sulle culture dell’apprendimento, sulla crescita del personale docente e sui processi di produzione della conoscenza all’interno dell’istituto?

TG: In istituto siamo in dieci. Ci sono dieci docenti, più me che coordino la struttura. Ciò significa che in alcuni laboratori di progettazione sono una delle due o tre persone che guidano il corso e il mio coinvolgimento è molto diretto. Vedo gli studenti a settimane alterne e insieme approfondiamo determinati aspetti dei loro lavori. C’è un dialogo continuo. In altri casi, invece, assumo il ruolo di advisor: uno o due colleghi preparano il syllabus e io cerco di affinare la metodologia proposta, i riferimenti scelti e la strutturazione della fase di ricerca. In questi casi, vedo i progetti degli studenti solo a metà e alla fine del loro percorso. Mi muovo tra due funzioni molto diverse, ma entrambe necessarie. Quando però sono più presente, lo scambio con gli studenti è immediato e la rapidità con cui circolano i feedback diventa un elemento fondamentale per l’apprendimento.

LA: Considerando il costante intreccio tra pratica professionale e attività di ricerca accademica, in che modo le conoscenze maturate nei progetti in cantiere orientano la didattica di laboratorio? E, al contrario, come le forme di indagine sviluppate in ambito universitario contribuiscono a ridefinire agende e metodologie della pratica architettonica?

TG: Certo, si tratta evidentemente di uno scambio continuo. La mia attività didattica è iniziata nello stesso anno in cui è stato avviato lo studio professionale e le due dimensioni si sono sempre sviluppate in parallelo. Nel tempo si è accumulata un’esperienza pratica che spazia dai cantieri alla legislazione, dal dettaglio costruttivo ai materiali, e tutto ciò ha un impatto diretto sulla didattica. Qualche anno fa, per esempio, abbiamo vinto un concorso internazionale per la realizzazione di un nuovo Science Center a Lubiana. L’impostazione progettuale mirava a un approccio circolare, low-tech, attento alle risorse e aperto alle possibilità di evoluzione, ma durante la fase esecutiva sono emerse difficoltà sostanziali non legate al progetto in sé, bensì al quadro normativo. Nei lavori pubblici è molto difficile introdurre materiali che non abbiano ancora una certificazione ufficiale. Nel progetto erano stati proposti assemblaggi e tecniche che non rientravano negli standard previsti e il sistema degli appalti si è rivelato, di fatto, contrario ai principi della circolarità. È stata una lezione significativa.

LA: Quando la normativa diventa un freno all’innovazione, i laboratori di progettazione dovrebbero spingere gli studenti a «forzare» quei sistemi o a promuovere un cambiamento delle politiche? Sembra che nei vostri corsi ciò avvenga anche attraverso una conoscenza approfondita dei materiali, delle tecnologie e delle tecniche costruttive.

TG: Ho riportato questa esperienza direttamente nel laboratorio. Gli studenti devono comprendere che, talvolta, anche con le migliori intenzioni, è il sistema stesso a costituire l’ostacolo principale, soprattutto quando si tratta di materiali. Nella pratica progettuale, l’attenzione alla materia è sempre stata centrale. Fin dal nostro primo edificio, anche sotto l’influenza dell’AA, abbiamo cercato di mostrare che l’architettura non è soltanto digitale, ma riguarda la costruzione e i materiali reali. La speculazione teorica progettuale ha certamente un valore, ma quando si costruisce bisogna fare i conti con i materiali: mattoni, pietra, calcestruzzo o legno. Se non si conoscono le caratteristiche di questi materiali e non si è mai lavorato con essi, non si dovrebbe nemmeno pensare di progettare con essi.

Il mio ideale sarebbe che ogni studente visitasse una segheria. Nel 2016, per esempio, abbiamo voluto insistere su questo aspetto per il Padiglione sloveno alla Biennale di Venezia. All’interno dell’Arsenale abbiamo realizzato una piccola architettura abitabile, una biblioteca-casa concepita come luogo in cui soffermarsi, condividere conoscenze ed esperire un apprendimento aperto. Si è lavorato esclusivamente con legno non trattato. Tutto il laboratorio ha visitato la segheria. Io avevo già dimestichezza con quel mondo, perché mio padre possiede un terreno ricco di alberi, ma per la maggior parte degli studenti si trattava di una prima esperienza. Comprendere come il legno viene tagliato, lavorato e quali siano le sue proprietà è essenziale, così come lo è per l’argilla o il mattone. All’inizio della nostra attività professionale, abbiamo sperimentato con i mattoni e l’argilla cruda e questo approccio ha influenzato il nostro lavoro attuale. L’anno scorso qualcuno mi ha chiesto: «Perché, in qualità di docente di tipologie architettoniche, ti concentri così tanto sui materiali?» La mia risposta è stata semplice: tutta l’architettura è materia. Se non si ripensa la tipologia attraverso la materia, le sperimentazioni, siano esse digitali o fisiche, rischiano di non tenere conto delle condizioni future.

Oltre all’attenzione ai materiali, attribuiamo grande importanza all’interdisciplinarità. Spieghiamo agli studenti che devono collaborare con altre figure creative, come gli artisti e i ricercatori dei materiali, perché non è sufficiente restare chiusi in una bolla. A Lubiana, per esempio, abbiamo riprogettato la strada Slovenska Cesta, rendendola quasi interamente pedonale e riservando l’accesso ai soli autobus. Le lastre per i marciapiedi sono state progettate in collaborazione con un’azienda che ci ha poi supportato nella realizzazione di una versione riciclata destinata al Science Center. Collaborare con le industrie ha dimostrato che è possibile aggirare i sistemi esistenti per ottenere risultati più ecologici. Questo approccio lo trasferiamo anche agli studenti, perché la pratica fornisce un riscontro costante su ciò che ha funzionato e su ciò che non ha funzionato. Tornare dopo cinque anni in un edificio residenziale e parlare con chi lo abita rappresenta, in definitiva, la verifica più autentica.

LA: Nel processo che descrivi, agli studenti viene richiesto di confrontarsi con un ciclo continuo di feedback attivato dalla pratica. Ciò implica un percorso di riflessione e affinamento che prevede il ritorno sui progetti e la successiva reintroduzione di elementi nell’ambiente di laboratorio.

TG: Un altro esempio: abbiamo realizzato circa mille alloggi a prezzi accessibili. Una scala simile genera una quantità significativa di riscontri che possono essere condivisi nell’insegnamento, non solo rispetto alle intenzioni iniziali, ma anche rispetto agli esiti reali. Si impara ciò che è sfuggito, ciò che non ha funzionato e ciò che ha sorpreso. Per questo motivo, ritengo che collaborazioni come quella che abbiamo oggi con BC Architects siano preziose. Li abbiamo invitati a ricoprire il ruolo di docenti. Sono portatori di un sapere costruito in quindici anni di pratica, un sapere che non viene insegnato a scuola. Lo si apprende facendo. Ciò che apprezzo particolarmente, nel contesto europeo attuale, è che l’urgenza dell’agenda ecologica rende le persone molto più propense a condividere le conoscenze acquisite. Non si tratta più di custodire ciò che si scopre. Progettisti e architetti desiderano condividere metodi, risultati e persino errori, affinché altri possano trarne vantaggio. Solo così è possibile generare un cambiamento reale nella pratica architettonica. Devo dire che, quando ne ho l’occasione, ciò che apprezzo di più è lavorare con gli studenti del primo anno e del primo semestre. All’inizio del percorso di architettura si è aperti a tutto, senza resistenze o preconcetti. Se si fissano standard elevati fin dall’inizio, si coltiva un atteggiamento critico e si offre una motivazione autentica, si possono ottenere risultati davvero sorprendenti. Se, invece, fin dalle prime fasi, si indirizzano gli studenti verso una mentalità banale, orientata esclusivamente alla soddisfazione del cliente, anche quando si tratta di un cliente pubblico, allora si rischia di perderli. Un’altra questione riguarda la qualità dei committenti pubblici in Europa. Non solo la committenza commerciale spesso manca di cultura e consapevolezza architettonica, ma anche quella pubblica non fa eccezione. Per questo motivo, è fondamentale definire le responsabilità e il ruolo degli architetti fin dall’inizio del loro percorso formativo. Bisognerebbe motivarli non solo a diventare il prossimo Otto Wagner o una figura iconica, un’aspirazione legittima, naturalmente, ma anche a riconoscere il valore di lavorare per la committenza, sia a Vienna, sia in una piccola città, sia nel proprio Paese. Un architetto con una solida formazione può ottenere risultati straordinari anche in questi ruoli, se è in grado di porre le domande giuste e di individuare il potenziale di un luogo, di una comunità o di un territorio. Sì, c’è molta ambizione e poco tempo. Ma l’insegnamento è qualcosa a cui dedico molta passione. Pensare a questo mi emoziona, perché si tratta di un’occasione rara che mi permette di condividere e ispirare un numero di persone molto maggiore rispetto a quanto potrei fare con la sola pratica professionale. Uno studio può realizzare un grande edificio residenziale, ma è attraverso gli studenti che è possibile influenzare la qualità di molti spazi pubblici e quartieri, a condizione che si mantenga questa mentalità. Questo è ciò che desidero: vedere gli studenti creare qualcosa di significativo nei contesti in cui andranno a operare. È la soddisfazione più grande. Per questo motivo, cerco di rimanere in contatto con entrambe le dimensioni, lavorando sia nel campo della professione che in quello dell’insegnamento e portando le domande dell’università nel mio studio, così come riporto in università ciò che emerge dalla pratica. Tutto è collegato.

______________________________________________________________________________________________

Luigiemanuele Amabile – Architect and PhD, research fellow of the project DT2 (UdR Università degli Studi di Napoli “Federico II”).

Tina Gregoric – Professor of Architecture and Head of the Department for Building Theory and Design (Gebäudelehre und Entwerfen), Institute of Architecture and Design at TU Wien; architect and cofounder of the architectural practice Dekleva Gregoric architects (co-founded with Aljosa Dekleva in 2003)